| Also in this issue: The Link Author’s Book |

By Miko Peled

I would like Americans

to know what

my mother told me.

I can’t recall how old I was when my mother told me this story, I only remember that it troubled me for many years. It was not until I was in my late 40’s that I understood what the story meant and why it disturbed me.

It was 1948 in Jerusalem and Zika Katsnelson-Peled, my mother, was 22 years old. She was a daughter of the Zionist elite. Her father, Dr. Avraham Katsnelson, was a member of the provisional Zionist government in Palestine and later a signatory of Israel’s Declaration of Independence. Her mother, Dr. Sima Kaplan, was a dermatologist and one of the first female doctors in Palestine. They all shared a small apartment in Jerusalem, where my mother herself was born and raised.

In the spring of 1948, the Haganah (the Zionist militia which later became the Israeli Defense Forces, or IDF) took the neighborhoods of western Jerusalem, including Katamon, Talbiye, and Bak’a, among others.

The inhabitants of these neighborhoods, like hundreds of thousands of Palestinians across the country, were forced to leave their homes and go into indefinite exile. The homes in these neighborhoods still stand, impressive houses built with distinctive Jerusalem stone. They generally have wide balconies overlooking front yards, a lemon tree in the backyard, high arched ceilings, and oftentimes an inscription with the date that the home was constructed. These were the homes of well-to-do Jerusalemite Palestinians who were all forced to leave, and never allowed to return.

The invading Zionist militia looted the furniture, rugs and other valuables such as rare books and manuscripts and, according to a 2013 documentary film by Benny Brunner, “The Great Book Robbery,” the Zionists even had a special librarian unit that followed the forces to collect and index the books they found. As the daughter of a member of the Zionist elite and the wife of a captain in the Haganah’s Giv’ati brigade, my mother was offered one of these looted homes, as were a handful of other Israeli families. She refused.

At this point my mother would add:

I knew the Palestinian families as a child growing up in Jerusalem. How could I take the home of another mother knowing full well that the rightful owners of these homes were now refugees?

And she would continue:

To see how the soldiers looted these homes, taking the rugs and furniture. How were they not ashamed? And you know, when the soldiers came into the homes, the coffee was still warm, sitting on the breakfast table.

And that was it. That was the story. We forced people to leave, we stole their possessions and we took their homes. How that story bothered me, for years. It bothered me because, in my mind, it couldn’t be true. I was taught that we are Israelis, we are the Jewish people, and we are righteous. We accepted the U.N. partition resolution of 1947 even though it only gave us a portion of Eretz Israel and not all of it, as we deserved. We wanted peace yet Arab bandits who wanted to kill us viciously attacked us and we acted humanely towards them, making sure not to harm women and children. We miraculously survived the war of 1948, defeated the advancing Arab armies and were able to establish a Jewish state in the land of Israel after 2000 years in exile.

So what was my mother saying? Why was my mother presenting a moral dilemma where there couldn’t be one?

One aspect of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict that makes it unique is that the disagreement is not merely over land rights, or an interpretation of history, but rather over the facts themselves. The Israeli and Palestinian narratives are diametrically opposed in that they claim two separate sets of historical facts, creating a situation where no middle ground, no “balance” can be found. If two opposing histories are presented, then one of them must be wrong. And indeed one of them is wrong.

The Israeli narrative begins with the right of Jewish people to “return” to their ancestral homeland. This so-called “return” is their right because the Jewish people of today claim to be the descendants of the ancient Hebrews who resided on that piece of land some two or three thousand years ago. In response to intolerance by regimes in Christian Europe towards their Jewish population, the Zionist movement was established and took on the task of recreating a state for the Jewish people in their ancient homeland. After decades of diligence, and what can only be described as diplomatic ingenuity, Zionist leaders like my grandfather managed to convince the world that this was a valid argument. Their hard work and dedication paid off and, on Nov. 29, 1947, the United Nations passed Resolution 181 that called for the partition of Palestine, and the allocation of the larger part of the country for a Jewish state.

According to the Zionist narrative, the Arabs rejected the resolution and immediately Arab forces began attacking the Jewish community in an attempt to destroy what the Zionists were trying to build. This narrative claims that the Jewish community prevailed, despite being smaller and weaker than the Arabs, resulting in the establishment of the state of Israel on May 15, 1948. The war continued until cease-fire agreements were signed between Israel and the neighboring countries in January of 1949.

The Zionist version of the story claims that the Arabs of Israel, the Palestinians, were asked by the Zionist leadership to remain but that, prompted by their leaders, they opted to leave, which led to nearly one million Palestinians ending up in exile. If all this were true then why did my mother describe this as though taking an Arab home was a moral dilemma? They themselves chose to flee, did they not? There could be no moral dilemma if the story as I knew it were true.

This story is not only romantic and heroic, but it is also unbelievable. As a child I remember reading about battles won by the Zionist forces, tough battles which my father fought and won alongside his comrades in arms, men whom I knew and who had become living legends by the time I was old enough to meet them.

But as one grows older, hopefully, maturity sets in. One aspect of maturity is close examination of the stories we heard as children, and a close examination of the story of the birth of Israel reveals the following: by 1947 the Jewish community in Palestine numbered close to half a million people, mostly immigrants like my grandparents, and their children, my parents’ generation. The Palestinian community, numbered close to 1.5 million. This explains the Palestinian rejection of a plan that was to give a small community of Jewish immigrants the lion’s share of Palestine. While both communities had already begun developing institutions of state, one thing in which the Jewish community had invested heavily, while the Palestinians had not, was an armed militia.

By 1947 the Zionist militia numbered close to 40,000 armed, well-trained men, many of whom were trained by the British. There was no Palestinian equivalent to the Zionist militia. So the question that begs to be asked is: if the Palestinians had no armed militia, who then were the Arabs who attacked the Jewish community? Armies of neighboring countries intervened in Palestine, but that wasn’t until the fighting had been going on for months, and mostly after the British had left Palestine in May of 1948.

So, it turns out that the Zionist claim that Arabs attacked after rejecting the partition plan is false. Once the United Nations passed the partition resolution, the Zionist forces began an all out campaign that can best be described as an unprovoked terrorist attack for the purpose of destroying the indigenous Arab Palestinian community in Palestine through ethnic cleansing. My mother’s story was the first hint that what I was taught in school was not entirely true.

I would like Americans

to know what

Moshe Dayan said.

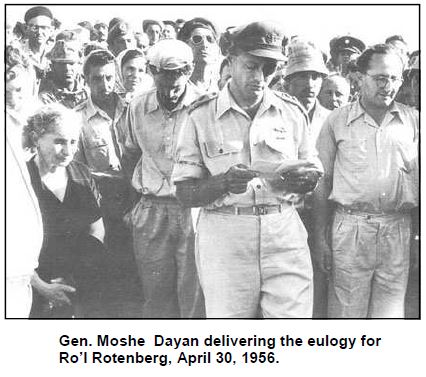

Arguably, the finest expression of the fundamental point of view of militant Zionism was a eulogy written and delivered by Gen. Moshe Dayan some eight years after the founding of the state of Israel. The occasion was the funeral of Ro’i Rotenberg, a 21-year-old officer in charge of security in the Israeli settlement of Nahal Oz, a settlement that had been established near Israel’s border with the Gaza Strip. Ro’i himself was one of the pioneer settlers of Nahal Oz. The date was April, 1956, when Ro’i was notified that Arabs were working in a field near the border. As he rushed on horseback to see what was happening, he was ambushed and killed by Palestinians from Gaza.

His funeral was held on April 30, 1956, just five months prior to the start of the Suez war, a war against Egypt for which David Ben-Gurion and Dayan were pushing fiercely. At the funeral, Dayan seized the moment to make the case for an all-out war. He gave a brilliant speech of only 238 words that was to become the Israeli equivalent of the Gettysburg Address. According to the late Israeli sociologist Baruch Kimmerling in his article “Militarism in Israeli Society,” this eulogy codified what would become the dominant characteristics of Israeli identity.

The following are excerpts that I have translated from Dayan’s speech:

How can we blame them (the Arabs who murdered Ro’i, ) for hating us? For eight years they have been sitting in refugee camps, while in front of their very eyes, we turn their land and the land of their forefathers into our homeland. Not of the Arabs of Gaza must we demand an answer but of ourselves. How could we have been so blind as to forget our destiny, the destiny of our generation, cruel as it may be?

Dayan goes on to speak of the gates of Gaza, evoking memories of biblical days when the Philistines of Gaza were enemies of the ancient Hebrews. He describes what lies beyond those gates today:

Hundreds of thousands of eyes and hands who pray for us to show weakness, so that they may tear us to pieces. Have we forgotten this? In order for their desire to destroy us to diminish, we must be armed and ready day and night. We are a generation of colonizers and without the helmet and the armor we will not be able to plant a tree or build a home.

Beyond these boun-daries is an ocean of hatred and revenge that awaits the moment complacency takes the place of our readiness, the day we heed ambassadors of hypocrisy (referring to U.N. Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld who was in the region trying to broker an agreement and avoid an all-out war between Israel and Egypt) who call upon us to lay down our weapons.

We must never cease to look straight at the hatred that accompanies and indeed fills the lives of hundreds of thousands of Arabs who sit around us and await the moment when their arm can reach out and spill our blood.

It is the destiny of our generation, the core of our existence, to remain alert and armed, strong and unyielding, for if the sword were to fall from our fist—we will be cut down.

One would be hard pressed to find a more eloquent expression of the attitude that has dominated, and indeed still dominates Israeli life and politics. Gaza was made to embody all that Israelis feared: poor, angry Arabs who hate us. Dayan admits to the injustice and the tragedy of refugees who yearn to return to their homes, but are forbidden from doing so by Israel. But, he says, “it is our destiny as Israelis and now we must live with the consequences.”

Expressed so poetically by one of the greatest icons of Zionism, the General with the Eye Patch, Moshe Dayan, this became the doctrine that guided Israeli policy towards the Arabs. Generation after generation of young Jews in Israel and in Zionist communities around the world have been educated according to it: Arab hatred towards us Jews is incurable and therefore a constant state of war is inevitable. This, one can argue, is the foundation of the Israeli mindset.

I would like Americans

to know what

my father said.

In 1967 Israel had conquered the remaining 22% of Palestine that was left outside the boundaries of the Jewish state in 1948. The generals who made up the army’s high command congratulated themselves on “finishing the job” of conquering the land of Israel so that it can be given in its entirety to its rightful owners, the Jewish people. That war sealed the fate of Palestine and its people. They rightfully call it “Naqsat Huzeiran” or the “June Disaster.” In many ways, one could say it also sealed the fate of Israel, turning it into a bi-national state.

As soon as the conquest of the West Bank was complete, Israel repeated what it did during and immediately after the war of 1948: a campaign of destruction, ethnic cleansing, and massive building for Israeli Jews. A few moderate forces within Israel did call on the government to initiate a peace process with the Palestinians. They suggested a formula that would include an Israeli retreat from the newly conquered territories and allow for a Palestinian state on the West Bank and Gaza Strip. But the more dominant powers in Israel strove to make the conquests of the territories irreversible.

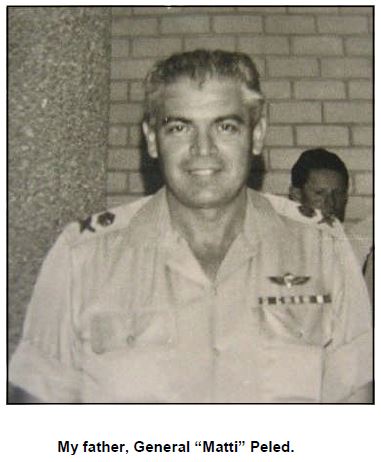

My father was Mattiyahu “Matti” Peled. Born in Haifa in 1923, he grew up a Zionist to the core. Until the day he died he believed in the need for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. He fought fiercely in Israel’s 1948 War of Independence and was one of its top generals in the 1967 war. Between those two “wars” was the Sinai Campaign of 1956, when Israel first captured the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula. By then a full colonel, he was appointed military governor of the Gaza Strip, a post he held until the occupation ended six months later when a furious President Eisenhower demanded that Israel evacuate its troops and return to its pre-war boundaries. One night—I was in high school at the time—he spoke to me of his time in Gaza; what he told me explains much about my father and his later actions:

When I was given the orders that described my role as military governor, I was aghast. They were identical to those of the British high commissioner, or governor of Palestine. I was not only representing the foreign occupier, I was the governor. I could not help recall how I, as a young man, was determined to fight the British who ruled Palestine and whom I considered foreign occupiers. You really never know how things will turn out in the world.

My father regretted the fact that he knew virtually nothing of the language, culture, or way of life of the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians for whom he was responsible. Nor did he like the fact that he required translators to communicate with the people he governed. (At that time he made a personal decision to study Arabic, eventually receiving a bachelor’s degree in Arabic from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and a later a PhD at the University of California, Los Angeles, all in preparation for his second career as a professor of modern Arabic literature.) Most significantly, my father wrote:

In conversations with the locals, I was amazed to learn that they were not seeking vengeance for the hardship we caused them, nor did they wish to get rid of us. They were realistic and pragmatic and wanted to be free.

This was a direct challenge to the Dayan doctrine, and in 1967, when Israel took over the last 22% of historic Palestine, while the other generals were beaming with the glow of victory, my father spoke of the unique opportunity the victory offered Israel to solve the Palestinian problem once and for all:

For the first time in Israel’s history, we are faced with the Palestinians, without other Arab countries dividing us. Now we have a chance to offer the Palestinians a state of their own.

My father went on to warn that, holding on to the West Bank was contrary to Israel’s long-term strategy of maintaining a secure Jewish democracy with a stable Jewish majority; indeed, this would turn the Jewish state into an increasingly brutal occupying power and eventually into a bi-national state. In 1975, along with veteran journalist Uri Avnery, among other peace activists, my father founded the Israeli Council for Israeli-Palestinian Peace. Its aim was to bring about official negotiations between the government of Israel and the leadership of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (P.L.O.), leading to an independent Palestinian state. They were approached by the P.L.O. leadership to begin a dialogue and the first contact was held in Paris in 1976. But the die was already being cast, as one Israeli administration after another moved to integrate the West Bank into Israel, settlement by settlement.

I would like Americans

to know what

Max Gaylard said.

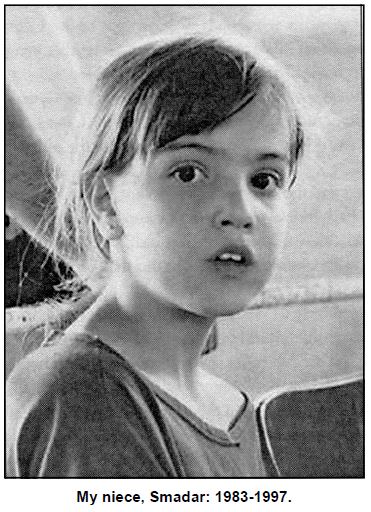

My journey into Palestine began in San Diego in the year 2000. I was 39 years old. What pushed me to embark on this journey was the death of my 13-year-old niece Smadar Elhanan in a suicide attack in Jerusalem. She was killed on September 4, 1997. I was living in the U.S. at the time, and after the funeral and the seven-day mourning period were over, I felt compelled to get involved.

It took three years and total disillusionment with the Oslo peace process before I finally found what I was looking for. It was a Jewish-Palestinian dialogue group that was meeting in San Diego where I live. Though I was born and raised in the “mixed” city of Jerusalem, the segregation that exists in the city creates a reality whereby Israelis have no real personal contact with Palestinians. This was my first personal encounter with Palestinians.

But not only was this my first encounter with Palestinians, this was the first time I had been with Palestinians in a place where we were equal before the law. More accurately, there were no restrictions placed upon the Palestinians, as there are in Israel/Palestine. There were no laws that limited their rights, there were no degrading checkpoints they had to cross, no permits they were required to show in order to come to the meetings, and they had no imposed curfew. This reality does not exist in Israel/Palestine. Several Israelis had called me asking why I would ever agree to meet with such “extremists.” “Extremists” is the word they use to describe Palestinians who do not accept the Israeli narrative.

Over the ensuing years my journey into Palestine has taken me to a part of my homeland that I did not know existed, even though I was born and raised there. And it introduced me to a people I had never met, though they were my neighbors, and to a culture I was not familiar with, even though it was all around me.

I began by traveling into Palestinian communities within Israel. First I went to Nazareth to meet friends, then to Umm El Fahm. Being in areas within Israel that are predominantly Palestinian was frightening enough, but nowhere near as frightening as when I set off to travel into the West Bank on my own for the first time.

The process by which I overcame this fear is described in detail in my book “The General’s Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine.” It is a process by which we cease to see the “other” as an enemy. Instead we begin to realize that that “other” is a fellow human, a neighbor and eventually a partner. It is trust replacing fear.

In January 2013, I was able to visit Gaza. I had been trying for several years, but all my attempts were unsuccessful. Israeli law prohibits Israeli citizens from entering Gaza, which means I cannot enter through the Israeli-controlled side. And for reasons beyond my understanding, I have been denied entry by the Egyptian authorities to enter Gaza. So, when the suggestion to enter via a tunnel was brought to my attention, I was eager to try again.

It was late at night when I entered the tunnel in Rafah. There are close to 1,500 tunnels that connect the Gaza Strip with the Egyptian side of Rafah. These tunnels are a vital lifeline for the 1.6 million citizens of Gaza, bringing in needed food, medicines, oil, and money. They are practically the only way in and out.

In the summer of June 2012 I had an opportunity to meet Max Gaylard in Jerusalem. He is a distinguished Australian diplomat and former United Nations Resident Humanitarian Coordinator for the occupied Palestinian territories. A year after Israel’s Dec. 27, 2008 to Jan. 18, 2009 assault on Gaza, he issued a dire report warning that:

The continuing closure of the Gaza Strip is undermining the functioning of the health care system and putting at risk the health of 1.4 million people in Gaza. It is causing on-going deterioration in the social, economic and environmental determinants of health. It is hampering the provision of medical supplies and the training of health staff and it is preventing patients with serious medical conditions getting timely specialized treatment outside Gaza.

Gaylard went on to talk about the children of Gaza:

More than 750,000 children live in Gaza. The humanitarian community is gravely concerned about the future of this generation whose health needs are not being met. The decline in infant mortality, which has occurred steadily over recent decades, has stalled in the last few years.

On Aug. 27, 2012, Gaylard held another news conference in Jerusalem in which he again warned:

Gaza will have half a million more people by 2020 while its economy will grow only slowly. In consequence, the people of Gaza will have an even harder time getting enough drinking water and electricity, or sending their children to school.

This is the Gaza I visited. My host during my stay was Dr. Mahmoud Ajrami, a veteran of The Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine. After years in exile, he returned to Gaza and served under both Fatah and Hamas-led Palestinian governments as ambassador and deputy foreign minister. He now heads The Academy for Administrative, Political and Strategic Studies in Gaza. Since he is neither a Fatah nor a Hamas member, he is an excellent spokesman for Palestinians in general and he offers a unique perspective on life in Gaza. “Under Hamas,” he told me, “there are 60 times more roads paved in Gaza than under the previous government. See the policemen in the intersections managing the traffic? In the past they would sit in the corner and do nothing, just smoke.”

Yousef Aljamal, a razor-sharp young writer and activist from Gaza who has made it his life’s mission to let the world know what happens in Gaza, coordinated my trip, showing me around Gaza, where I witnessed first-hand the conditions Max Gaylard described.

We stopped at a street-side stall for breakfast of hummus, falafel and fresh bread, then continued on to the Jabaliya refugee camp, and then to Al Shati camp on the coast, also known as the “Beach Refugee Camp.” I heard that Palestinian prime minister Ismail Hanniya still lives in the camp, in the home in which he grew up.

Walking along the beach, we passed a donkey-drawn cart filled with seawater-soaked gravel, and watched the poor donkey being pushed along by five young boys. Seeing this in Gaza is not uncommon, whereas half a mile up the coast, in the Israeli city of Ashkelon, a scene like this would not be possible. The development and prosperity that one sees in Israeli cities along the coast could be possible in Gaza if Israel allowed it. Sadly, debris from buildings destroyed during Israeli shelling and sewage from a water treatment plant also shelled by Israel pollute the Gaza coastline.

Yousef took me to the Center for Political and Development Studies and there, after an introduction given by Dr. Mahmoud, I gave my first lecture. It was quite moving. Here I was, the son of a former Israeli military governor of Gaza, giving a lecture in Gaza to Palestinians still under Israeli control. So what could I possibly tell people in Gaza that they did not already know? I told them about my journey from Zionism to becoming a pro-Palestinian activist who rejects Zionism completely.

Later that day, Dr. Mahmoud took me to the Academy for Administrative, Political and Strategic Studies, and there I gave another talk in front of an audience that included mostly faculty from the academy and other academic institutions is Gaza.

After four days, Dr. Mahmoud drove me back to Rafah, from where I was to tunnel back into Egypt. As we drove, we played a CD of the Palestinian poet Rafeef Ziadah reading her poetry. During Israel’s attack on Gaza in the winter of 2008-2009, a journalist had asked her “Don’t you think it would all be fine if you just stopped teaching your children to hate?” Ziadah’s response, by way of a poem, was:

We teach life, sir.

We Palestinians teach life after they have occupied the last sky.

We teach life after they have built their settlements and apartheid walls after the last sky.

We teach life, sir.

I would like Americans

to know what

Abu Ali Shahin said.

Over the past 65 years, Israeli attacks have been a constant part of life in Gaza, and one can safely assume they will continue. This is because, in the absence of attacks, Israel will be forced to engage in a solution of the Palestinian issue and, in particular, of the refugee issue. These are two issues, among several, that Israel does not wish to resolve.

Recent Israeli attacks on Gaza are being justified because they target Hamas, which has been labeled a terrorist organization. In fact, they have nothing to do with Hamas. The attacks are part of a strategy designed to bring the people of Gaza to their knees. For over six decades the people of Gaza have been struggling for their freedom and for their right to return to their lands, and for over six decades, on a regular basis, Israel has engaged in collective, punitive assaults on Gaza.

In the early 1950’s Palestinian refugees would try to return to their homeland, which was now the State of Israel. They were classified as “infiltrators” and a law was passed in Israel that made it illegal for them to enter. The refugees would enter their lands trying to retrieve food from their homes or crops from their fields, and from time to time they would enter as part of the armed resistance to attack targets inside Israel.

In 1953 Israel passed the “retribution act” which was a call for retribution against Palestinian infiltrators. Each time Palestinians were caught entering what was now Israeli territory, Israeli forces would enter Gaza or the West Bank to punish them. Ariel Sharon was commander of Unit 101, which was established for this purpose.

Sharon, then a young major, constantly asked the military high command for the green light to execute more such acts, and more often than not, his requests were granted. When he was criticized for killing civilians, including children, Sharon replied: “The women are whores. They serve the Arab militia men who infiltrate into our communities and attack the citizens of our country. If we don’t act against the refugee camps, it would become a murderers’ nest.”

Israel occupied Gaza in 1956 and then again in 1967. Days after occupying the strip in 1967 an Israeli army unit conducted a massacre in a neighborhood in the Rafah refugee camp in the southern Gaza Strip, where I would enter via a tunnel some 45 years later.

It was less than a week after the Six-Day War when an Israeli army officer showed up at the Rafah Camp with a company of soldiers and a bulldozer. The unit commander ordered everyone out of their homes. Then he sent the women and children under 13 years of age back into their homes. The others he brought to another part of the camp, where the soldiers lined them up against a wall and shot them. Next the officer went and shot each one again in the head, more than 30 of them, including a 13-year-old boy and an 86-year-old man. Then he had the bulldozer run over the bodies until they were unrecognizable.

The victims were all relatives of the late Abu Ali Shahin, who passed away in Gaza in June of this year. He was a Fatah commander who spent close to 20 years in Israeli prisons. In late 2010, I had the opportunity to meet this revered Palestinian leader. I was told that he was the man who created the order that guided the lives of thousands of Palestinians in prison. And, I was told, he had a lot of respect for my father and, he wanted to see me.

So, I went to Ramallah where a diminutive old man with white hair, glasses, and a white beard welcomed me with hugs and kisses. He told me it was the first time he spoke in Hebrew since 1982, and he went on to tell me about the massacre in 1967 of his entire family. Then, he looked at me and said: “That is how I know your father.” Apparently my father had heard of the massacre and went to investigate for himself. Abu Ali continued:

Everyone in Rafah talked about the fact that Matti Peled, one of the greatest officers of the Israeli army, a general that was highly respected, straight as an arrow, the man who was military governor of Gaza, came in person, he even drove himself, and visited the homes of the victims. Your father visited my family’s home, he spoke to the adults and he consoled the children. People commented how disturbed he was when they took him to see the spot where the massacre took place… It became known that this changed him from a militant man to a man dedicated to peace. I felt your father was with us and that washed away the anger in my heart completely. Completely!

When I returned home to Israel, I told my mother about my meeting with Abu Ali Shahin.

“Yes,” she said, “ I remember this. Your father was so upset he couldn’t sleep for weeks. He wrote to (IDF Chief of Staff) Rabin and to (Deputy Chief of Staff) Haim Bar-Lev about it, but they did nothing. This event changed him completely.”

I would like Americans

to know what U.N. General

Assembly Resolution 3103

of 1973 says.

In 1971, Ariel Sharon returned to Gaza, now as commander of Israel’s southern front. Sharon and his troops conducted a seven month long operation inside Gaza, to “cleanse” it of terrorist cells. Hundreds of Gazan residents were killed, countless others were wounded and hundreds more imprisoned.

All of this amounts to little more than the tip of the iceberg of what Israel has done in Gaza over the last six decades. The attacks increased in numbers and in volume.

The worst attack so far commenced on the Jewish holiday of Hanukah, in 2008, and lasted for three weeks. According to the Israeli ambassador in Washington Michael Oren, the code name “Cast Lead,” given to this attack, was taken from a line in a well-known Hebrew nursery rhyme about Hanukah.

It is worth paying close attention to the terms with which Ambassador Oren described and justified the Gaza assault of December 2008 in a lecture that he gave at Georgetown University in February 2009.

Quoting President Dwight Eisenhower he referred to the assault as “the fury of an aroused democracy.” He stated that when Israeli air force jets dropped hundreds of tons of bombs on a civilian population in Gaza it was a “stunning air attack” that “killed 200 people in the first four minutes.” 2,000 raids were carried out in six days, according to Oren. For the Israeli air force pilots this was like shooting fish in a barrel, as there are no air defenses in Gaza.

In his attempt to further defend the attacks Oren said, “Sacrificing the element of surprise, Israeli planes leafleted the areas targeted for strikes.” But he later admitted, when pressed during the Q & A, that there is nowhere to hide in Gaza. While it’s true that they dropped thousands of leaflets to let the besieged people of Gaza know that this nightmare was about to begin, it’s also true that a mother or father who saw the warnings, knowing that death and destruction were pending, also knew that there was nowhere to go, nowhere to hide the children, nowhere to hide from the fire, the smoke, the chemicals and the white phosphorous that melts the flesh and won’t be extinguished. There was nowhere to go because Israel had imposed a siege, a never-ending lockdown on the people of Gaza.

“On January 3,” Oren continued in his remarks at Georgetown University, “10,000 Israeli ground troops advanced into Gaza. The response to the reserves call up was 100%, ponder that,” he suggested with pride.

Indeed one ought to take a moment to ponder why ten thousand Israeli troops were sent to invade Gaza, a place that never had as much as a tank or a warplane. Ponder what are ten thousand troops to do in such a small and over- crowded place as Gaza? And then ponder the casualty count, over fourteen hundred dead and countless wounded and burned.

United Nations Resolution 3103 states that:

The struggle of peoples under colonial and alien domination and racist regimes for the implementation of their right to self-determination and independence is legitimate and in full accordance with the principles of international law.

Any attempt to suppress the struggle against colonial and alien domination and racist regimes is incompatible with the Charter of the United Nations, the Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Co-operation among States in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples and constitutes a threat to international peace and security.

Certainly, “colonial and alien domination” characterizes Israel by its own admission, and “racist regimes” applies because Israel insists it is a “Jewish” state even though half the population under its control is not Jewish. This means that Palestinian resistance, besides being justified politically and morally, is legal under international law.

Still Israel keeps thousands of Palestinians in its prisons, many without trial and most of whom have not been charged with acts of violence, but rather unarmed, political resistance. Though Palestinian resistance is usually characterized as violent, it has overwhelmingly been unarmed and non-violent.

Today the resistance is taking place on several tracks; e.g., the local armed resistance in Gaza, like the Qassam Brigades, that try to retaliate for Israeli military assaults, and the unarmed marches in the West Bank, that bring together Israeli and international activists who join local Palestinians to protest the occupation of Palestine. They face assaults of tear gas, rubber-coated bullets, and beatings by the Israeli military, as shown in the Oscar-nominated documentary “Five Broken Cameras.”

The movement to boycott, divest and impose sanctions on Israel, BDS, is a form of dedicated, principled resistance that is non-violent and mirrors the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. BDS has had some successful campaigns that have reached millions around the world, from petitions to encourage performers to refrain from performing in Israel, to campaigns against companies that do business with Israel and the boycotting of Israeli products. The BDS campaign has gained several serious supporters like Bishop Desmond Tutu, author Alice Walker, rock star Roger Waters, and, most recently, cosmologist Stephen Hawking and filmmaker Mira Nair.

Further resistance has developed in the U.S., as in other countries in the West, in the form of student organizations. Probably the best known in the U.S. is Students for Justice in Palestine, SJP. Over the last five years or so, this group and others similar to it, have spread across universities and colleges and have made a tremendous contribution to the discussion on the issue. With regular events, protests, and cultural gatherings, such groups are exposing thousands of university students to the Palestinian cause, while often having to face fierce opposition from university administrators and pro-Israeli groups. SJP also has brought about the passing of divestment resolutions in Student Senates on several campuses around the U.S. and Canada.

Online publications such as Electronic Intifada and the Palestine Chronicle, run by Ali Abunimah and Ramzi Baroud respectively, have a far and wide reach and the material they publish is read worldwide. Both give a voice to the Palestinian cause and to alternative views that are otherwise left neglected by a mainstream media that is becoming increasingly irrelevant.

Art, literature and poetry are used as part of this resistance as well. Through reading the works of Palestinian writers, one can fully appreciate the breadth and depth of the Palestinian experience and the scope of what Israelis are missing when they accept the boundaries placed upon them by Zionism. I personally was able to appreciate this once I shed my own Zionist identity.

Susan Abulhawa’s bestseller “Mornings in Jenin,” for example, shocked me with its realistic depiction of Palestine, its people and its history through the story of one family. It, along with novels like Elias Khoury’s “Bab El-Shams,” published in English under the title “Gate of the Sun,” powerfully challenge the Zionist narrative.

Similarly, Ibrahim Nasrallah, one of the finest Arabic writers of our time, has given us “The Time of White Horses,” the story of a single village in Palestine. His account allows us to appreciate the Palestine that was, and the depth of the destruction and pain brought upon a country and a nation by the violent creation of the state of Israel.

I was recently given the book “Hamas: Unwritten Chapters” by Azzam Tamimi. The author himself gave the book to me and, as I look at the cover, I can feel the last remnants of the fear within me. I look at the photos of Hamas leader Ahmed Yassin, murdered by Israel, the crowds of armed men wearing black ski masks and young children held by their mothers, wearing the green Hamas head bands. It all comes back: the years of conditioning to fear the oppressed and their fight against injustice, as well as the years of delegitimizing the calls for justice and equality made by the oppressed even as they are targeted by a combined effort of advanced military technology and brute force.

As always, when the victims of oppression decide to rise against their oppressors, it will fill the oppressors with fear. Yet would we have acted differently? My father said when asked about terrorism: “When a smaller nation is occupied by a larger power, terrorism is the only means at their disposal.” This may or may not be true, but what is certain is that Palestinian resistance will not stop until Palestine is free and democratic.

I would like Americans

to know that the Zionist

claim to exclusivity

can no longer be justified.

A clear and realistic solution to the tragedy in Palestine exists. It is a free and democratic state in all of Mandate Palestine, with equal rights for Israelis and Palestinians, with clearly stated protections for the rights of minorities.

Those who benefit from the status quo will make one of the following claims:

- That a solution can never be found because Jews and Arabs could never live together peacefully in one state. This is aligned with the Zionist claim mentioned earlier that Arab hatred is incurable.

- That discussing the merits of a single democracy is pointless, since the international consensus is for a two-state solution

Both claims are false, misleading, and completely disingenuous.

Prior to the establishment of the Zionist movement, Jewish communities in the Arab world fared far better than Jewish communities in the Christian west.

As for the two-state solution, it was adopted by the state of Israel in 1993 as a strategy whose goal is to strengthen the Israeli hold on all of Palestine. It began with the Oslo accords that led to nothing and it continues to this day with talks about talks that everyone knows are safe for Israel because they will lead to nothing. Israel’s deputy defense minister Danny Danon said as much on June 6, 2013 in an interview in The Times of Israel: “Netanyahu calls for peace talks despite his government’s opposition because he knows Israel will never arrive at an agreement with the Palestinians.” He went on to say that if “there will be a move to promote a two-state solution, you will see forces blocking it within the party and the government.”

The reality is that there is no longer a possibility for a Palestinian state to be established on the West Bank and, as long as the discussion of a two-state solution continues, Israel is free to ignore Palestinian rights and international calls for justice.

Israel has created one state on all of Mandate Palestine, and while this may be a democratic state for Jews, the reality is that close to half the population within the land of Israel is not Jewish. Today Israel governs about 6.5 million people who are Israeli Jews, and 6 million Palestinian-Arabs. The Palestinians, or the “non-Jews” as they are typically categorized in Israel, live under a different set of laws. Israeli Jews enjoy the rule of law and democracy. Palestinians who are Israeli citizens live under a growing number of discriminatory laws (for a list see http://adalah.org/eng/Israeli-Discriminatory-Law-Database), and the Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza have no laws that protect them. They are at the mercy of the Israeli military and other security branches.

Israel is not a homogenous state, it is not a Jewish state, and it is not a democracy.

The Zionist claim to exclusivity can no longer be justified. The world’s indulgence of the Zionist state, largely due to a combination of belief in biblical promises and guilt for the holocaust, needs to end. If anything is to be learned from the history of the Jewish people, both ancient and modern, it is that the application of justice and equal rights is the best guarantee to people’s safety and well being.

Israelis, being the children of colonizers and immigrants have become natives and Palestine is now their homeland too. This is not true for Jews in other countries, who have no right to claim Palestine. While Palestinians will certainly not accept Israelis as masters, one may safely assume they will accept them as equals.

But the past cannot be erased. The bi-national democracy must recognize the right of refugees to return and ensure the release all political prisoners. This new political reality will also move Israelis beyond their current state of fear and militarism. This will mean the end of Zionist dominance in Palestine, the end of the so-called Jewish state, and the beginning of a new era with endless possibilities for both Israelis and Palestinians. ■

Miko Peled’s Link article is based on his book “The General’s Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine,” published in 2012 by Just World Books. Permission to reproduce excerpts contained in the article must be obtained from the publisher (rights@justworld books.com).