From The Editor

After an unintended extended hiatus, The Link is back, more indebted than ever to the patience of our Reader.

It is a pleasure now to introduce you to AMEU’s new board president. Mimi Kirk picks up this Link thread on archaeology, where biblical historian George Wesley Buchanan left off in 2014 (v43/3). In that issue, Buchanan’s epiphany at the Spring of Siloam (shown here in David Roberts’ “Gihon Spring”) illuminated some of the shaky cornerstones on which contemporary Holy Land archaeology rests. When Dr. Buchanan died recently just shy of 100, his principal finding– that Solomon’s Temple was not built on the Temple Mount, Haram al Sharif— remained relevant not only to archaeologists, but to the many Palestinians in whose crosshairs their homes lie.

Approaching the subject from a different angle, Kirk looks at enabling actors from America’s Christian evangelical communities, and how their interests coincide with archaeologic pursuits in occupied Palestinian territories. She details the relationship between American Christian Zionists and powerbrokers from Israel and the U.S., exposing the cynical politics that lie behind the digging. The damage these craven partnerships has wrought was on particular display during the Trump era, when groups like John Hagee’s Christians United for Israel were enlisted by billionaire donors and political minions to serve extremist agendas. New theologies and so-called “prosperity gospels” lead legions of American evangelicals to effectively disavow core values of both church and state, leaving one to wonder, What master do they serve? In a closing paragraph, Mimi Kirk underscores the urgent need to reverse these destructive tides and undo some of the harm she chronicles from the City of David, Tel Shiloh and Qumran.

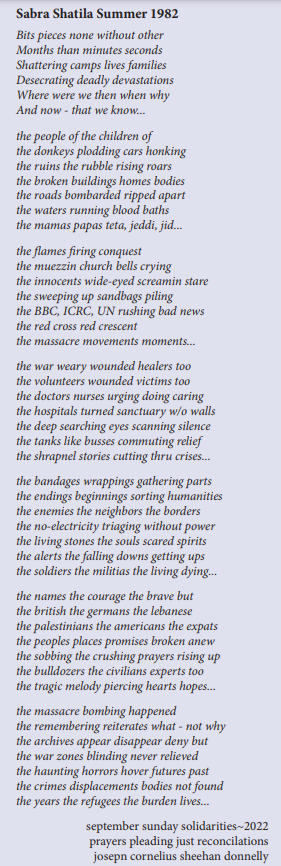

Separately, 40 years ago this month the literally unspeakable crimes of Sabra and Shatila unfolded. Just as we were about to go to press, a poet friend sent us his memory of the horror of those few days in Beirut. We share it on page 15, never forgetting the innocents who were massacred that September.

Lastly, on behalf of the AMEU board we are elated to announce The AMEU/John F. and Sharon Mahoney Award for Service, a new initiative to honor and amplify the work to which John’s four decade-long tenure continues to be devoted. The award will include a significant honorarium, and will be given each Fall to a person who has made — or will make– meaningful contributions to help Americans achieve a more complete understanding of the Middle East and its many peoples and traditions. The first awardee will be announced at the Fall meeting of the Board in November. More detail is available on-line at www.ameu.org.

Nicholas Griffin

Executive Director

The Politics of Archaeology – Christian Zionism and the Creation of Facts Underground

By Mimi Kirk

On November 18, 2020, Mike Pompeo became the first U.S. Secretary of State to visit the City of David archaeological park in East Jerusalem, a Jewish settler-run site near the Old City purporting to be the ancient seat of power of King David. The following day, he spoke about his visit at a press conference, turning toward then Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu who stood on the dais with him:

Last night I had a chance to walk through the City of David. Today you and I met looking out over the Old City. The peace, the increased prosperity, and the reduced risk to citizens all across the world and in the region and to here, in the Jewish homeland, that we have accomplished together is historic, and you should be proud.

Pompeo’s juxtaposition of the City of David and the current city of East Jerusalem was likely no accident. The City of David park is just one of many archaeological sites in Jerusalem and the West Bank that are illegal under international law and serve Israel’s settler colonial project by legitimizing the theft of Palestinian land and the dispossession of Palestinians through a (sometimes spurious) focus on the traces of ancient Jewish history at the expense of traces of other peoples also found in the archaeological record. Such a focus shores up the argument that the land “belongs” to Israeli Jews, who are simply “returning” to a home that was – and hence still is – theirs.

This use of archaeology stretches back to before the establishment of the Israeli state in 1948. Nadia Abu El-Haj, for instance, analyzes the collection of “ever more facts, cumulative instances of [ancient] Jewish art and architecture” during the period of the British Mandate (1923-1948):

This work of fact-collection needs to be understood as…about “world-making.” And in that work of world-making, the point of view of the archaeological relic…was fundamental. Archaeological relics were fetishized as…facts of ancient Jewish history through the perspective of which the land was fashioned as an old-new Jewish national home.

Even further back we find roots of this world-making work that are more religious in nature, specifically Christian. In the mid-nineteenth century, scientific research such as Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species increased interest among both the public and scholars in proving the opposite – that is, the factuality of the Bible. This period saw the advent of American and European archaeologists looking to link places, events, and people found in the Bible with archaeological remains, thus confirming the text’s veracity. Much interest, and therefore excavation, centered in and around Jerusalem.

Journalist Andrew Lawler notes that this new fascination was also related to the Protestant idea that the Jews must return to Jerusalem to facilitate the second coming of Christ, an interpretation of the Bible that rose in influence during this period. The belief is based in the idea that four millennia ago God promised the land of Israel to the Jews, who will rule it until Jesus’s return.

This interpretation became known as Christian Zionism, of which Mike Pompeo is an avid proponent. About 80 percent of evangelical Christians in the United States express the Christian Zionist belief that the modern state of Israel and the “regathering of millions of Jewish people” there is the fulfilment of biblical prophecy. As such, Israel and its settlements signal that this promise is growing closer to its realization: Jesus will soon return to Jerusalem and Christians will be saved via the rapture. For those with religious beliefs other than Christianity, they must convert or be sent to hell.

Archaeological projects that stress a Jewish relationship to and, the argument then goes, ownership of the land, are therefore supported by both Zionists and Christian Zionists. It is little surprise that leaders of the two ideologies – such as Pompeo and Netanyahu – would find common cause, despite the eventual hellfire ostensibly awaiting Jews in a Christian Zionist scenario.

This Link article first considers the roots and rise of Biblical archaeology – especially that originating in the United States – and its relationship to Zionism and the archaeological projects buttressing Israeli settler colonialism. It then considers three archaeological cases in which Zionists and Christian Zionists currently make particularly cozy bedfellows. Together, the history and the cases demonstrate Christian Zionism’s influence in archaeology in Israel and Palestine, as well as the role that evangelical forces in the United States play – ideologically, politically, and financially – in creating destructive “facts on the ground.”

From Puritanism to Christian Zionism

When the Puritans came to the “New World,” they brought with them the idea that they, in fleeing religious persecution in England, were the new Jews and America the new Israel, promised to them by God. As the Puritan John Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, proclaimed in 1630 in his famed “city on a hill” speech, “The Lord will be our God, and delight to dwell among us, as his own people, and will command a blessing upon us in all our ways…We shall find that the God of Israel is among us.”

Such an ideology, which most Protestants who came after the Puritans also held, meant a focus on the land of North America – but this did not mean that the Holy Land was forgotten. Burke Long argues in Imagining the Holy Land: Maps, Models, and Fantasy Travels that discourse around the Holy Land in the nineteenth-century United States reinforced American Protestants’ belief that their nation and religion were special and chosen by God. They believed, in essence, writes Brooke Sherrard, that “they were the ones attending to the legacy of biblical Israel.”

Sherrard, in her 2011 dissertation, “American Biblical Archaeologists and Zionism,” notes that Americans began to travel to the Holy Land in significant numbers in the 1830s and did so in a “distinctively Protestant way.” “Their desire to see the Bible lands was complicated by a rejection of traditional pilgrimage, especially the pilgrimage sites, which struck them as perfect examples of the accretion of Catholic tradition,” she writes.

These Protestants’ popular travelogues often lamented the fact that the land was not as bountiful as the Bible had described and blamed this on Arabs’ and Ottomans’ mismanagement – complementing the future Zionist myth that Jewish settlers have “made the desert bloom,” a fable that has endured. In 1979, for example, the Israeli scholar Yehoshuah Ben-Arieh wrote that at the beginning of the nineteenth century “Palestine was but a sad backwater of a crumbling empire – a far cry from the fertile, thriving land it had been in ancient times.” This myth continues to be deployed in support of Israel’s settler colonial project.

Nineteenth-century American Protestant travel writings about the Holy Land influenced how Americans

thought about the area and its inhabitants and set the stage for the U.S.-based Biblical archaeology that followed, which was also Protestant in nature. Edward Robinson, a Congregationalist minister from Connecticut, is considered by many scholars to be the father of American biblical archaeology. Journalist Lawler relates how when Robinson visited Germany in the 1830s he was dismayed to find biblical criticism in Protestant universities there, with scholars analyzing scripture the same way they would any ancient text. “Robinson was deeply concerned these scholars were calling into question what he cherished as the revealed truth of Scripture,” Lawler writes.

Robinson decided to counter this scholarship by documenting the remains of places, events, and people found in the Bible. Such a project took him to Jerusalem. “In 1839, he arrived…armed with a compass, measuring tape, telescope, and the Good Book as his guide,” writes Lawler. Though Robinson did not find the evidence he hoped for, such as remnants of the reign of Solomon, he documented the names of buildings, wells, and villages in the Old City and its surroundings that were reminiscent of monikers used in the Bible. In 1841 Robinson co-published the book Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea, which, as Lawler notes, “laid out [the] case for the Bible’s geographic accuracy.” A little more than 20 years later, in 1863, the Ottoman sultan in Istanbul issued the first license to a Westerner, a French senator named Louis Félicien de Saulcy, to excavate in Jerusalem, launching archaeology’s official quest to prove the veracity of scripture. (Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published four years prior, in 1859.)

British Protestants, as well as German and Russian archaeologists, soon after joined the race to discover Jerusalem’s biblical remains for both spiritual and material reasons. In the early twentieth century, for instance, British aristocrat Montagu Brownlow Parker estimated that the city’s artifacts, including the Ark of the Covenant – the chest described as holding the two stone tablets of the Ten Commandments – were worth $5.7 billion in today’s currency. (He failed to find anything after two years of digging.) Soon after, French-Jewish banker Edmond de Rothschild started his own archaeological search for the Ark of the Covenant, but had to abandon the dig with the outbreak of World War I.

By the mid-twentieth century, American biblical archaeology had branched out from being a mainly Protestant project to join forces with Catholicism and Judaism. Protestants, Catholics, and Jews were all reading the Old Testament steeped in the conviction that its historical passages described places, events, and people that had actually existed, occurred, and lived. Historian Kevin Schultz uses the term “Tri-Faith America” to describe the 1940s and 1950s, tracing how clergy fought for the three faiths to be considered equally American; they called this shared identity “the Judeo-Christian tradition.”

Sherrard’s dissertation traces the beliefs of a number of American biblical archaeologists of the mid-twentieth century, finding that those who envisioned the ancient Holy Land as comprised of cultures that interacted and merged with each other opposed the establishment of a Jewish state, whereas those who envisaged the ancient world’s ethnic boundaries as rigid and impermeable were in support of it. Still, Sherrard told me that all the biblical archaeologists she studied had Zionist leanings. “Even those who were against a Jewish state believed the migration of Jews to the land should be allowed,” she said. Some believed in the second coming of Jesus, though they were not “Christian Zionists,” per se.

Christian Zionism as the political ideology we see today emerged later in the twentieth century. While Christian Zionists (as well as evangelicals more broadly) tended to be apolitical throughout much of the century, the rights movements of the 1960s and 1970s helped politicize the demographic, particularly after the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion. Jerry Falwell’s 1979 Moral Majority platform, which opposed abortion, the equal rights amendment, and gay rights, also promoted U.S. support for Israel. Falwell and fellow influential Christian Zionists like Pat Robertson stressed the idea that God will only support the United States if the United States supports Israel – an idea often touted by today’s Christian Zionist preachers as it relates to economic gain. This “prosperity gospel” promises financial wealth granted by God to those who support Israel.

The election of Ronald Reagan in 1980 and his friendly relationship with Falwell and other conservative Christian leaders reinforced the connection between the Republican Party and the Moral Majority and gave Falwell’s movement access to politics, where it transformed into the “Christian right.” The presidencies of George W. Bush, a born-again Christian, and Donald Trump, who catered to his white evangelical base and chose Christian Zionists such as Mike Pompeo and Vice President Mike Pence to serve in government’s upper echelon, advanced Christian Zionism’s influence on U.S. politics and policy. The Trump administration’s move of the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, for instance, was done, as Trump said himself in 2020, “for the evangelicals.”

Today, though Trump is out of office, Christian Zionism’s influence continues, including in the field of archaeology. Archaeological sites in Jerusalem and the West Bank, some administered by settler organizations and many funded by evangelicals, collaborate with American archaeologists who espouse Christian Zionist beliefs. These sites also cater to American evangelical tourists by presenting the history of the Holy Land as exclusively – or at least primarily – Jewish, bolstering Jewish Israeli claims to the land. The following sections consider three sites where this ideological and political project is underway: Silwan in East Jerusalem and Tel Shiloh and Qumran in the West Bank.

Silwan and the City of David

The first archaeologist to begin excavations at Silwan was Captain Charles Warren of the London-based Palestine Exploration Fund, in 1867. In the more than 150 years since, as Jeffrey Yas notes in Jerusalem Quarterly, the village has grown up around a myriad of archaeological sites. “In many pre-1967 photographs,” he writes, “the wadi seems as much a place of excavation as residence.” After Israel’s occupation of the West Bank in that year, more Palestinians – many of them refugees – settled in Silwan.

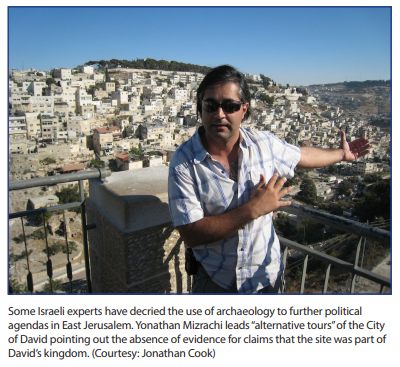

Today, the entrance to the City of David archaeological park sits near the edge of Silwan – though, as Yonathan Mizrachi, executive director of the Israeli NGO Emek Shaveh, which works to ensure that ancient sites are for all people, regardless of faith or ethnicity – says, visitors to the site are likely not aware that they are in a Palestinian area given the fences that mark excavations and surround Palestinian homes and the outsized presence of the park.

More than 600,000 people visited City of David in 2018 and even more in 2019, making it one of Jerusalem’s leading tourist sites. Sherrard calls the park “perhaps the clearest current example of the way the ancient past is employed as a tool [in Palestine],” and an Emek Shaveh report also emphasizes the site’s calculated use: “We believe that this project is one of the most prominent examples of how archaeology is used as a political tool to facilitate the appropriation of a public space.”

How does City of David carry out and accomplish such a scheme? Part of the answer lies in the group that runs the site, a settler organization called Elad (meaning “to the City of David”). Elad was founded in 1986 by David Be’eri, who left his post as deputy commander in an IDF unit whose members specialize in disguising themselves as Arabs, to establish Elad. Haaretz noted in 2011 that Be’eri employs Elad to “Judaize” Silwan, meaning to move Jewish settlers into the area while cleansing it of Palestinians. This is often done by demolishing Palestinian homes under the cover of law (Israel very rarely grants Palestinians permits to build, forecasting the situation of “illegal” home construction.) In 2011, around 500 settlers, protected by armed guards, had moved into the town. By 2021 2,800 settlers were living in Silwan.

Elad started to subsidize Silwan digs undertaken by the Israel Antiquities Authority in 1994. In the late 1990s, the government began the process of turning the site over to the group, and by 2002, as Natasha Roth-Rowland writes in +972 magazine, “the settlers had the City of David in their hands.” Elad presents the site as the land where King David established Jerusalem as his capital 3,000 years ago and where his son, Solomon, reigned afterward. There is no archaeological proof that these kings occupied the space, though Sherrard notes that the discovery of 8th and 7th century BCE coins bearing the names of Israelite royal family members indicate that it was an early Israelite area.

Visitors to the City of David are given a more skewed account. For instance, the main “evidence” of the presence of King David at the site is a line of stones running east to west that a biblical archaeologist, Eilat Mazar, identified in 2004 as likely part of King David’s palace. The marker in front of these stones quotes a Biblical reference to the construction of “David’s house” and favors Mazar’s findings, whereas the dominant belief among scholars is that the ruins are likely not from the time of King David, that is, the 10th century BCE, but are probably the ruins of a public structure built before then, in the 12th or 11th century BCE and that continued to be in use until the 9th or 8th century BCE.

“The archaeology here shows the opposite [of Mazar’s claim], that Jerusalem was here before the time of David and Solomon and after the time of David and Solomon,”

Says Mizrachi of Emek Shaveh. “But the average visitor… very much depends on the guidance they are getting from [Elad’s] inscriptions or tour guides and…this creates the feeling that you are in a Jewish, ancient Judean city that very much belongs to us-the Israelis.”

Moreover, much of the digging in Silwan occurs under Palestinian residences, causing structural damage such as long, jagged cracks in walls, floors, and yards. In 2017, 25 residents had to evacuate their homes because such damage made the structures unsafe to live in. Fayyad Abu Rmeleh told Al Jazeera in 2019 of his fear that the floor and yard of his home will collapse. “It’s putting our lives in danger,” he said. “Wherever you turn your head, you find new cracks.” Middle East Eye also reports that the archaeological tunnels have started to threaten the foundations of the Al Aqsa Mosque compound.

Elad is aware of the structural damage its activity is causing. David Be’eri describes an encounter in court where a judge approached him and said, ‘You’re digging under their houses,’ to which he replied, ‘I’m digging under their houses?! King David dug under their houses. I’m just cleaning.’ He said to ‘Clean as much as possible.’”

This archaeological “cleaning”, furthermore, is done using an outdated and problematic technique. Instead of excavating layer by layer, discovering the traces of people over time, as professional archaeologists do all over the world, the archaeologists at Silwan excavate horizontally – with the aim of emphasizing a particular period in history. Even the Israel Antiquities Authority has criticized this technique, saying that it constitutes “bad archaeology” and that “the authority could not be proud of this excavation.”

Another project in the works would “clean” the area not just under Palestinian homes but would remove them altogether. In the area adjacent to the City of David, there are plans to “re-create” King Solomon’s garden; this would mean demolishing dozens of Palestinian residences. Elad claims not to be part of the project, but regardless, the garden, along with the City of David and other Elad sites, would create “a contiguous Israeli touristic space” in East Jerusalem’s Palestinian neighborhoods.

Mizrachi notes that evangelical Christians have become more active in archaeological excavations in Jerusalem and the West Bank in the past few years, and says the City of David site caters to them. “It’s well known that a few years ago Elad said the City of David is open to all nations and to all religions – Jews and Christians. Not by mistake they are focusing on these two religions and not by mistake they [are omitting] other religions in this narrative,” he said.

One section of City of David that holds particular interest for Christians is the Pool of Siloam, where the New Testament recounts the story of Jesus putting clay on a blind man’s eyes and then sending him to wash them in the pool’s waters, which gave him sight. It’s unclear whether the pool at the City of David is the pool described in the Bible – Mizrachi notes that scholars don’t know the exact dates or use of it – but the site nonetheless touts it as part of the Christian tradition.

Elad has fashioned a subterranean path leading from this pool to the edge of the Haram al-Sharif called the “Pilgrimage Road,” said to be where Jews in ancient times ascended to the Temple to worship, which was inaugurated in June 2019 to great fanfare. U.S. guests included American Ambassador to Israel, David Friedman and Senator Lindsay Graham (R-SC), who along with then wife of the prime minister Sara Netanyahu, billionaire Trump supporters Sheldon and Miriam Adelson, and others took turns demolishing a faux-brick wall in an almost theatrical performance. Israeli archaeologist Raphael Greenberg described “sentiments related to Jewish suffering and redemption and…striving for emotional effect.”

Ambassador Friedman and Senator Graham are firm supporters of and are supported by Christians United for Israel (CUFI), the main U.S. Christian Zionist organization that boasts over 10 million members. They have spoken fervently at CUFI’s annual summit, as have Elad officials. At the 2019 summit, for example, Elad’s director of international affairs, Ze’ev Orenstein, declared, “We’re living in a time where, on the one hand, there’s unprecedented denial of the Jewish and Christian heritage in Jerusalem. But at the same time, there is unprecedented archaeological discoveries that are affirming our shared heritage in Jerusalem.”

Pastor John Hagee, who founded CUFI in 2006, expresses similar ideas about archaeology in Jerusalem. In a 2018 interview regarding the City of David, he proclaimed,

It is beyond reasonable doubt that this is, has been, and always shall be the property of the Jewish people. God established this place and this city to be the throne, the spiritual taproot, of Christianity and Judaism forever. And those who are trying to deny it are flying in the face of almost 4,000 years of history and hundreds of historical biblical facts that validate it beyond repudiation.

The archaeological “facts” that bolster the marriage between and goals of both Zionism and Christian Zionism may be most patently obvious in Jerusalem – and particularly Silwan – but a myriad of other archaeological sites in the West Bank similarly serve to shore up Israeli settler colonialism and the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians. At the site of Tel Shiloh, around 20 kilometers north of Ramallah, Christian Zionist archaeologists themselves are digging and working to create a version of history that legitimates Israeli land theft.

Tel Shiloh

Texas-based Christian Zionist archaeologist Scott Stripling began excavating at the site of Tel Shiloh in 2017. He told the Messianic/Christian online portal Kehila in 2019 that the Israel Antiquities Authority invited him to dig there, and that he prayed while considering the offer. But, he said, the praying “only lasted one day” because when he opened one of his Bibles the next morning, the page he landed on was Jeremiah 7:12: “Indeed, go now to My place that was in Shiloh, where I first made My Name dwell.” To Stripling, this was his clear answer.

The site of Tel Shiloh is located on privately owned Palestinian land, and Palestinian families farmed and lived there until the early 1980s, when the Israeli state evicted them to begin archaeological excavations. Tel Shiloh is now situated within the borders of the Jewish settlement of Shiloh and, like the City of David, is managed by settlers – in particular, a settler foundation and a regional council of Israeli settlements.

Christian Zionist archaeologists like Stripling are often allowed (or, according to him, invited) by Israel to dig in the West Bank, whereas they are not easily granted permits to work on the other side of the Green Line. Their findings are then taken by Israel, moved to storage units in Israeli settlements and to Israeli museums and universities – a violation under international law.

At Tel Shiloh, Stripling is searching for the remains of the biblical tabernacle – a portable dwelling containing the Ark of the Covenant. In the fall of 2021 Stripling told Katy Christian Magazine that he has become “more certain” that he has unearthed the tabernacle’s platform. The article notes that just one more excavation should provide “100 percent certainty…that the biblical information regarding the Ark is accurate.”

In fact, such a finding is extremely unlikely. Susanne Scholz, Southern Methodist University Professor of Old Testament, told me in 2020 that “properly credentialed biblical scholarship does not assume the historicity of anything prior to King David [ca. 1010-970 BCE]. That Stripling projects biblical stories into the historical record exposes him as a Christian fundamentalist. That’s the origin of his drive to do archaeology at Tel Shiloh.” Moreover, the main, substantiated findings at the site are primarily Christian and Muslim, such as Byzantine churches, including those that became mosques during the Arab period.

Regardless, it is the tabernacle story that is touted for residents and visitors alike. The settlement of Shiloh has a synagogue designed as a replica of it, and the archaeological site’s tourist attractions principally focus on the tabernacle. An audio-visual presentation prepared for visitors exemplifies the site’s ultra-Zionist (and Christian Zionist-friendly) messaging. The presentation depicts Shiloh-related biblical stories, beginning with the construction of the tabernacle and including the wars between the people of Israel and the Philistines. The war story shows the tribes of Israel separating rather than uniting in their fight. Emek Shaveh explains:

The act is presented as a moral transgression even though it was based on a majority decision…The underlying message…is that even a majority decision to cede parts of the Land of Israel is immoral and undermines the unity of the people. In contrast to this destructive process, Shiloh is presented as a place where unity is created and consensus is built among the people, a place that cultivates a positive force that enables settlement and building in the land.

In this way, the settlers present the history of Tel Shiloh, built on stolen Palestinian land, as a moralistic tale that legitimates their colonization of that land.

Stripling also calls Tel Shiloh Israel’s “first capital;” this is based on the notion that Shiloh was the Israelites’ first capital for approximately 400 years from the 15th century BCE. Though the claim is “utter nonsense,” according to Scholz, it’s an assertion that former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former governor of Arkansas Mike Huckabee, an evangelical, have also made.

Tel Shiloh’s association with the tabernacle and its supposed status as Israel’s first capital has made it a popular destination for Christian Zionists and evangelicals more broadly. An AP article noted that 30,000 people, of whom 60 percent identified as evangelical Christian, visited Tel Shiloh in 2009. Since the 2013 completion of a new visitor’s center – funded by the Israeli government – the number of visitors has increased substantially. In 2018, Tel Shiloh saw 120,000 visitors, with over half identifying as evangelical.

The settlers who run Tel Shiloh, along with Stripling and his team – a number of whom are “faithful Christians” who pay to be part of the dig – together work to strengthen a narrative in which Jewish ancient past and present are merged and Palestinians (and, indeed, any other people, past or present) are removed or hidden, thus legitimizing Israeli land theft and the human rights violations against Palestinians that accompany it.

The City of David corroborates and disseminates this narrative to an even larger audience, including thousands of Israeli school children. Those behind Tel Shiloh appear to be aiming for a similar role in the West Bank. Another West Bank site, Qumran, complements such projects and illustrates the part that archaeological funding from U.S. evangelical sources plays in cementing Israeli settler colonialism.

Qumran

The Dead Sea Scrolls, religious documents found in caves at a site called Qumran in the West Bank, about 45 kilometers east of Jerusalem, were first discovered in 1947. The manuscripts are thought to have been produced by a separatist sect of Judaism in the period before and after the birth of Jesus. Since their discovery – and especially after Israel occupied the West Bank in 1967 – Zionist and Christian Zionist archaeologists have conducted excavations in the area, looking to find more remnants of the sect who lived and practiced their beliefs there.

One such Christion Zionist archaeologist is Randall Price, a professor at Liberty University, an evangelical institution located in Lynchburg, Virginia and founded by Jerry Falwell in 1971. For two decades Price has conducted excavations in Qumran, in part under the auspices of the World of the Bible Ministries, whose website claims to help followers “discover factual context that reveals a deeper insight into scripture and prophecy,” principally through archaeology. Price has served as president of World of the Bible Ministries since 1993.

Price has written about his beliefs on a website called Rapture Ready, where he has argued for the “prophetical significance” of Israel, declaring, “It is only hoped that every student of the Bible will consider the historical events happening in the Middle East with the on-going Jewish return to Israel…in light of the prophetic scriptures.” Price’s Islamophobia is also on display; he asserts in another post that the United States “should be waging a war with Islam.”

In a 2013 Atlantic article entitled “The Biblical Pseudo-Archeologists Pillaging the West Bank,” author Dylan Bergeson recounts time spent with Price and his team of volunteers. In one scene, a volunteer named David gives Price his prized mini sledgehammer:

Holding a slip of paper high above his head, David announced, ‘It’s a 300-year contract! I made him sign it!’

‘David, I’ll leave it here because within the millennium this is probably where we’re coming,’ Price said.

‘Amen! Come Jesus!’ David cheered.

Price and his volunteers don’t work alone. Price’s excavations at Qumran are conducted in concert with Dr. Oren Gutfeld of the Institute of Archaeology at Hebrew University, giving them an air of respectability and demonstrating the intimate relations between Israeli institutions and Christian Zionists. (At Tel Shiloh, Scott Stripling also works with a number of Israeli archaeologists, such as Liora Freud of Tel Aviv University.)

The case of Qumran also reveals streams of funding from evangelical sources to Zionist/Christian Zionist digs, particularly from the United States. Israeli archaeologist Raphael Greenberg, a critic of such excavations and funding, has estimated that the majority of funds for archaeological digs in Israel and Palestine come from religious sources.

Though it is difficult to confirm such funding as church-affiliated organizations in the United States are not required to file tax documents that would reveal their donations, in the case of Qumran a paper trail points to a museum, the Washington, D.C.-based Museum of the Bible, founded by Steve Green, the evangelical billionaire president of the Hobby Lobby arts and crafts chain store. On its first 990 tax form in 2011, the museum’s mission was declared to be “to bring to life the living word of God, to tell its compelling story of preservation, and to inspire confidence in the absolute authority and reliability of

the Bible.”

The museum opened in 2017 with 16 fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls as its main attraction. Hobby Lobby purchased the fragments between 2009 and 2014, and the museum has also been in the business of supporting digs searching for related artifacts. In 2016 and 2017, the Museum of the Bible made $295,000 in donations to World of the Bible Ministries, Randall Price’s organization. (The 16 fragments were later removed from the exhibition after they were discovered to be fake.) Scholar Michael Press has argued that the museum’s financial support of such projects and institutions gives it “increasing power in determining…what material is studied and what isn’t, and how that material is analyzed.”

The Museum of the Bible’s 990 tax forms show that it also donates to archaeology-related evangelical and Christian Zionist institutions, such as the archaeology program at Wheaton College, a private evangelical school in Illinois, as well as programs like Passages, which has been called the Christian Zionist counterpart to Birthright. Passages takes Christian college students on trips to Israel to, in the words of Southern Methodist University Professor of Religious Studies Mark Chancey, “promote the political and theological views of Christian Zionism.”

Such funding is part of a larger trend of evangelical monies pouring into the West Bank, especially to settlements. In 2018, Haaretz published a report estimating that the amount of funding raised in the previous 10 years by evangelical organizations for projects in West Bank settlements was between $50 million and $65 million – and was growing. The report chronicled the increasingly cozy connection between evangelicals and religious Jews, noting that Trump’s policies done “for the evangelicals” had endeared evangelicals to settlers – of whom around two-thirds are religious. Shared conservative political views on gender relations, LGBTQ rights, minority rights, and other social issues have also drawn the groups into closer cooperation.

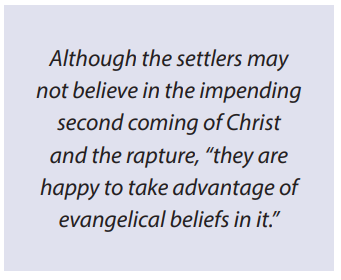

One way U.S. supporters describe and justify what is a fundamentally cynical partnership is through the trope of “Judeo-Christian heritage.” Tomer Persico, a fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem, told Haaretz that although the settlers may not believe in the impending second coming of Christ and the rapture, “they are happy to take advantage of evangelical beliefs in it.”

Conclusion: Archaeology, the JudeoChristian Narrative, and the Erasure of Palestinians

Less than two months after then-U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo toured the City of David archaeological park, as Donald Trump’s administration was ending, U.S. Ambassador to Israel David Friedman and Chair of the U.S. Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Paul Packer dedicated a plaque in the City’s “Pilgrimage Road” described above. The plaque proclaimed that America’s Founding Fathers looked to ancient Jewish Jerusalem for inspiration for their new country. The plaque reads: “The spiritual bedrock of our values as a nation comes from Jerusalem. It is upon these ideals that the American republic was founded, and the unbreakable bond between the United States and Israel was formed.”

In Ambassador Friedman’s speech that accompanied the dedication, he declared that “[the United States has] given this plaque…with the hope that it will prompt all who read it to think of the Judeo-Christian values upon which our country was founded and how those values were inspired by ancient Jerusalem and its inhabitants.”

While an emphasis on a Judeo-Christian tradition began in the United States in the mid-twentieth century as discussed above, beginning in the 1970s “Judeo-Christian values,” as James Loeffler

recently discussed in The Atlantic, became closely tied to the American right. “The phrase appears with regularity in rhetorical attacks on Islam and the progressive left,” he writes. In Friedman’s 2021 speech he similarly celebrates the Jewish and Christian nature of Jerusalem, purposefully excluding Muslims or any other faith group as historical as well as current inhabitants. (Palestinian Christians, in such a framework, are also ignored.) Pompeo likewise stressed the “fundamental moorings of the Judeo-Christian tradition on which [the U.S.] was founded” in a call with conservative pastors in 2020.

This emphasis on the “Judeo-Christian tradition” in relation to the practice of archaeology in Israel and Palestine provides a salient way for Zionists and Christian Zionists to collaborate and present a version of reality that legitimizes Israel’s treatment of the indigenous Palestinian population. It complements such tired tropes as those claiming that the land was empty before the Jews settled it (“a land without a people for a people without a land”), or, as mentioned above, that Jewish settlers have “made the desert bloom.” U.S. officialdom’s touting of “shared Judeo-Christian values” gives weight to this version of reality by eliding Palestinians’ presence in history or today, as do the Biblical archaeologists, evangelical funds, and thousands of Christian Zionist tourists that stream into ancient Holy Land sites from America and beyond every year.

The Trump administration both made clear the influence of Christian Zionism and bolstered that influence. With Trump out of office, it may be tempting to set aside concern regarding this ideological and political movement. However, Christian Zionism’s impact continues apace. As Palestinian-American activist Jonathan Brenneman recently noted, Christian Zionism is the world’s oldest and largest Zionist movement, and is the perhaps most extreme in its anti-Palestinian and anti-Muslim, not to mention anti-Semitic, anti-LGBTQ, anti-BIPOC, and anti-woman beliefs. In the struggle for Palestinian rights, calling out and working against Christian Zionism’s influence, including in the field of archaeology, is imperative.

Struggling to Remain in Silwan

An Interview with Fakhri Abu-Diab

Fakhri Abu-Diab was born in Silwan, East Jerusalem in 1962, making him at least the ninth generation of his family to live there. Historically known for farming, raising livestock, and craftsmanship, the Abu-Diabs live in Silwan’s Al-Bustan neighborhood, where plans are currently underway to demolish their and dozens of other Palestinian homes to make way for “King Solomon’s Garden.” Abu-Diab spoke with AMEU about Israel’s targeted displacement of

Palestinians, including through archaeological projects, and his and his neighbors’ fight to keep their ancestral lands and homes.

(Translated from the Arabic by Achref Chibani. This interview has been condensed and edited.)

Tell us about your land and home in Al-Bustan.

Before 1967, my mother farmed in Al-Bustan. When I got married, I promised to build my house nearby, on land that I had inherited from my ancestors and near where my mother had lived. I tried to obtain building permits and submitted structural maps and everything that the municipality requires several times. I applied to build a house where I could live with my wife and children according to the law and to the municipality’s requirements. However, the municipality did not let me build in this area.

Because I knew, as all Palestinian residents in this area know, that the municipality would not grant me a license, I eventually built a small home to shelter myself and my family on my land. After its completion and after living in it for about 10 years, around the year 2000, the municipality began to demand that we demolish the house on the grounds that we did not receive licenses from the municipality to construct it. Many Palestinians have experienced similar trials, having built homes on their land when the municipality would not grant them permits. Prosecutions and attempts to demolish our homes are ongoing.

How has the plan for “King Solomon’s Garden” affected you and other Palestinian residents?

In November 2004, the municipality issued an order to demolish 88 houses here under the pretext that that they were built on land of historical interest to the Jewish people, calling the area the King’s Park in relation to King David and King Solomon, who, according to the municipality, lived here and therefore the land should be turned into a national park.

The municipality imposed fines on us, which the residents of the area continue to pay. When these fines expire, they are automatically renewed, with the simple aim of exhausting us economically as well as psychologically. The municipality also breaks into our homes and delivers demolition orders, and when a period of demolition expires, new demolition orders are issued. The municipality seeks to frighten us and we are always subjected to harassment and raids. We spend much time with the lawyers who plead on our behalf or in the courts or with engineers or even with psychiatrists because of these prosecutions. We are anticipating the bulldozers every day. This affects us and our children psychologically, as we fear that at any moment we will become homeless.

How does Israel use archaeology in Silwan and elsewhere to displace Palestinian residents?

Israel uses antiquities to prove the existence of a history of the Jews and their civilization in this region, but it also uses them for politics, because the excavations cause the obliteration and destruction of our historical, human, and cultural heritage. It is mainly the settler associations that do this; they try to hide aspects of local history that do not fit their narratives and goals. It has been difficult for international institutions such as UNESCO and human rights organizations to become involved because the settlement associations obstruct external intervention as well as intervention from local residents or their official authorities.

Some homes above these excavations are old structures that the municipality cannot claim were built without a permit. These houses’ walls are cracking and are dangerous to inhabit because of these continued works. Instead of stopping the reasons for the cracks and putting an end to the excavations, the homes’ residents were given orders to leave. The municipality informed the owners that their houses may collapse and made them evacuate. The goal is to demolish our homes and then use the area for future settlement and Judaization projects.

How have you and your neighbors resisted?

Resistance to demolition first began with popular mass resistance. We started by setting up a sit-in tent near my house, and then moved it to a location close to all the residents of the neighborhood. I personally contacted many politicians and activists, and there were several protests near my home, in the streets, and in the municipality, and it was a successful method. We have also reached out to international institutions and diplomatic consuls and have relied on the media to make our voices heard and to share stories about the municipality’s intentions to demolish our homes and leave us without shelter. We have explained that the municipality declines our permit requests and at the same time gives settlers permits to build. These means of resistance were initially successful as the courts delayed demolitions for a period, but in the end, they granted the municipality the opportunity to demolish and impose fines on us.

Could you speak more about the history of Jerusalem and how it pertains to today’s residents?

We are also descendants of King Solomon and King David, and it is therefore our right to build and exist in this place. Moreover, it is most important to recognize human rights and to refrain from expelling, deporting, and forcing women, children, and entire families out on the street. People are more important than history. This does not mean that history and ancient civilizations are unimportant, but it is crucial to prioritize human survival and well-being. Otherwise, all people would have to be expelled from all the sites in the world. Hence, we ask: Why is there a focus on these particular gardens in Al-Bustan? Why is this where expulsion is occurring? Why is it that we do not hear of residents’ homes in the western part of Jerusalem being demolished and families being expelled to be replaced by settlers?

What do you want Link readers to particularly understand about Israel’s activities in Al-Bustan, Silwan, and beyond?

The demolition of homes and the expulsion of people, especially in areas that the international community considers occupied, are not permissible. In other words, Israeli demolitions, expulsions, and forced displacement of Palestinians are contrary to international charters and treaties and law. Despite this, we do not see any real moves from the international community to require Israel and the municipality to respect international law. Demolitions and displacement continue, as does our suffering.

We often wonder why the world deals in double standards and does not stand with us. We hope that the United Nations, international institutions, and those who establish so-called international law, treaties, and human protection defend us as our homes are being demolished and our children are put in extremely difficult physical and psychological circumstances. The stress that residents of Silwan must deal with because of the threats of demolition cause a majority of them to suffer from diabetes, high blood pressure, and other diseases. Our psychological and economic situation is very difficult, and while we see denunciations against Israeli violations here and there, we do not see any real change on the ground.

Thank you for this very informative article. As a former Christian Zionist I repent of my past words against the Palestinians. May the Father of my Lord Jesus Christ open the eyes of many more to the truth.