| Also in this issue: In Appreciation: Donald Neff, 1930-2015 |

By Basem L. Ra’ad

At last year’s Toronto Palestinian Film Festival, I attended a session entitled “Jerusalem, We Are Here,” described as an interactive tour of 1948 West Jerusalem. It was designed by a Canadian-Israeli academic specifically as a virtual excursion into the Katamon and Baqʿa neighborhoods, inhabited by Christian and Muslim Palestinian families before the Nakba — in English, the Catastrophe.

Little did I anticipate the painful memories this session would bring. The tour starts in Katamon at an intersection that led up to the Semiramis Hotel. The hotel was blown up by the Haganah on the night of 5-6 January 1948, killing 25 civilians, and was followed by other attacks intended to vacate non-Jewish citizens from the western part of the city. Not far from the Semiramis is the house of my grandparents, a three-story building made of stone that my grandfather, a stone mason, had designed for the future growth of the family. It still stands today. I visited the location recently and found it occupied by Israelis, who never compensated my grandparents or even asked permission. My parents and their children lived nearby in Baqʿa. Then on April 9 the Irgun and Stern gangs executed the massacre at Deir Yassin which, combined with other Zionist plans for depopulation (the last Plan D or Dalet), led to the complete exodus of Palestinians from West Jerusalem and surrounding villages, as well as hundreds of towns and villages in Palestine. Our family and almost 30,000 West Jerusalem Palestinians, plus 40,000 from nearby villages, adding up to more than 726,000 from throughout Palestine (close to 900,000 according to other U.N. estimates) were forced into refugee status and not allowed to return to their homes.

The true story of West Jerusalem is far from what Zionist propaganda portrays to justify the expulsion of its Palestinian inhabitants: an “Arab attack” against which the Jews held bravely, rich Palestinians escaping on the first sign of violence, then being overwhelmed by Jewish immigrants whom the Israelis were forced to let stay in vacated Arab houses—or other similar tales.

In 1995, I made a “return” to Palestine by virtue of a foreign passport that allowed me to enter on a three-month visa. I was obliged to leave at the end of each three-month period and to rent accommodations. It was not always easy to get the usual three months, and I wasn’t allowed to renew my stay internally, though the Ministry of Interior gives renewals to other holders of foreign passports for those not of Palestinian origin. I faced restrictions and received none of the privileges accorded to Jews, born elsewhere, who wished or were recruited to come to the country of my birth. By this time, my grandparents and my parents had died and were buried in Jordan. East Jerusalem has been occupied since 1967, and the whole of geographic Palestine controlled by Israel.

Before crossing, I searched the papers kept by my brother in Jordan and discovered two documents: one related to a parcel of land my parents had purchased in the early 1940s, and the other a deed to a piece of land on the way to Beth Lahm/Bethlehem my father acquired in 1954 (in “the West Bank,” then under Jordanian rule), perhaps thinking of it as a substitute for the loss in 1948. In searching for the first parcel, I was told a request for information has to go to a Tel Aviv office, though I’m pretty sure it would be found to be classified under the Absentees’ Property Law and thus already expropriated by the Israelis.

I then started looking for the second parcel. No one seemed to know about it; the Israeli municipal office said it did not exist. Months passed when by accident I raised the subject with a colleague who told me she heard about that area and that I should check with an old man who lives near New Gate. The man indeed had maps and documents for the parcels in that development. He told me that after 1967 he lost contact with some landowners who lived on the other side of the Jordan river, that the whole hillside was expropriated by the Israeli government in 1970 to build the colony of Gilo. He showed me letters that he as a representative had written to various governments, to the U.N., to the Pope, to any organization he thought could help, to no avail.

To recall such events highlights a small part of the enormity of the Palestinian Nakba. Depopulating Palestinians from West Jerusalem was part of the process of destruction and ethnic cleansing of scores of cities and towns and hundreds of villages throughout the whole of Palestine, documented in Walid Khalidi’s All That Remains and Ilan Pappe’s Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. The Arab countries were half-hearted in their interference on May 15, with ill-equipped armies and foreign-influenced governments; the Palestinians were unprepared and poorly mobilized to deal with a well-planned Zionist invasion, their resources and much of the leadership having been decimated by the British in the 1936-39 uprising. The Zionist plan has continued to operate and expand until today, pursuing its objective for control of all of Palestine, in spite of Israel having agreed to the U.N. partition plan leading to two states and to the return of Palestinian refugees as a condition for Israel’s acceptance as a member of the U.N.

What happened in West Jerusalem in 1948 is today sidelined by the attention given to occupied East Jerusalem, with the issues shifted in focus to make it appear as if the “dispute” is now only about the “West Bank” and “East Jerusalem.” To begin with West Jerusalem is to emphasize that any eventual solution must account for it as part of the refugee issue, which also includes other cities like Yafa and Haifa and hundreds of villages throughout the country, either destroyed (as with most of them), replaced by colonies, or kept intact as in the old homes now inhabited by Israelis without regard for the original owners (in places like ‘Ein Hawd/Ein Hod and ‘Ein Karem).

This essay analyses the claim Israel used for taking Palestinian land, and details Israel’s Judaizing actions within the city and outside in the expanded municipal boundaries where several Jewish colonies have been built. It discusses the most blatant “laws” enacted by Israel to provide legal cover for its takeover of land and properties and its measures to control the city’s demography by applying discriminatory regulations on residency.

The Zionist Claim System

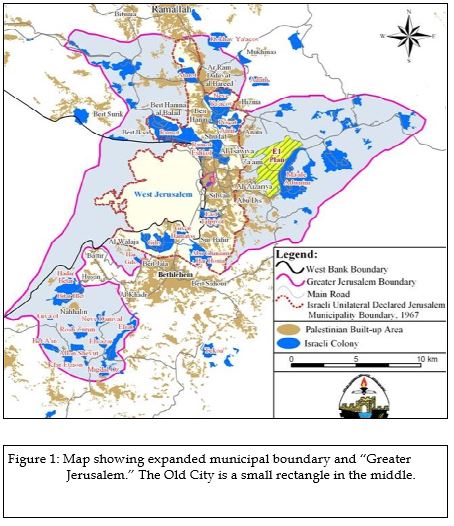

When considering historical Jerusalem, we think of the small area now called the Old City, contained within the Ottoman walls completed in 1541. It is less than one square kilometer, compared to the city’s current self-declared Israeli boundaries, which encompass 123 square kilometers. In the map (Figure 1) the Old City is the barely noticeable rectangle in the middle. Before June 1967, Jordanian-controlled East Jerusalem, along with suburbs outside the wall, measured only 6 square kilometers, while West Jerusalem covered 32 square kilometers. The boundaries that existed until 1967 were the result of the 1949 Armistice Agreement. The “green line” then violated the stipulation in the U.N. partition resolution that Jerusalem and surrounding areas be designated as a “corpus separatum.” The city’s internationalization as a kind of Vatican, affirmed in later resolutions, still informs the special status of various consulates, and points to the specific impropriety of the recent U.S. recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.

The Zionist claim system, which was developed and adapted over more than a hundred years, was preceded for centuries by a somewhat similar Western claim system. The identification with biblical narratives was useful in providing a religious rationale for colonial and racial theories, starting with the discovery of the New World and expanding across the world starting in the sixteenth century. Accounts like Exodus and “the Conquest of Canaan” drove colonial projects in North America, Australia and South Africa. Colonists in what became the U.S. and Canada transferred biblical typology to construct a myth of exceptionalism—as God’s Chosen People entitled to conquer, dispossess, and exterminate millions of indigenous inhabitants. Later in the 19th century emerged a movement called “sacred geography” as a literal tracing in the “Holy Land” to salvage old religious understanding against the discoveries that undermined biblical historicity. It produced hundreds of travel accounts of Palestine and semi-scholarly works of “biblical archaeology” that prepared the ground for Zionism. This antiquated model for dispossession is now alive in “the Holy Land,” and has revived similar entitlements.

Fixating on Old Testament narratives and exaggerated connections, Zionist claims about Palestine go something like this: followers of Judaism about 2,000 years ago are the same as Jews today, which gives today’s Jews the right to occupy Palestinian land because of promises inserted in the Bible, which they interpret as given to them by “God.” Hebrew is seen as a very ancient language that goes back to the presumed time of Moses and before him Abraham, although it did not exist in those periods but was a later appropriation of other languages and scripts such as Phoenician and Aramaic.

Zionist arguments encompass a whole complex of assumptions and fabrications which, to be realized, have had to take over aspects of continuity available only in the people who lived on the land, the Palestinians. In Hidden Histories, under “claims” and “appropriation,” I cite more than 40 refutable claims and appropriations that cover aspects involving biblical stories, stipulated connections between present Jews and ancient Jews, or Israelites, as well as a range of fabricated or exaggerated ascriptions related to culture, foods, plants, sites, place names, languages, scripts, and other elements. These appropriations create a false nativity, magnifying Jewish connections and undermining or demonizing ancient and modern peoples. In this context, Palestinian existence and continuity over many millennia become invisible, camouflaged by this claim system through strategies of dismissal or justification (e.g., Palestinians are Muslims who came from the Arabian Peninsula, so don’t have the same ancient connections.)

Discoveries since the 19th century have debunked the historicity of a host of notions underpinning this Zionist system. Epigraphic and archaeological finds show that biblical accounts, such as the story of Nūh/Noah, were copied from more ancient regional myths, such as the story of the Mesopotamian flood . Among scholars who have come to these conclusions are Israelis, like archaeologist Ze’ev Herzog who summarizes as follows: “The patriarchs’ acts are legendary… the Israelites were never in Egypt, did not wander in the desert, did not conquer the land in a military campaign and did not pass it on to the 12 tribes of Israel. Perhaps even harder to swallow is the fact that the united monarchy of David and Solomon, which is described by the Bible as a regional power, was at most a small tribal kingdom. And it will come as an unpleasant shock to many that the God of Israel, Jehovah, had a female consort.”

Contrary to common impressions, people in Palestine were predominantly polytheistic in their religion, mostly Phoenicians, Greeks and Arab tribes. People in the region may have transitioned from one religion to the next, but they in general stayed where they were. Further, “exile” is “a myth” and the notion of a “Jewish people” is a historical fantasy, as shown by Arthur Koestler, Shlomo Sand and others. Nor are present Jews connected in any real way to ancient Jews or to “Israelites” and “Hebrews.” For present Jews to make these ancient links is like Muslims in Afghanistan or Indonesia saying they descend from Prophet Muhammad and have ownership rights to Mecca and Arabia as their ancestral homeland.

The Stones of Others: Israeli Judaizing Actions

Plans were ready, existing “laws” in place, new “laws” conveniently enacted for how to take over the stones built by other people and to control the demographics. It is a grand strategy that appears to have been prepared well in advance.

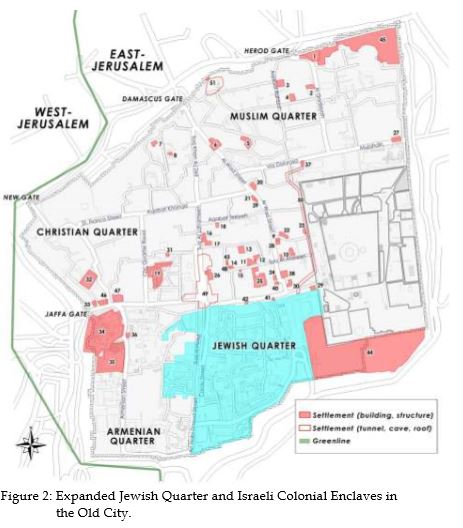

Judaizing the city has proceeded through expropriations within and outside the walls, expansion of the Jewish Quarter, establishing enclaves elsewhere in the Old City, ringing the city with colonies within arbitrarily expanded boundaries, manipulating a Jewish majority through measures to limit or reduce the Palestinian population by excluding/including areas using the separation wall, restricting family reunification and child registration, revoking residency status (see sections below), refusing permits, demolitions, and other regulations to constrain Palestinian building and development. These measures are being taken in addition to changes to street and place names that use Hebrew above Arabic and English names, changes made by committees which, in most cases, distort the original Arabic names into Hebrew phonetics.

Only three days after the June 1967 war ended, the Israelis demolished Hāret al-Maghāriba, Maghribi (Moroccan) Quarter, which dates back to the 12th century, in order to clear the area for a plaza in front of the Western or Wailing Wall. By June 11 the quarter was totally leveled, 135 houses demolished and 650 residents evicted. Among the demolished buildings were a mosque, Sufi prayer halls, and hostels. The renowned Khanqah al-Fakhriyya, adjacent to the Western Wall, a Sufi compound, was destroyed two years later by Israeli archaeological excavations. During the destruction of the quarter some residents refused to leave and stayed until just before the building collapsed. One woman was found dead in the rubble.

In 1968, Israel started the project to settle and expand the Jewish Quarter. As Meron Benvenesti and Michael Dumper point out, prior to 1948, the Jewish Quarter was less than 20% owned by Jews since most buildings were leased from the Islamic waqf or private family waqfs. While Jewish immigrants increased outside the city walls, in the quarter the Jewish population had declined well before 1948. At the end of fighting those who had stayed were removed to Israeli-held areas, the buildings partially used to house some West Jerusalem Palestinian refugees. Zionist writers make a point of repeating that this happened, that Jews had no access to the Western Wall or Mount of Olives between 1948 and 1967, a by-product of the conflict and hostilities; they forget that hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were evicted from West Jerusalem, other cities, towns and villages, their property taken, and that Israel had refused to allow any of them to return.

To implement this expansion, Israel expropriated more than 32 acres of Islamic and private Palestinian property, using the 1943 British ordinance and Absentees’ Property Law, between the Maghribi Quarter and the Armenian Convent, and from the Tarīq Bab al-Silsilah in the north to the city walls in the south. That included 700 stone buildings, of which only 105 had been owned by Jews before 1948. Palestinian property seized included 1,048 apartments and 437 workshops and commercial stores. (Even then-mayor of West Jerusalem Teddy Kollek objected, saying hundreds will lose their livelihood and thousands dispersed and, citing the expulsion of Palestinians from West Jerusalem in 1948, wondered when they would reclaim their property.)

Owners and those evicted were offered compensation, but the offer was essentially meaningless since waqf property trustees are prevented by shariʿah law from accepting any change in property status. The process took several years since most refused compensation. This resulted in litigation along with harassment and coercion. As still happens in takeovers, people who refuse have their entry blocked, surroundings demolished and are subjected to annoyances such as drilling and falling masonry.

In addition to the above, two other drastic developments occurred over the coming years: inserting enclaves in the Old City and building colonies around the city’s expanded municipal boundaries.

The enclaves within the Old City exhibit extreme ill-intention and are a constant source of tension. Other than the expanded Jewish Quarter, at least 78 properties within the walls have been seized and made into fortresses or mini-colonies. Figure 2, a partial indication with numbers, shows the extent of this cancerous infiltration. With government assistance and foreign Jewish money, extremist groups took over properties, using various pretexts and acquisition tricks, among them to locate and occupy properties previously owned or leased by Jews, remove protected Palestinian tenants, coerce tenants to sublet, and acquire by shady purchases that hide the source.

The drive by militant groups to establish a presence in the Muslim Quarter intensified after the rise of Likud and after Ariel Sharon, who was then Minister of Housing, in 1987, took hold of an apartment in a property in Al Wad Street owned by a Jewish Belarusian in the 1880s. (It is as if anything owned or leased by a Jew can be re-owned by any Jew, contrary to what is applicable to homes that were emptied of Palestinians in 1948 whose direct owners can’t claim them.) The drive for infiltration and acquisition has recently also been active in areas close to Jaffa Gate and around the periphery of the enlarged Jewish Quarter, it seems with the intention of expanding it further at the expense of the Muslim and Christian quarters.

Outside the Old City, as early as 1968, 17,300 acres were annexed to the municipal boundaries. These included the lands of 28 villages and some parts of Beit Lahm (Bethlehem), Beit Jala and Beit Sahour municipalities. Much more confiscation occurred in the West Bank, and by now in addition to all the colonies in the West Bank, in the area called Greater Jerusalem scores of Jewish-only colonies, which are increasing in number have been built of various sizes, some already cities, all the result of confiscation of mostly private land, as well as communal or public lands.

Colonies constructed since 1968 within the Israeli-declared Jerusalem municipality itself, include: Ramat Eshkol, French Hill or Givʿat Shapira (both on 1,186 acres, expropriated mostly from Sheikh Jarrah), Sanhedria Murhevet, Givʿat HaMivtar, Gilo (on land belonging to residents of Bethlehem, Beit Jala, Beit Safafa and Sharafat), Neve Ya‘akov (using the pretext of 16 Jewish-owned acres before 1948, Israel confiscated 3,500 acres of privately owned and titled Palestinian land for “public purposes”), Givʿat Hamatos, Ramot Alon (expropriated from Beit Iksa and Beit Hanina), Ma’alot Dafna (485 dunums expropriated from East Jerusalem and no-man’s land), East Talpiot (on more than a fifth of Sur Baher land), Pisgat Ze’ev (1,112 acres, seized from villagers of Beit Hanina, Hizma and Anata), Pisgat Amir (expropriated from the Palestinian village of Hizma), Ramat Shlomo called Reches Shuʿfat earlier (expropriated from Shuʿfat), Har Homa (1,300 dunums seized from private land owners from Beit Sahour and Sur Baher), Nof Zion (extending into the heart of the Palestinian neighborhood of Jabal el Mukabber), and Mamilla.

In the early 1970s, just outside the Israeli-declared municipal boundaries of Jerusalem, colonial growth proceeded at an equally brisk pace, with Ma‘aleh Adumim on lands confiscated from the town of Abu Dees achieving city status in 1991,with about 40,000 inhabitants.

Despite the Oslo Agreement, the Israeli government in 1995 started discussion of the “Greater Jerusalem” Master Plan with an outer ring of colonies, including Ma‘aleh Adumim, Givʿat Ze’ev (on public land, the site of a Jordanian camp), Har Adar (confiscated from Palestinian lands of Beit Surik and Qatanna), Kochav Yaʿakov and Tel Zion (on thousands of dunums confiscated from Palestinian villages of Kafr ʿAqab and Burqa), settlements east of Ramallah, Israeli buildings in Ras el-ʿAmud, Efrat, the Etzion Bloc and Beitar Illit—extending over more than 300 sq. km. of the West Bank. Such a Greater Jerusalem is aimed at strengthening Israeli domination in the central West Bank by adding 19 colonies into Jerusalem and a population of more than 150,000 Jews—for sure to finally kill any prospect for the establishment of a viable Palestinian state.

In 2017, a bill for Greater Jerusalem was introduced for a vote in the Knesset, and would likely have been approved except for some apparent U.S. and European pressure. It is clear, however, that the Israeli government and city officials are taking advantage of Trump’s policies to “push, push, push,” as one of them said, and to accelerate their building rampage and take other Judaizing measures while they have a freer hand.

Silwān has become another focus of Israeli acquisition, partly as a result of relative limitation in further expansion of enclaves within the Old City. Silwān is a town of about 35,000 Palestinian residents that borders the southern wall of the Old City. It is associated in part with what is called “the City of David.” Evidence points to continuous habitation since the fourth millennium BCE, but the fixation has been with the presumed Israelite period and the conquest by David. A Zionist archaeologist, Eilat Mazar, has claimed discovery of what remains from David’s palace, though many Israeli archaeologists say the findings contradict this claim.

The takeovers have accelerated in particular in the area called Wadi Hilweh and in al-Bustan neighborhood. Private, well-funded right-wing Zionist organizations such as Elad, as well as the Jewish National Fund, are used by the government, which hands over properties to them and protects their designs to control buildings and develop methods to settle Jews and dislocate Palestinians. Most properties in Silwān have been seized using the Absentees’ Property Law, though technically East Jerusalem had been declared by Israel to be exempt from it.

Elad has been given power by the government to run the “City of David National Park,” thus archaeological excavations are employed as another excuse to expropriate more Palestinian private land and to rewrite historical memory by misinterpreting and falsifying results. (A Byzantine water pit becomes the pit into which Jeremiah was thrown, according to Elad guides.) Plans for an archaeological/amusement park will lead to further destruction of Palestinian neighborhoods. By creating an archaeological tourist park dominated by extremist elements, Israel is intent on maintaining an exclusivist national narrative, the inventiveness about “David” being limitless.

This “Davidization” is going apace in other parts of the city, with an apparent design to join Silwān to the Jewish Quarter and the Tower of David area. In this effort to solidify an invented narrative, there has been a shift in the visualization of Jerusalem and its perception for tourists and Israelis, re-centering the gaze on the Tower of David and wielding new architecture and memorabilia to it, as argued by Dana Hercbergs and Chaim Noy (“Beholding the Holy City: Changes in the Iconic Representation of Jerusalem in the 21th Century”). Certainly, this narrative of making the Tower of David a museum of “Jewish history” is not only contradicted by its archaeology and history, but also by 17th-century minaret that tops the citadel and makes it a “tower”—though few tourists would raise a question. The mushrooming of Davids during the last decades has occurred with the speed and multiplication of other malignancies.

Laws

“Laws” have been issued ever since the beginning of the Israeli state in 1948 that have accumulated and intensified in their design to dispossess the Palestinian population and entrench Zionist exclusivity—a web of laws that can only be described as a parody in any sense of legality.

It’s a one-sided process. Where convenient, Israel has employed British mandatory land regulations, such as the 1943 Land Ordinance, and even Ottoman laws, to implement its expansion by expropriation. Other than the “right of return” for any Jew, the reverse of which is no return for any Palestinian forced to leave, the most flagrant legal tool is the Absentees’ Property Law (1950), signed by David Ben-Gurion as prime minister and Chaim Weizmann as president. The other instrumental laws were the Land Acquisition Law in 1953 and the Planning and Construction Law of 1965, which more or less completed the process of expropriation, though more disinheriting laws continue to be issued until today.

The 1950 law was devised for the purpose of disinheriting Palestinians and preventing their retrieval of properties (or their return), in order to establish Israeli control of land or houses and buildings owned by Palestinian refugees in cities, towns and destroyed or depopulated villages. It also applies to furnishings and valuables, bank accounts and other holdings, covering persons as “absentee” and property as “absentee property” even when “the identity of an absentee is unknown.”

An absentee’s dependent does not have rights if she/he happened to have stayed behind (no inheritance, as would have been normal) and any small allowance if paid to an unlikely dependent (only to one dependent in case there are more than one) is at the discretion of the appointed state custodian. The Israeli custodian has the power to liquidate businesses and annul business partnerships, to demolish buildings not authorized by the custodian, to sell or lease immovable property (through the Development Authority), and to rent buildings or allow cultivation of fertile land to a person (an Israeli Jew of course), with some income due to the custodian, but such that “his right shall have priority over any charge vested in another person theretofore.”

In one of the most incredulous sections (27), the law defines who could apply to be defined as “not an absentee”—only if that person left his residence “for fear that the enemies of Israel might cause him harm,” but excludes those who left “otherwise than by reason or for fear of military operations.” (In other words, it makes “not absentees” equivalent to Israelis who are not “absentee” anyway but beneficiaries from “absentees.”) Section 30 states that the “plea that a particular person is not an absentee … by reason only that he had no control over the causes for which he left his place of residence … shall not be heard” (presumably to apply to men who were not fighters, women and children, etc.). Thus, this “law” tries in every way to cover all the corners, to make sure that the original owners have no recourse to recover their rights under Israeli law. Israel creates such laws to say that what it is doing is legal, and to give its courts the tools to approve.

While this “law” was especially useful in the early years of the state, making possible expropriation of more than 6 million dunums of land, it is still being used today. The “law” is careful in defining “Palestinian citizens” (contrary to later Zionist denials that they exist), and in delineating for absenteeism the period 29 November 1947 to 19 May 1948 with the design to include the hundreds of thousands of properties lost in 1948. (“Present absentees” applied as well to more than 35,000 Palestinians who became Israeli citizens after 1948, and they or their descendants are still in that category.)

Since the illegal annexation of East Jerusalem, Israel has used the 1950 Absentees’ Property Law to confiscate properties from those classified by it as absentees although they are present. Technically absentees by Israeli definition, East Jerusalem residents were mostly exempt from this status in the Law and Administration Ordinance 5730-1970, section 3, thus considered “not absentee” only if they were physically present in Jerusalem on the day of annexation. However, that section excluded Palestinians who lived outside the municipal boundaries but owned land or property inside the city limits, or those who happened to be visiting outside the country. Occasionally after 1967 and after the 1980s, Israel and settler groups have found it expedient to apply the 1950 Absentees’ Property Law in places like Silwān and Sheikh Jarrah as well as in areas to the north of Beit Sahour, Beit Jala and Beit Lahm (Bethlehem) that were incorporated into the enlarged Jerusalem municipality.

As happened with Gilo in1970, 460 acres of land were expropriated in 1991 on Jabal Abu Ghneim south of Jerusalem to build a colony called Har Homa, which now has a population of more than 25,000 Israeli Jews. The residents of Beit Sahour, who owned the land, were thus declared “absentees” (since they were prevented from reaching it) and their lands seized without compensation or legal hearing. In addition to the plan within Greater Jerusalem, an objective was clearly stated that this expansion is intended to obstruct any future expansion of Beit Sahour and Bethlehem.

Another excuse used was that in the 1940s a Jewish group had purchased 32 acres, on the hill! The strategy is similar to some other locations such as the Jewish Quarter in Jerusalem, Hebron, and “Neveh Ya‘akov” colony, where a contention of some pre-1948 ownership was used to take much more land to build huge colonies and establish enclaves.

The Abandoned Areas Ordinance was an immediate measure taken on 30 June 1948 (retroactive to 16 May) to define abandoned areas as “any area or place conquered by or surrendered to armed forces or deserted by all or part of its inhabitants, and which has been declared by order to be an abandoned area.” The Ordinance provided for “the expropriation and confiscation of movable and immovable property, within any abandoned area” and authorized the Israeli government to determine what would be done with this property.

The 1953 Land Acquisition Law was the second law enacted after the Absentees’ Property Law as another step to wrest land from Palestinians. This law immediately confiscated an additional 1.3 million dunums of Palestinian land, affecting 349 towns and villages, in addition to the “built-up areas” of about 68 villages. This “law” completed the process of formal transfer of ownership, until then, of expropriated lands from their Palestinian Arab owners to various Israeli state institutions, and permitted the Minister of Finance to transfer ownership to the Development Authority. The authority to expropriate also resides in the Planning and Construction Law of 1965, and in a number of other legislative acts such as the Water Law, the Antiquities Law, Construction and Evacuation legislation, and others.

Several other “laws” are used to acquire Palestinian land. One is the Prescription Law, 5718-1958 enacted in 1958 and amended in 1965, which essentially repealed provisions of the 1858 Ottoman Land Code, and which also reverses some British practices of that law. It changes the criteria for Miri lands, or arable land whose cultivators were tenants of the state but entitled to pass it on to their heirs, one of the most common types in Palestine, in order to facilitate Israel’s acquisition of such land. According to the Centre on Housing Rights Evictions (COHRE) and the Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights (BADIL), the Prescription Law is one of the most critical to understanding the legal underpinnings of Israel’s acquisition of Palestinian lands, both in the period after 1948 and in the West Bank after the occupation of 1967. Although not readily apparent in the language, in conjunction with other land laws, this law enabled Israel to acquire lands in areas where Palestinians still dominated the population and could lay claims to the land.

Another is a leftover from the British Mandate, the Land Ordinance (Acquisition for Public Purposes) of 1943, which remained active for Israel because of its usefulness in enabling land expropriation, particularly in Jerusalem. After enlarging the municipal border, Israel gradually issued scores of orders expropriating several additional square kilometers for “green areas” under the provisions of this old regulation. Declared as “public parks,” the acquisitions are in fact designed not for “conservation,” but rather to prevent Palestinian development, to isolate Palestinian areas, to ensure the contiguity of Jewish areas, and to build for Israel’s purposes. Until now, four “national parks” have been declared in East Jerusalem, including on privately- owned Palestinian land and land adjacent to Palestinian neighborhoods or villages, with plans for more “parks” under way.

Israel also amends to serve its purposes. On 10 February 2010, the Knesset passed an amendment to the 1943 Land Ordinance (Acquisition for Public Purposes), with the primary aim of confirming state ownership of land confiscated from Palestinians, even where the land had not been used to serve the purpose for which it was originally confiscated. The amendment was devised to circumvent an Israeli Supreme Court decision (in the Karsik case of 2001), whose precedent Palestinian Israelis were planning to use to retrieve property. This amendment gives the state the right not to use the confiscated land for the specific purpose for which it was confiscated. It further establishes that a citizen does not have the right to demand the return of the confiscated land in the event it has not been used for the purpose for which it was originally confiscated, if ownership of the land has been transferred to a third party or if more than 25 years have passed since its confiscation. The new amendment also expands the authority of the Minister of Finance to confiscate land for “public purposes.” It defines “public purposes” to include the establishment of new towns and expansion of existing ones. The law also allows the Minister of Finance to change the purpose of the confiscation and declare a new purpose if the initial purpose had not been realized.

Such pliability in legal application is clear in Israel’s continued use of the Defence (Emergency) Regulations enacted by the British in 1945, with some modifications (although the Zionists were vehement in their attack on these British regulations before 1948). The regulations included provisions against illegal immigration, establishing military tribunals to try civilians without granting the right of appeal, conducting sweeping searches and seizures, prohibiting publication of books and newspapers, demolishing houses, detaining individuals administratively for an indefinite period, sealing off particular territories, and imposing curfews. In 1948, Israel incorporated the Defense Regulations, pursuant to section 11 of the Government and Law Arrangements Ordinance, except for “changes resulting from establishment of the State or its authorities.”

There was debate in the Knesset in the early 1950 about repealing the Defense Regulations for their undemocratic practices, but they were never abolished because they served the military rule imposed on the Palestinian Arabs who had remained in Israel and became citizens. After cancellation of military rule, a Ministry of Justice committee was entrusted with drawing up proposals for repeal, but the occupation of 1967 brought a stop to this process, and resulted in the Emergency Regulations (Judea and Samaria, and the Gaza Strip – Jurisdiction in Offenses and Legal Aid), whereby it was decided the Regulations were in effect as part of the status before the occupation and thus still in effect. Israel has since used these regulations to punish residents, demolish hundreds of houses, deport and detain thousands of people, impose closures and curfews, and other measures. These Regulations were amended in 2007, mainly to exclude Gaza.

In one instance the Israeli system tried to liquidate claims that could be lodged by Palestinians who lost their property, such as in an amendment in 1973 called Absentees’ Property (Compensation). This amendment devised a ghostly arrangement according to which Palestinian Arabs in “unified” East Jerusalem could receive compensation for their property elsewhere on the basis of its value in 1947. While the properties of tens of thousands of Palestinians who had left the Western sector had been transferred to the Custodian of Absentee Property, there was only a very small percentage remaining in East Jerusalem, and the majority who were no longer residents of Israel were still not entitled to claim compensation. Jews, too, were compensated for their property in the eastern part of the city where public structures were built, but here the sum was calculated according to the 1968 value. This of course resulted not only in uneven legal application, whereby Jews can make their claim and Palestinians cannot make theirs, but also a measure that could for propaganda purposes say the “Arab refugee” problem is being solved, but limits the compensation to residents of Israel, patently not refugees. In effect it is an erasure of the larger claims by hundreds of thousands of the dispossessed, ending up being a take-it-forever law since Israel could declare ownership reverted to it after the set period was over.

Demographic Control and Residency Regulation

In June 1967, Israel held a census in the annexed area. Those who were present were given the status of “permanent resident” in Israel – a legal status accorded to foreign nationals wishing to reside in Israel. Yet unlike immigrants who freely choose to live in Israel and can return to their country of origin, the Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem have no other home, no legal status in any other country, and did not choose to live in Israel. It is the State of Israel that occupied and annexed the land on which they live.

Permanent residency confers fewer rights than citizenship. It entitles the holder to live and work in Israel and to receive social benefits under the National Insurance Law, as well as health insurance. But permanent residents cannot participate in national elections – either as voters or as candidates – and cannot run for the office of mayor, although they are entitled to vote in local elections or run for the municipal council (although none have done so). And this residency can be lost.

The residency system imposes arduous requirements on Palestinians in order to maintain their status, with drastic consequences for those who don’t. If they happen to live outside the country for study or work more than seven years or if they take on another passport or take on residence in another country, or live outside the municipal boundaries, that automatically results in revocation of residency in Jerusalem. Some revocations have taken place for flimsier reasons, invoking the 1952 Law of Entry for anyone who does not maintain “a center of life” in Jerusalem (except Jews of course, who often shuttle back and forth from business and work abroad, and keep their apartments vacant in colonies). Jewish residents of Jerusalem who are Israeli citizens do not have to prove that they maintain a “center of life” in the city in order to safeguard their legal status, and many have dual citizenships.

Between the start of Israel’s occupation of East Jerusalem in 1967 and 2017, Israel has revoked the status of more than 15,000 Palestinians from East Jerusalem, according to the Interior Ministry, which means they lost the right to live there along with benefits for which residents pay taxes. The Law of Entry authorizes arrest and deportation for those found without legal status. Without legal status, Palestinians cannot formally work, move freely, renew driver’s licenses, or obtain birth certificates for children, needed to register them in school. The discriminatory system pushes many Palestinians to leave their home city in what amounts to forcible transfers, a serious violation of international law.

Permanent residents are required to submit requests for “family reunification” for spouses who are not technically residents. Since 1967, Israel has maintained a strict policy on requests of East Jerusalem Palestinians for “reunification” with spouses from the West Bank, Gaza or other countries. In July 2003, the Knesset passed a law barring these spouses from receiving permanent residency, other than extreme exceptions. The law effectively denies Palestinian East Jerusalem residents the possibility of living with spouses from Gaza or from other parts of the West Bank, and denies their children permanent residency status.

More than 10,000 children born to such “mixed” marriages are being refused registration as another measure to control the city’s Palestinian population. Israeli policy in East Jerusalem is geared toward pressuring Palestinians to leave in order to shape a geographical and demographic alternate reality.

Residency revocation is employed as well as collective punishment for the entire extended family after an attack on Israelis by a member of the family. In Jabal el Mukabber after such an attack, the mother and 12 family members, including minors, received notices from the Ministry of Interior revoking their residency. The Interior Minister stated that “anyone conspiring, planning or considering a terrorist attack will know that his family will pay dearly for his actions.”

“Loyalty to Israel” has become a law for occupied Jerusalemites. It was first applied “illegally” in 2006 by the Interior Minister who revoked the residency of four members of Hamas elected to the Palestinian Authority’s legislative council. The case was stuck in court for over a decade. In early 2016 and before the Israeli courts ruled on the issue, Israel’s Interior Ministry again invoked this power to strip three 18 and 19-year-old Palestinians of their IDs for throwing stones.

In September 2017, the High Court of Justice held that the Interior Ministry did not have the statutory authority to strip East Jerusalem ID holders of their legal status, but postponed the application of the decision for six months to permit the Knesset to pass a bill to provide for the statutory authority. Now a new “law” has been enacted (in March 2018) to take away the residency ID of anyone if there’s a “breach of loyalty” to Israel—that is, requiring the occupied person who has been placed in limbo (not a citizen of any country) to have loyalty to the occupier. Israel has “unified” the two parts of Jerusalem, but wants to keep Palestinian Jerusalemites outside the formula and makes all efforts to diminish their number.

With the scarcity or absence of building permits, some Palestinians improve or build without permits, and thus there have been hundreds of demolitions. Illegal settlements, however, are multiplying while Jewish building is not demolished but protected. Since 1967, there have been more than 25,000 home demolitions in the West Bank and more than 2,000 in East Jerusalem. Studies have shown that the rate of demolition for permit violators in East Jerusalem is more than twice as high as for similar Jewish violators in West Jerusalem. According to Meir Margalit, the demolitions and associated measures are part of the broader context of colonial control over land and processes similar to those implemented by white settlers in settler colonial societies worldwide.

Right of Birth vs Law of Return

Many countries have avoided holding Israel accountable under international law for its practices. Instead, in some countries like the U.S., huge amounts of tax-exempt money continue to be collected to support Israel’s colonizing activities. With U.S. recognition of “Jerusalem” as Israel’s capital, permission has been granted to the occupying power to continue to Judaize the city with impunity. The unevenness in the application of justice is abundantly flagrant.

Israel and Zionist organizations have successfully obtained reparations for Jewish suffering in WW2, not only from Germany but from other countries. The World Jewish Restitution Organization has repossessed property that belonged to people of Jewish background, sometimes with sketchy documentation. Even unidentified bank accounts and such items as jewelry and art work have been recovered. This ought to be a precedent that, under normal moral standards, applies to Palestinians who lost their homes and properties in 1948, in 1967 and later.

Being born in a place is enough in several countries for one to earn citizenship, regardless where the parents come from or their status. In the U.S., for example, this applies to children of people on temporary student or visitor’s visas, and, as in the case of the DACA issue, even those who arrived illegally as minors may eventually have a path to citizenship.

Not so in Israel, or in Jerusalem. Any Jew not born in Palestine or Israel, upon arrival in Israel, has the right to citizenship under Israeli law, a right denied to the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians born in the country before or after 1948. In Jerusalem, isolated from its natural rhythm by artificial barriers and colonies, children now born in it can go unrecognized and unregistered, while those already born in it are either not allowed into its compass or their official belonging to it is withdrawn arbitrarily and by force. Those Palestinians who remain in it as recognized residents, not citizens, are controlled in their rights and their future, their ability to develop constricted, and efforts continue to deplete their number.

This type of mentality and resultant policies would be made to stop in a normal world, as a perversion of law and any sense of truth. Adalah’s Discriminatory Laws Database lists over 65 Israeli laws that discriminate against Palestinian citizens in Israel, Palestinian residents of other occupied territories and in Jerusalem on the basis of national belonging and of being non-Jews, whether explicit or indirect in their implementation in various aspects of life. And now we have further confirmation of the apartheidist nature of the state in the “Basic Law: Israel as the Nation State of the Jewish People,” enacted on July 19, 2018.

In view of all the above, it was particularly jarring and patently absurd to watch the gleeful faces of Ivanka Trump, Jared Kushner, U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and billionaire Sheldon Adelson at the celebrations of the move of the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem. Fundamentalist preacher Robert Jeffress and other evangelicals spoke at the event and gave prayers, in effect reviving the old thinking that identified the U.S. national myth with biblical Israel as a justification for colonial expansion. Clearly, it reflected a dangerous alliance between rapacious Zionist colonization and blind evangelistic mania that harks back to the worst periods of colonization and surely negates the presumed spirituality and higher values “Jerusalem” is supposed to represent.

The history of Jerusalem has been so filled with imaginaries, investments, and inventions, which were generally somewhat benign, but are now exploited with dreadful designs and deceptions. It is an unusual situation that differs from other “holy” cities where the sacred is at least stabilized into mundane religiosity. The world must know that these “Holy Land” abuses are a parody of the holy.