By David Sheen

Alleged Assassin of Alex Odeh Finds Safe Harbor in Israel

An independent investigation into the 1985 murder of Palestinian-American activist Alex Odeh has revealed that one of three suspected assassins has been living openly in Israel ever since, hiding in plain sight.

One of the FBI’s suspects, Robert Manning, is currently serving a life sentence in an Arizona jail for another, unrelated murder. A second suspect, Keith Israel Fuchs, has mostly maintained a low profile in a small settlement in the West Bank, steering clear of social media.

But the third suspect has not been hiding in some small corner of the country, working at a mundane trade where the chances of his past catching up to him are remote. Rather, he has remained in the public eye all along, peddling his supremacist ideology, courting controversy, and thumbing his nose at the law – for decades.

On the very day of the attack, October 11, 1985, Andy Green was identified as a suspect in the bombing of the Santa Ana, California offices of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC), where Odeh served as the organization’s regional director for the West Coast. Since that time, for the last thirty-four years, Green has lived in Israel and Israeli-occupied territories under the Hebrew name Baruch Ben Yosef.

In the intervening decades, Ben Yosef earned a law degree from Israel’s Bar-Ilan University and has worked as an attorney out of offices in downtown Jerusalem for a quarter-century. During this period, he has appeared dozens of times in front of Israel’s Supreme Court, defending fellow followers of the late far-right Rabbi Meir Kahane, and filing suits against numerous Israeli ministers and prime ministers, demanding increased rights for Jews, to the detriment of the local Palestinian population.

Ben Yosef is one of the pioneers of Israel’s settlement movement and its modern-day Jewish Templar movement. The Templars seek to supplant the Dome of the Rock – the iconic gold-domed Jerusalem shrine considered the third-holiest site in the world to Muslims – with a temple to Jehovah, in which they intend to mass-sacrifice cattle, over ten thousand on every major Jewish holy day.

Ben Yosef is thought to hold the record for the Jewish citizen who has sat the longest in an Israeli jail under the controversial protocol of administrative detention: once for six months in 1980 with Meir Kahane himself, and again for six months in 1994, together with Kahane’s other top lieutenants. The measure allows Israel to incarcerate suspected terrorists without allowing them to see the evidence against them, and is used almost exclusively against Palestinians.

Retired US law enforcement agents who worked on the Odeh investigation confirmed to this reporter that Ben Yosef, along with two other followers of Kahane, Keith Israel Fuchs and Robert Manning, have been the government’s top suspects. Agents currently working the case also affirmed that the three are still the top suspects in the murder.

Reached for comment on the findings of this investigation, Ben-Yosef said in an email, “I categorically deny any connection to the matters mentioned in your letter,” and would not answer any other questions.

Who Is Andy Green?

Raised in the Bronx, Andy Green immigrated to Israel in February 1976. In interviews, he has recalled being inspired by the Revisionist Zionist movement, which developed into Israel’s ruling Likud party, and by the Jewish Defense League of Rabbi Meir Kahane, who combined the secular Likud’s hardline nationalism with Orthodox Judaism’s religious fundamentalism.

Revisionist Zionists fight for an Israeli state that is dedicated first and foremost to the welfare of its Jewish citizens. But the original Revisionists wanted the character of that state to be secular. Orthodox Jews, on the other hand, have long prayed for a future age in which everyone in the world, Jew and Gentile, would submit to their religious rulebooks. But traditionally, Orthodox rabbis resolved to wait for the arrival of a messiah strong enough to bend the nations of the world to his will; until then, they would remain passive in the Diaspora.

When Kahane fused the two philosophies in the late 1960s, he retained the worst aspects of each, jettisoning the built-in safety valves that prevented either of their worst excesses. Kahane candidly called to turn Israel from a secular ethnocracy into a Jewish theocracy governed by the laws of the Talmud, and to purify the entire Land of Israel of its non-Jewish occupants. And he called on his followers to stop waiting for that Arab-free future to come to pass on its own, but rather for them to do whatever was necessary to make it manifest as soon as possible.

During his lifetime, Kahane openly called for ethnic cleansing and genocide. For decades, in English and Hebrew, in the Knesset and in the streets, from Jerusalem to New York – where he was born, and where he died from an assassin’s bullet in 1990 – Kahane advocated expelling by force Arabs and other non-Jews from Israel and the occupied territories.

On Israeli TV, Green explained the philosophy of his former mentor thus. “He said, I want the goyim [non-Jews] to look at Jews and think they are beasts, that they’re bullies. And be afraid of them.”

Moved by Kahane’s ideas, Green started going by his Hebrew name Baruch, and later adopted the last name Ben Yosef, after Shlomo Ben Yosef, a Jewish immigrant to mandatory Palestine who was sentenced to death by the British for attempting to blow up a busload of Arabs. Upon arriving in Israel, Ben Yosef moved to the West Bank, becoming one of the pioneers of the movement to settle Jews there following Israel’s 1967 conquest of the territory. While he waited to be inducted into the Israeli army, Ben Yosef joined a group of religious Jews and together they established the first Israeli settlement in the northern West Bank, the town of Kedumim, near the Palestinian city of Nablus.

He then joined the Israel Defense Forces in August 1976, serving amongst the last groups of recruits to the elite Shaked commando unit before the army brass disbanded it. After his discharge, Ben Yosef left Kedumim, saying that it had “a leftist leaning to it”, and moved instead to the Hebron-area settlement of Kiryat Arba, a hotbed for followers of Kahane.

In the New York Village Voice and in The False Prophet, his 1990 biography of Kahane, the late investigative journalist Robert I. Friedman chronicled Ben Yosef’s violent adventures following his army discharge.

Friedman notes that in 1978, Ben Yosef was arrested for bombing a Palestinian bus and for conspiring to bomb the offices of Jerusalem’s Arab Student Union. Two years later, then-Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin ordered Kahane and Ben Yosef be placed under administrative detention for six months under a 1945 British colonial law that predated Israel’s establishment in 1948. The law’s application against Ben Yosef and Kahane was its first use against Jews since the earliest days of the state.

In May 2019, Carmi Gillon, the former head of the Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security services, revealed on Israeli TV the reason for Ben Yosef’s incarceration: he had plotted to destroy one of the holiest Muslim shrines in the world.

“Kahane planned, with another member of the group, Baruch Ben Yosef, to shoot a M72LAW rocket at the Dome of the Rock. And he hoped that in the wake of that, all the Muslim states will launch war against Israel. That’s the war of Gog and Magog. And he was arrested under emergency regulations, just like a Hamas terrorist,” Gillon said.

Ben Yosef seemed confident that the winner of such an apocalyptic war would be an Israeli state with far fewer Arabs in its midst. According to an Israeli media report on another Ben Yosef arrest years later, the purpose of the plot he hatched in 1980 had been to “attack Arabs and incite them, until the government would have no choice but to carry out a massive exile of Arabs.” In other words, it was not only an effort to lay waste to a Muslim sanctuary, but also a bid to catalyze an ethnic cleansing.

In August 1983, a 24-year-old Ben Yosef moved back to the United States in order to run Kahane’s New York City operations.

Three months later, in November, Jesse Jackson announced his candidacy for leadership of the Democratic party. The move made Jackson, a former disciple of Martin Luther King Jr., the first African American man to run a country-wide campaign for the US presidency. Kahane and Ben Yosef interrupted the launch with shouts of “racist anti-semite” and “enemy of our people”, and were arrested and charged with disorderly conduct.

Kahane and Ben Yosef targeted Jackson because he had met with the PLO’s Yasser Arafat as early as 1979, and called on the US government to engage him in dialogue, when the PLO was still a guerilla group. Jackson had advocated for the Palestinian cause when it lacked legitimacy in Washington; another decade would pass before US President Bill Clinton hosted Arafat at the White House, where he signed a peace treaty with Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in September 1993.

While Jackson’s campaign for the US presidency was effectively torpedoed, Kahane returned to Israel to compete in national elections for the fourth time, and in July 1984, after a decade of failed attempts, he achieved his goal, earning himself a single seat in the Knesset. Just as Kahane’s campaigning in Israel finally bore fruit, Ben Yosef chose to remain in the US.

That year, Alex Odeh and other ADC staffers began to receive menacing telegrams and phone calls from a public payphone near the Jewish Defense League’s LA office. They were from people who claimed to be with the JDL. Those violent threats would soon be carried out.

The ADC had been founded in 1980 to counter media smears against the Arab community, and to lobby for their interests. Those interests included curtailing the billions of dollars in annual aid money that the US government gives to the Israeli military. By 1985, the ADC was taking out full-page adverts in major US papers, calling to keep those funds in the USA.

That activism made the ADC enemies of the Kahanists, but also of the pro-Israel lobby group AIPAC, and of another powerful group that the ADC once saw as their Jewish corollary: the Anti-Defamation League. For a decade, the ADL had published reports on Arab-American organizations, calling them a “propaganda apparatus” and accusing them of being either “PLO fronts” or “part of the Arab master plan”.

The anti-Arab campaigns of AIPAC and the ADL successfully stripped communal voices like the ADC of their legitimacy; so much so that US campaign donations from Arab-Americans were regularly returned to their donors by local, state and federal politicians – including, just the previous year, the Democratic candidate for US President, Walter Mondale.

But the Kahanists believed that Arab-American voices should not only be politically excluded, but physically silenced, as well.

Exactly half a year before the attack on Odeh, the head of the Jewish Defense Organization, a JDL spinoff faction, managed to track down the ADC’s office in New York City even before its opening had been announced to the group’s own members. In the weeks and months that followed, unknown thugs attempted to break into the office and sprayed the word “ragheads” outside the office entrance. Crank calls from individuals identifying as the “Jewish Defense League” quickly became commonplace. “Listen well you PLO scum,” said one caller on the ADC’s answering machine. “Sabra and Shatilla are going to seem like nothing in comparison to what we’re going to do to you Palestinians.”

As Robert Friedman recorded, Amihai Paglin, the Jewish terrorist who had orchestrated the 1946 bombing of Jerusalem’s King David Hotel, had been training JDL members in bombcraft since at least the early 1970’s. But with Baruch Ben Yosef back in the US, Kahane’s henchmen could now also depend upon the tactical expertise he had picked up during his service in the now-defunct Israeli commando unit Shaked.

A JDL plot to assassinate James Abourezk, the first Arab-American Senator who founded the ADC, was uncovered and foiled by the FBI. But in the second half of 1985, ADC offices on both coasts were bombed, and the perpetrators were thought to be Jewish terrorists inspired by Kahane, who had held rowdy protests outside the group’s Washington, DC headquarters.

On the East coast, a police officer suffered ghastly injuries, incurred while attempting to disable a pipe bomb planted at the ADC offices in Boston on 16 August 1985. Randy LaMattina lost all of his original teeth and his career with the Boston Police Department that day; his fingers, ripped to shreds by the bomb, still do not have feeling in them.

On the West coast, seven people were injured and Alex Odeh lost his life when a bomb exploded as he entered the ADC offices in Santa Ana, California on 11 October 1985.

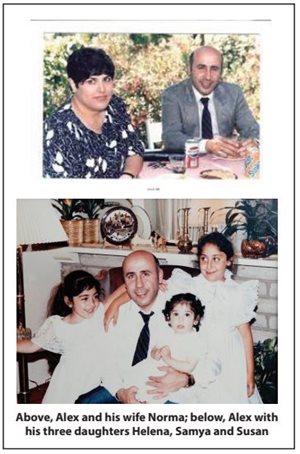

“I was afraid. I wanted him to quit the ADC,” Odeh’s widow Norma Odeh told Robert Friedman. “I told Alex the JDL would kill him, and they did.”

When Odeh’s body was buried on October 15, security for the service at St. Norbert’s was especially tight, since the church had received multiple bomb threats.

But the official JDL leadership did not wait for Odeh’s body to be buried before they began to smear his memory. “I have no tears for Mr. Odeh,” said JDL national chair Irv Rubin. “He got exactly what he deserved.”

As for the perpetrators of the crime, “the person or persons responsible for the bombing deserve our praise,” Rubin added.

When the city of Santa Ana erected a statue of Odeh to honor his legacy, on what would have been his fiftieth birthday, Rubin appeared on the scene, approached Odeh’s daughter Helena and issued the same gruesome message.

“He started walking in my direction,” Helena recalled on the 34th anniversary of her father’s murder, “looked me straight in the face and told me my father deserved to die.”

Her voice welled up with tears as if she was reliving that very moment. “My dad missed out on everything, he missed out on seeing his daughters, he missed out on his grandchildren,” she said. “How can somebody have that much hate in their heart?”

Alex Odeh

Alex Odeh was born in the West Bank village of Jifna in 1944, when the land was called Palestine and the military rulers were British. After studying in Egypt and then immigrating to the United States, Odeh was hired by the ADC to speak up for Arab-Americans, Muslims and Middle Easterners in general, who were then maligned in the media at least as much as they are today, if not more.

Odeh came from a Christian family, but he aspired to see peace in Palestine for all its inhabitants, Muslims, Christians, Jews, and others. In fact, he was scheduled to speak at a local Reform synagogue, Congregation B’nai Tzedek, on the very day that he was murdered. And his calls for compromise were not just virtue signaling or political posturing; Odeh had openly advocated for a two-state solution in the Holy Land years before the PLO adopted partition as its official policy.

But as he told Robert Friedman, Baruch Ben Yosef did not share that vision of peace. “The Arabs have no claim to the land. It’s our land, absolutely. It says so in the Bible. It’s something that can’t be argued. That’s why I see no reason to sit down and talk to the Arabs about competing claims. Whoever is stronger will get the land,” said Ben Yosef.

In a Village Voice article by Friedman published a month after Odeh’s assassination, Ben Yosef insisted upon the right to bomb Palestinian civilians to death. “[Zionist militia] Irgun leader David Raziel planted a bomb in an Arab market in 1939, killing 15 or 20 Arabs,” said Ben Yosef. “And do you know how many streets are named after Raziel in Israel? If it was alright for him, how come it’s not alright for us?”

If Ben Yosef’s justification is sickening, his argument is still sound; in addition to numerous streets, Israel has also named a school, and even a settlement, after Raziel.

Now this logic legitimizing lethal violence against Palestinians was being imported to the US half a century later. From the perspective of ADC co-founder and attorney Abdeen Jabara, the timing of the Odeh assassination was not coincidental; it occurred just when Arab Americans had begun to assert themselves as active participants in US politics.

“That violence is intended to chill the exercise of the constitutional rights of Arab-Americans,” Jabara told the US House Subcommittee on Criminal Justice on 16 July 1986, nine months after the Odeh murder. “That violence is intended to stop a nascent voice, because Arab-Americans began to organize themselves, for the first time to play a role in this society with their fellow Americans, standing shoulder to shoulder in the marches for jobs, peace, and justice, in the corridors of power, and because of that they have been targeted for attack.”

At the same House hearing, another ADC co-founder noted that the physical attacks against the ADC from the Jewish Defense League had been preceded by negative PR offensive by other, more mainstream, Jewish groups.

“The campaigns of vilification and the violence against Arab American organizations and leaders fit into a coherent pattern, and the sources of both the vilification and the violence can be seen as sharing a common political agenda,” said James Zogby. “I am not suggesting that AIPAC, the ADL and the JDL are collaborators. They do, however, share a common political agenda, and their tactics in fact converge to create a personal and a political threat to the civil rights of Arab Americans and their organizations.”

When Zogby made those remarks, fresh in his mind must have been a three-month-old incident that left him embittered towards the ADL. Per Zogby’s description, two ADL leaders had visited a Democratic Party chapter chair in upstate New York and urged him not to endorse Zogby for State Assemblyman, alleging the latter was a “Libyan agent”.

But Zogby was correct in noting that ADL and JDL campaigns were consistently converging on shared targets. A decade previous, in 1976, a JDL front group called SOIL (Save Our Israel Land) had attacked a dozen New York City banks – firebombing some and smashing windows of others – just days after the ADL announced that those banks didn’t conduct business in Israel. And now the ADL’s smears against the ADC had been followed by the JDL’s fatal attack on Alex Odeh.

To be fair, it is unlikely that Kahanists would have needed any tailwind support from conservative community groups to convince them to eliminate an outspoken Palestinian-American activist.

Likewise, it is also unlikely that a trained JDL cell motivated to murder Odeh would have needed any outside intelligence in order to carry out that task. If they had required such sensitive information, however, it could have been provided; at the time, the ADL’s top spy Roy Bullock had infiltrated the Arab-American Anti-Discrimination Committee, and had even obtained a floor plan and a key to Alex Odeh’s office.

Years later, when the FBI realized the vast extent of the ADL’s spy operations – which included information on hundreds of US groups and over ten thousand US citizens – Bullock denied any involvement in the Odeh murder, but admitted that among the dozens of groups he had infiltrated on behalf of the ADL were both the San Francisco and Los Angeles-area offices of the ADC.

“The Bureau was interested — they had traced the three or four guys they thought did it,” Bullock told the San Francisco Police Department in January 1993 about the FBI’s investigation into the Odeh murder. “I missed going to the office by one day; I might have been there to open the door instead of him because he allowed me to go into the office if I was down there; just by sheer coincidence it wasn’t me.”

As an ADL agent posing as a solidarity activist volunteering with the ADC, Bullock amassed information on thousands of the group’s members and tried to recruit suspected anti-Semites into the ADC in an attempt to discredit it.

“He was one of our most vocal members,” ADC President Albert Mokhiber said of Bullock after his espionage became public knowledge. “He portrayed himself as someone sincerely interested in Arab civil rights and someone dedicated to the principles of our organization, and everyone believed him to be so.”

The full extent of the ADL spy saga will likely never be known; in 1993, the year that the scandal broke, Project Censored named it one of the year’s most censored stories.

Despite the extent of its colossal spy apparatus, the ADL never chose to turn its sights on the reactionary factions it would have been best positioned to infiltrate: violent Jewish groups like the JDL.

“The League doesn’t officially investigate the JDL, it just isn’t something they do,” Bullock explained to the SFPD. “They have written one special report denouncing them, as inflammatory bigots and zealots, but they don’t officially launch investigations against them.”

Like other conservative community organizations, the ADL condemned fanatical Jewish groups in public, but cooperated with them in private when they shared objectives. In 1986, long-time ADL spymaster Irwin Suall admitted to the Washington Post that he regularly traded information with Mordechai Levy, the leader of the JDL splinter group JDO. Levy’s JDO had harassed, defaced and menaced the ADC’s offices in the run-up to the Odeh assassination, and Levy himself continued to distribute an “Enemies of the Jewish People” list which included on it the ADC, even in the weeks following Odeh’s murder.

Extradition

In the years that immediately followed Alex Odeh’s murder, the fortunes of the Kahanist movement took a nosedive. In advance of Israel’s 1988 national elections, polls predicted Kahane to sweep into the parliament with up to twelve seats, a result which would certainly have earned him a ministry post. In October of that year, however, the Knesset disqualified Kahane’s Kach party from the running, on account of his unabashed racism.

In November 1990, Kahane himself was assassinated in New York City by a Muslim militant, in what, years later, some would claim to be the first attack by the group that would ultimately come to be known as Al Qaeda. At his funeral, one of the largest in Israel’s history, Kahane was passionately eulogized by Israel’s then-Chief Rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu.

Four months later, Kahane’s loyal followers Robert and Rochelle Manning were arrested at their home in Kiryat Arba. Although Manning was also suspected of involvement in Odeh’s assassination, he and his wife were only indicted for another murder-for-hire, unrelated to their supremacist beliefs.

It had taken years to secure the arrest of the Mannings for that 1980 murder, in part because of a 1978 Israeli law which severely restricted the conditions under which a citizen could be extradited. On the day it passed, that law’s sponsor urged the Israeli parliament to protect not only citizens who had committed crimes while travelling abroad, but also foreign-born Jewish criminals who might flee to Israel and receive citizenship upon their arrival, by virtue of their ethnic origin.

“Recall the case of Zeller, whose extradition was requested by the United States over the accusation of murder,” said David Glass, then chair of the Knesset’s Constitution, Law and Justice Committee. Jerome Zeller, another American-born follower of Meir Kahane, was accused of planting a bomb in the Manhattan offices of the legendary arts impresario Sol Hurok in 1972, killing Hurok’s 27-year-old Jewish secretary, Iris Kones. “The State of Israel, via the Justice Ministry, asked to delay extradition proceedings due to the circumstances of the case,” said Glass.

Hurok had promoted performances of the Bolshoi Ballet and other Russian art ensembles, and this had raised the ire of Kahanists, who demanded a blanket boycott on all things Soviet, until the USSR would agree to let its Jewish citizens emigrate. In the Knesset plenum on January 3, 1978, Glass argued that the Israeli government had acted correctly when it had given Zeller safe harbor five years earlier, citing a biblical passage from the Book of Deuteronomy which forbids the returning of escaped slaves to their former masters.

“He is an Israeli citizen, but he committed the crime before he was an Israeli citizen. Do you think that Zeller would have received a just trial, taking into account all the special circumstances of the incident, even in New York or in Los Angeles?”

Zeller is believed to have lived in the settlements since 1972, evading any legal consequences for the death of Iris Kones.

Two decades later, however, in 1992, Robert and Rochelle Manning came up for extradition. Seemingly certain that he faced no serious legal risks himself, Baruch Ben Yosef did not hesitate to lead local efforts to thwart the Mannings’ extradition.

“I’ve been very involved with the anti-extradition program. There’s the Manning case, where we’ve been trying to fight the extradition of the Manning couple, residents of Kiryat Arba. Last year we organized a demonstration. We succeeded in getting almost every rabbi connected with the Rabbi Kook movement and the settlement rabbis to sign a letter calling for the cessation of the extradition,” Ben Yosef told a conference of far-right Anglophones at that time, praising the Mannings as Jewish heroes.

“Here we have the opportunity to stop the extradition of Jews who have been fighting for the Jewish people for the last twenty years!” he exclaimed.

Carmi Gillon, who headed Israel’s Shin Bet and was the organization’s first department chief to be tasked with tackling Jewish domestic terrorism, told this reporter that he recalls monitoring the movements of Manning, and remembers Ben Yosef for his ultra-nationalist activities. But Gillon says that he never knew that the two were suspected of having committed mortal crimes in the US in 1985.

“I really don’t know about that. On my life. I’m hearing it for the first time, from you,” Gillon told this reporter in late 2019. “I never heard of it. I didn’t know that Baruch Green ever returned to the US.”

Moreover, Gillon claims, even if the FBI had asked the Shin Bet for intelligence on Ben Yosef, Fuchs and Manning, it would not have been forthcoming. “Israel worked very well with the Americans since the time of Khrushchev in the 1950s. But there were issues that were taboo. Israel never transferred information about Jews, like the JDL,“ said Gillon.

“There was no cooperation on Jewish issues,” Gillon affirms. “During my time, there was no cooperation at all.”

The Kahanists

In September 1993, the Israeli government reversed its long-standing policy to never negotiate with the Palestine Liberation Organization, and signed a peace treaty with its chairman, Yasser Arafat. The framework of those Oslo Accords provided for the establishment of a Palestinian police force that would maintain law and order in the West Bank and Gaza.

Unsurprisingly, Kahane’s followers poured scorn over the peace treaty, and vowed that they would shoot the newly-deputized Palestinian police officers on sight. “We can’t share the land,” Ben Yosef told the same Los Angeles Times that had just three years earlier reported the murder allegations against him, as Andy Green. “They will run like dogs when the time comes. And we would like to take revenge too. Revenge is a godly idea, and they deserve it.”

Months later, another American-born Kahanist would carry out the most murderous attack in the movement’s history. On February 25, 1994 – a Jumu’ah prayer day during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan – Dr. Baruch Goldstein walked into a West Bank mosque and murdered Palestinians in prayer.

Goldstein, who had run for a Knesset seat in 1984 with Kahane’s Kach party, entered the Cave of the Patriarchs, a Hebron shrine revered by both Jews and Muslims, and gunned down 29 Palestinian men and boys, wounding 125 more. Goldstein’s slaughter took place on Purim, a Jewish holiday that glorifies a mythical slaughter of Israel’s enemies.

In the wake of the massacre, the Kach party and one of its offshoots, Kahane Chai, were declared illegal in Israel, and Ben Yosef was once again jailed under administrative detention, this time with other top Kahanist leaders. But Ben-Yosef’s incarceration would last the longest, and restrictions placed upon him following his eventual release were the harshest.

Years later, Ben Yosef recalled the incarceration of the Kahanist leadership as a “privilege”. “We were in HaSharon Prison together, after our friend Baruch Goldstein cleaned out the cave, the Cave of the Patriarchs, from the garbage there,” he says, describing scores of unarmed men and boys shot while kneeling in prayer. “We were together for the Passover Seder, it was a very special Passover Seder. The greatest of the generation.”

Ben Yosef breaks out into a laugh. “We planned the revolt!”

Last year, a few weeks before the twenty-fifth anniversary of the massacre, videos of Ben Yosef praising Goldstein in Hebrew and English were uploaded to Youtube.

Every year on the anniversary of the horrific massacre, Ben Yosef listens to the reading of the Purim Megilla at the tomb of the mass murderer Baruch Goldstein in Kiryat Arba, a short distance from the scene of his vile crime. In December 2019, the Israeli government began renovating the public park named after Rabbi Meir Kahane, where the tomb is located.

On the same day, Israel’s Defense Minister Naftali Bennett announced that Hebron’s former fruit and vegetable market, which has been boarded up and devoid of Palestinians ever since the 1994 massacre, will soon be rebuilt as a new Jewish neighborhood, in order to double the number of Israeli settlers in the city.

In the years following the Hebron massacre, Ben Yosef defended in Israeli court Netanel Ozeri, the Kahanist author of “Baruch HaGever,” a collection of essays heaping praises upon the mass-murderer Goldstein. Ben Yosef describes Ozeri as Kahane’s top student, who not only recorded Kahane’s speeches and published his writings, but also developed strategies and tactics that were then used by Jewish settlers to expand Israeli control over increasingly large swaths of Palestinian territory. “He in fact became what some people think is the father of the hilltop youth,” Ben Yosef said, referring to the settler strike force of the millennial generation.

If Ozeri was the father of the hilltop youth, Ben Yosef could be considered their uncle, passing on the skill sets he’d developed over time to avoid criminal conviction. In the years that followed his second administrative detention, Ben Yosef served as an instructor at the West Bank settlement summer camp “Fort Judea”, teaching a new generation of young Kahanists how to resist the interrogation tactics of the Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security services.

Over the course of his legal career, Ben Yosef would also argue one of the most infamous cases of Israeli law, representing the man who would go on to become the leader of the reconstituted Kahanist camp, Itamar Ben Gvir.

While Ben Yosef and the rest of the Kahanist leadership were jailed under administrative detention, Ben Gvir, then all of 17 years old, stepped up to lead the movement in their absence.

In 1995, Ben Gvir appeared on a political talk show on Israeli state television, arguing against peace talks with Palestinians, and defending the views of his hero, Meir Kahane. On live TV, Israeli journalist Amnon Dankner, later editor-in-chief of the national newspaper Ma’ariv – said “Kahane was a Nazi” and called Ben Gvir “that little Nazi”. When Ben Gvir sued Dankner for slander, his legal counsel was Baruch Ben Yosef.

The case dragged through the courts for over a decade, and the suit was finally settled by Israel’s Supreme Court in November 2006. The High Court ended the legal saga by affirming the 2002 ruling of the Jerusalem Magistrate’s Court, which found that Dankner had indeed libeled the Kahanist Ben Gvir.

However, because there was “a similarity of ideas in the teachings Ben Gvir believes in and those of the Nazis,” the judge only obliged Dankner to pay damages of a single Israeli shekel – the equivalent of an American quarter-dollar.

As Ben Gvir took his libel lawsuit to the High Court, his mentor Baruch Ben Yosef recused himself from the case to focus on opposing the proposal of Prime Minister Ariel Sharon to disengage unilaterally from the Gaza Strip. By removing the eight thousand Jewish settlers and the Israeli army units protecting them from Gaza, Sharon could claim that Israel’s occupation had ended, and subtract from the state’s population registry the strip’s Palestinian citizens, whose numbers then totaled almost a million and a half. At the time, a majority of Israeli Jews agreed with him that maintaining Jewish numerical superiority in the territories the country controlled directly was worth the cost: ceding sovereignty over a sandy strip of land smaller than 150 square miles in size.

But a significant number of Zionists vociferously oppose retreating from any terrain conquered by Israel, as a refutation of their Biblical blueprint to institute religious rule over all of God’s holy land.

In the summer of 2004, Ben Yosef and other Kahanists ran a camp to train Gaza Strip settlers to forcefully resist the planned withdrawal. “The resistance will be proportional to the force exerted against us,” Ben Yosef told AFP. “If it’s verbal, we’ll answer with words, if we’re hit with sticks, we’ll use sticks, and no one will take guns, but if we’re shot, we’ll shoot back.”

At the time, Israel’s Internal Security Minister didn’t only fear that the Gaza Strip settlers would physically resist when Israeli soldiers were sent in to evict them. He was also worried that far-right activists would attack the Muslim holy sites in Jerusalem in an attempt to derail the project.

Such a scheme would not have been unprecedented in Israeli history. When the Israeli government agreed to return the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt a quarter-century earlier, a group of Jewish settlers started conspiring to blow up Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock, knowing it would outrage Muslims around the world, and believing the fragile peace deal with Egypt would likely collapse as a result, and the planned Sinai withdrawal along with it.

That plot was never carried out, but as Israel prepared for another withdrawal on its western flank, its security establishment estimated that a similar plan to attack the Al Aqsa compound may have been in the offing. Among the scenarios they considered were aerial attacks on the Haram Al-Sharif, from either a kamikaze pilot flying a light aircraft or a drone loaded with explosives.

In late July 2004, Israel’s Internal Security Minister Tsachi HaNegbi told a television interviewer he feared the far-right was now discussing such strategies not only in a philosophical sense, but in practical terms, too. “There is a danger that they’ll want to make use of the most sensitive site and then hope that the chain reaction will lead to the collapse of the political process.”

Three days later, Baruch Ben Yosef dispatched an angry letter to HaNegbi, demanding that he apologize for alleging that Templar activists such as himself were a security threat to the state. Ben Yosef added that if HaNegbi failed to atone for misspeaking, he could expect a protest campaign against him.

Two weeks later, Ben Yosef, his protégé Itamar Ben Gvir, and a dozen other Kahanists organized a protest outside HaNegbi’s home in the town of Mevaseret Zion, where former Shin Bet chief Carmi Gillon had not long before been elected mayor. After the protest went on for some time, an armored vehicle pulled up to the house, and HaNegbi emerged. Instead of retreating into the protection of his home, HaNegbi immediately approached Ben Gvir and extended his hand to wish him well, for having gotten engaged the previous week. “I understand that congratulations are in order,” he said, and explained that he wanted to talk.

“You want to shut the mouths of people who were basically your students,” charged Ben Gvir, accusing him of preparing the public for administrative detentions and other draconian measures against them and others protesting the planned Gaza pullout.

Calling Ben Yosef and Ben Gvir students of HaNegbi was no exaggeration. In the early 1980’s, HaNegbi had been a prominent far-right activist leading the resistance to Israel’s pullout from the Egyptian Sinai, along with hard-core Kahanists. A decade earlier, HaNegbi was in fact one of the first Israeli students at the school Rabbi Meir Kahane established in downtown Jerusalem to spread his reactionary version of Zionism.

HaNegbi sat down and spoke with the activists, and according to one Israeli press report, promised them that the government would not rubber-stamp any detention requests from the Shin Bet.

The “HaNegbi-Ben Gvir Barbecue”, as that Israeli outlet described it, elicited an angry response from liberal activists at Peace Now. “We remind Minister HaNegbi that the Kach organization was made illegal,” said the group in a statement, calling on him to quash the group’s activities, “instead of sitting and chatting with its activists.”

Press photos of the protest-turned-pow-wow showing HaNegbi casually conversing with Ben Yosef and Ben Gvir outside his home were used by the Kahanist movement to make the argument that they couldn’t possibly represent real security threats. “It would be like the director of the FBI accusing a group of trying to blow up the White House and then just strolling out of his house to chat with them,” said Mike Guzofksy, a top Kahane movement activist.

The Aramaic Curse

That fall, at the annual memorial service to Meir Kahane, Ben Yosef denounced Israel’s planned disengagement from Gaza, and called instead for holy war.

“What will bring redemption is war. But today we’re going in exactly the opposite direction,” said Ben Yosef, in a clip that was later broadcast on PBS in an episode of Frontline entitled ‘Israel’s Next War?’. “There’s an attempt to prevent war, at all costs. And if we can force the army to go back to being offensive, an army of revenge, an army which cares about Jews more than anybody else, then we’ll be able to bring the final redemption, in the only way possible: through war. War now.”

Ben Yosef was among the Israelis filmed that year loudly protesting Sharon’s planned withdrawal from the strip, chanting, “Hang the traitors! Gaza for the Jews!”

Soon he started to make it personal. At one such anti-pullout protest outside the Knesset that featured a crowd of thousands, Ben Yosef taunted Sharon with the suggestion that he would soon join his late wife in the grave. “Sharon, Lily is waiting for you,” he said, grinning.

In September, Israeli media outlets published threats by Ben Yosef to perform a medieval curse of death upon Prime Minister Sharon, unless he agreed to cancel the government order to evacuate Jewish settlements and settlers from the Gaza Strip, then occupied throughout its interior by the Israeli army.

The following summer, Ben Yosef made good on his threat. On July 26, 2005, twenty days before the Israeli army’s deadline to Jewish settlers to willingly evacuate the Strip, Ben Yosef accompanied fellow Kahanist leader Rabbi Yosef Dayan and performed the Pulsa Dinura death curse.

Dayan had levied the same Aramaic curse against then-Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin a decade earlier, in an attempt to sabotage the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. On the eve of Yom Kippur in 1995, Kahanists gathered outside Rabin’s residence and wished the worst on him: “All the curses of the world must rain down on him, he must eat his excrement and drink his urine.”

One month later, on 4 November 1995, Rabin was shot to death at a pro-peace rally in Tel Aviv, assassinated by another far-right Israeli who had studied law at Baruch Ben Yosef’s alma mater, Bar Ilan University.

If Dayan’s first curse seemingly succeeded, supernaturally slaying Rabin and knocking the peace process off course, perhaps another Pulsa Dinura from Dayan could sideline Sharon and put the kibosh on his planned pullout from Gaza?

This time, the curse would be conducted at the old Jewish cemetery in Rosh Pina in the Upper Galilee, at the grave of Shlomo Ben Yosef, hung by the British for attempting to blow up a bus full of Palestinians in 1938, and whose surname Andy Green adopted as his own.

“We read the Pulsa Dinura prayer so God will take the murderous dictator who is murdering the Jewish nation,” Ben Yosef told Israel’s highest-selling newspaper Yediot Ahronot after taking part in the Kabbalistic ritual.

“We hope that God will take him from us,” said Ben Yosef. “We called upon angels of terror.”

In response to a query from Yediot, Israel’s Justice Ministry stated that “after listening to and reading about the matter, [it] will consider whether to open a criminal investigation against those involved in the ceremony.”

Five months later, on January 4, 2006, Sharon suddenly suffered a debilitating stroke, putting him in a vegetative state that would last for eight years.

Two days after Sharon passed, the Jerusalem Post published an article entitled “Extremists boast they cursed Sharon,” quoting Baruch Ben Yosef taking credit for Sharon falling gravely ill.

“I take full responsibility for what happened,” Ben-Yosef told the Post. “Our Pulsa Denura kicked in. Nothing could kill Sharon, and he said his ancestors lived until they were over 100 years old, but we got him with the Pulsa Denura.”

The article, authored by Yaakov Katz – now the Jerusalem Post’s Editor-in-Chief – also cites Ben Yosef’s successor as chief Kahanist litigator, Itamar Ben Gvir.

“There is a judge in this world,” Ben-Gvir told Katz. “Yitzhak Rabin was killed on the fifth anniversary of Meir Kahane’s murder and Sharon fell ill on the anniversary of Binyamin Kahane’s murder.” The latter is a reference to Meir Kahane’s second son, who had in fact been murdered five years earlier.

When Sharon finally slipped out of his coma and died eight years later in 2014, Ben Yosef and Ben Gvir offered free legal services to any Israeli Jew charged with celebrating his passing.

What Next?

Immigrating to Israel from the Bronx and transforming himself into Baruch Ben Yosef, Andy Green became the vanguard of the violently racist Kahane movement. The parliamentary records of both the US Congress and the Israeli Knesset have documented Ben Yosef’s supremacist activities. Various mainstream media outlets have reported that he is a suspect in the murder of the Palestine-born American citizen Alex Odeh. Numerous US law enforcement officials past and present have affirmed to this reporter that this is still the case, even today.

And yet Ben Yosef continues to live openly in occupied Palestinian territory, arguing in Israel’s highest courts for a Jewish takeover of the country’s holiest Islamic shrines, and openly advocating for an ethnic cleansing of the country’s Arabs.

More than this: he is regularly interviewed in Israeli newspapers and on prime-time Israeli television, identified as a long-time leader of the Kahanist movement. In the last thirty years, the Israeli press has often covered Ben Yosef’s far-right activism, but in all that time has not once mentioned the American allegations against him.

If Alex Odeh had never been assassinated and instead lived out his days in good health, he would now be 76 years old and surrounded by his family and friends.

Instead, 61-year-old Baruch Ben Yosef is celebrating more than three decades of impunity for his alleged crimes, and the knowledge that the Kahane movement he has served for his whole adult life is on the road to returning to the corridors of political power, under the leadership of his protégé, Itamar Ben Gvir.

These successes are in no small measure thanks to the guiding hand of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who has labored to rehabilitate the Kahanist camp. In the last election cycle, Netanyahu’s support included offering Jewish Power party leader Ben Gvir an ambassadorship and a promise to change Israeli law to permit Israel’s most notorious racists to run alongside him. “Years ago he wouldn’t have done something like that,” Ben Yosef told Israeli TV of Netanyahu’s newfound embrace of Kahanism. “Maybe the demon isn’t so scary now.”

Affirming that the Kahanist movement is now mainstream, former Shin Bet chief Carmi Gilon envisions Kahane himself looking on from the next world, pleased as punch. “I think that today he is not spinning in his grave. He’s lying in his grave, sees what’s happening in Israeli politics, and says, ‘Hell yeah! I did it!’” ■