| Also in this issue: In Appreciation: Donald Neff, 1930-2015 |

By Rawan Yaghi

w a v e s

The waves were high enough to swallow the whole city. He stood there and stared at them with his lazy heavy eyelids. It did not matter if the waves crashed on top of his small body. That image stirred nothing inside him.

As the wave progressed in that empty space and time, it seemed like he was watching a screen in the large blue wall that marched against the city.

He looked at himself in the wave, still a boy of five, intently listening to the incessant explosions all around his neighborhood. They marched closer and closer every hour. His mother’s worry was very obvious to him though she tried to hide it. Every time the sound went louder, she looked at his father imploringly.

“We have to leave. Now.” Ahmed heard her tell his father in their bedroom.

“Where do you want us to go? They’re bombing everywhere. We can’t be safer than in our own home. They will bomb us the moment we step out the door.”

It went on like that for three days. He was forbidden from going out of the house to play with his neighbors. He was not allowed to look out the window. Sometimes, going to the bathroom alone seemed like a dangerous undertaking.

“Mum, are there people in the planes?”

She stared at him for a moment. How to explain murder to a five-year-old?

“Nobody, habibi. Nobody at all.”

“But the radio guy says they are Israeli military planes. Does that mean there are Israelis or military in them? What’s military?”

She sighed and shifted over a few inches towards him, wrapping him with her arms. “Nobody is in the planes, hamoody. They’re just not working properly and they’re trying to fix them.”

His muscles relax as she tightened her arms around him pulling him closer to her chest and letting his face rest between her neck and collarbone.

* * *Seven years later, that image of her was so clear in the wave. It was so beautiful that the wave coming to crush his bones was all he wanted. He wanted it to stop there. He did not want his memory to recall anything else that happened after that.

* * *

Two days after that day, the explosions were very loud, and they could hear machine guns firing all through the night and day. Sometimes, the waves of gunshots would sound for a whole hour. Ahmed’s father paced to the door and back constantly. He prepared a broomstick on which he tied a white shirt. His father looked at his mother and asked her to forgive him. He had tried to call an ambulance or somebody to ensure they get out of the area safely, but his phone could not pick up any signal.

Three days later, A bullet came through the eastern window of the living room. So, they decided to move west to Ahmed’s bedroom.

They were very careful. Nobody was allowed to stand up. They had gotten used to crawling to the bathroom which was the only place they allowed themselves to go to.

Nearly the whole time, Ahmed stuck by his mother’s side. He only slept between her arms which clutched to his bones harder that night. His father lay right next to her and held her hand which was above Ahmed’s shoulder. They lay like that the whole night. Ahmed would nod off for a few minutes only to be woken up by another stream of bullets crashing into his ears with the explosions that followed. The time was a mixture of day and night that took turns every hour or so.

He did not know how much time passed before an ambulance came. They banged at the door asking if anybody was inside. His father hesitated for a moment, not sure whether to believe they were actual paramedics or not. He could not risk letting them go. After he shouted back saying they should prove they were Palestinian, a man shouted his own name and where he came from. Ahmed’s father rushed to the door and opened it.

Ahmed was trying to shake his mother awake but she wouldn’t move a muscle. The paramedics hurriedly checked her body and said that there was no room, that she had to stay there. Ahmed held on to her and screamed that they can’t leave her there. His father carried him by the waist as he kicked the air, writhing furiously to release himself from his father’s grip.

His father turned from his mother’s body and headed to the door. The paramedics told them to wait a second at the door. Ahmed was still trying to get out of his father’s arms when the scene outside hit his father. There were a few houses which were still standing but most of the neighborhood was just unrecognisable piles of rubble. He did not know where he was and, for a moment, he was going to let go of his grip around his son’s waist. There was a sound of a helicopter somewhere, but he didn’t have time to process where it was.

“Get the fuck in,” the paramedic’s voice sounded like it was echoing from beyond a mountain. Still screaming, the paramedic ran to the father’s frozen body and started dragging him to the back door of the ambulance. “Get in,” he finally implored him. Ahmed was still kicking which eventually woke his father up from his stupor and made him climb into the ambulance. The paramedic got in and closed the door behind him shouting at the driver to go.

Inside, Ahmed kept screaming, kicking and punching his father’s chest when his father started crying trying to keep Ahmed in his embrace. The paramedic finally gave Ahmed a tranquiliser shot after which he gradually calmed down and fell asleep.

* * *

Under the midday sun, the sea glittered like a golden necklace.

The car moved along the beach. Sometimes the waves were very blue and sometimes you could see the waves heavy with bright plasticky weed. Sometimes his mum sang along with the old song that played out of the speakers installed on the car doors. He remembers her voice, so melodic, easily dancing with the music and following the voice of the singer in the speakers, sometimes forgetting the lyrics and humming along. His dad listened intently too and though he rarely spoke, Ahmed could tell he was enjoying the music and his mother’s singing with it.

He could barely remember the waves looking so clean and he could barely remember his mum. It is as if they were never there. He wondered sometimes, if he was imagining this: being driven in the car by his father along the beach. Were the waves really that clean? Did he really pay attention to their color being so young a child? And how did he remember the song his mum sang along with?

“A thousand nights and one night,” the line kept repeating and repeating until he got bored and begged for it to be changed. Only for his mum to laugh at his impatience and tell him that “one day, you will like this song.”

* * *

Whether he loved the song or absolutely hated it, is still undecided. The song could grab him out of anywhere and push her into his memory. He would be sitting in a cab, on the beach, in the street, in his room. And the song would seep from a radio or a phone and take him away. A few minutes later, he’d come back to where he was, feeling like he was away for hours, wondering if a whole day had gone by.

He couldn’t take it anymore. The song and the sunlight reflecting on the waves made him feel like he was about to lose the tray he was selling snacks off. He dropped it and ran east. He kept running for an hour, passing through the paved streets, the clothes market downtown and the food market a little bit further. He ran, with nobody minding him. He could not see anyone around him. He was knocked down a couple of times, hitting men who came out of nowhere. He would immediately get up and continue the run. It seemed like he did not see much beyond where his feet were going.

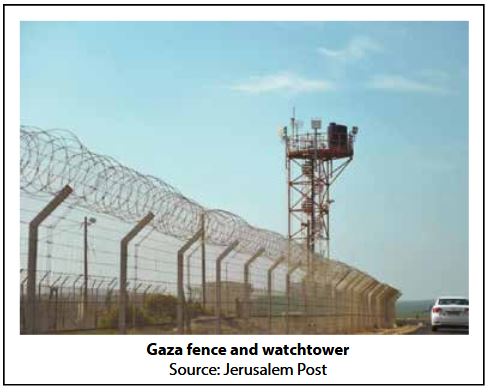

His run across the city felt less than a few minutes long. He did not notice the change of scene. The barbed wire and the fence a few hundred metres away have replaced the waves that pulled and pushed on the sand. He realized that he had been running for more than an hour because the sun was setting and the clear sky was colored in various hues of pink and red.

His heart pounded fast. He wanted to keep running to the fence, but he felt very tired. It was so quiet there that he thought he could hear his veins throbbing in his head. He looked for the watch towers. He felt very visible when in reality he was very small in the distance.

The sand stretched all around him. Fields of tomatoes and okra were growing behind him and a few houses could be seen from where he was standing. Behind the fence, an endless sea of green stood in hills that resembled the waves he had just run away from. The crashing noise came back. The large wave seemed to catch up with him again.

Ahmed started running towards the fence. This time, his run felt like a lifetime.

Historical context:

This is a story about living in Gaza with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), which affects a large number of Gazan children.

PTSD is more than the immediate experience of trauma: it is also about the incessant fear precluding any way to release it. There is no safe space, physically or spiritually, under the Israeli siege.

This story is about not finding an escape, about having a disordered perception of time, having to work as a child, having to live with pain and memories from a very young age.

It is also about the feelings of being trapped inside a physical space and not being able to escape that too.

Ahmed, the young character, is struggling with these difficulties, and physical running helps him release some of that pain. However, there is only so long a distance he is able to cross physically.

One study has found that half of Gaza’s youth aged 15-18 experience PTSD, and that the violence is exacerbated by the children’s proximity to the fighting: some two million people living in a 141 square mile area, with no safe area for escape.

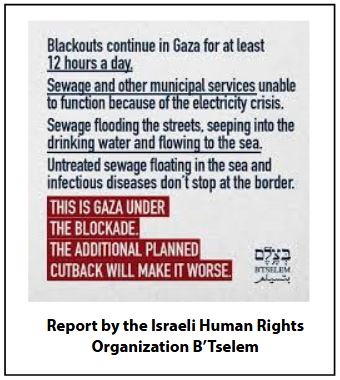

The story also explores nature as a means of escape — but also as a memory trigger. The sea being a large part of where people in Gaza go in order to find some relief, is not a source of relief any more having been polluted by years of damage to infrastructure. The restrictions on how much petrol enters Gaza (via Israel) affects how many hours of electricity sewage treatment plants get to operate. This, in turn, influences the kind of water and waste being dumped into the sea of Gaza.

For years now, large areas of he sea have been deemed too polluted to swim in. The waves in this story are of many kinds, sea waves which trigger memories of explosions and gunfire, and waves of memories, memories of loved ones and of trauma.

t h e w a i t

She drifted off to her mother’s bedroom 20 years back. A girl of 12 years old, she stared quizzically at her mother who was looking at her own pale skin in the mirror. Her mother had a bandana over her head and she had acquired a habit of pulling it over her forehead as if she was always afraid of it falling off.

“Mama, why are you sad?” she asked imploringly.

“I’m not sad, darling. I’m just tired.”

She didn’t believe her mother. It was a secret she was not supposed to know: her mother was sick. But she had no conception of the idea of death by illness. She had heard of people dying of old age, of missiles hitting their homes or cars, or of sniper bullets.

Her memory fast-forwarded to the hospital with her mother lying breathlessly on a bed. The memory suffocated her just as the room did back then with its two rows of beds. She stared at the other patients in the room as they either talked incessantly or slept heavily while their visitors talked incessantly. The pain showed on her mother’s face and she stood there watching her as her father tried to throw words of encouragement at her mother.

“Inshallah you will be ok. Just be patient and Allah will reward you.”

It all meant very little to her at the time and she still did not comprehend her mother’s fate or the true reasons that led to it.

“Um Aahed?” The doctor’s voice pulled her out of that hospital room. “Did you understand what I just told you? You needn’t worry at this point. It is still manageable if you receive the right treatment.”

His voice pierced into her temples as she stood up and walked out of the room to the hallway. There, she ran to a trashcan and threw up in it. Only when Abu Aahed put his hand on her shoulder did she

remember he was there. He handed her a tissue for her mouth and helped her wipe off some of the vomit on her scarf. Standing in the hallway, they looked into each other’s eyes as if to send each other secret messages.

“Inshallah, you will be ok.”

She was back by her mother’s bed, small and watchful. In the living room, her father was on the phone begging somebody to let him speak to an official.

“She is dying, for God’s sake,” He snapped into the microphone. “She missed her treatment six months ago. Every month, you tell me to call you the next month. We’ve been waiting for nine months now…I don’t care what is going on outside.” He screamed the last part and then she couldn’t hear him anymore.

Um Aahed, whose name was Heba before she had her first son Aahed, was starting to be aware of grown up conversations which children are not meant to be listening to. She remembered the few times she heard her mother sob behind her closed bedroom door. And she once caught her father in a similar state, sitting alone in the living room with red eyes and a tissue which he pulled to his nose and eyes every three seconds. She remembered walking to him slowly, sitting in his lap, and hugging him. It felt, at the time, that he was hanging on to her smaller body between his arms. He told her, then, that her mother was sick with a serious illness called breast cancer and that she is getting worse because they couldn’t get her treatment in time. He told her this while wiping his nose and sometimes swallowing his sobs into his chest and sometimes not being able to hold them back. She watched him silently and then ran to her room where she banged the door and started imagining the world without her mother.

It felt lonely. And she felt so sorry for her mother. She did not know what it was like to be dying like that, so slowly, at the mercy of pieces of paper. And she watched her parents go on trips to the hospital. And she saw her father get more and more angry every day. Her mother seemed quieter but she was still making time for her. It was an amazing thing to climb into her mother’s bed after a day at school and tell her about the latest adventures she had on the way to and from school.

“Today, some of the girls decided to throw stones at the boys who harassed us last week. You should have seen how scared they were. They ran off like chickens.”

“Did you throw stones with them?”

“Just small stones. The big ones were too heavy. We had to throw them pretty far.”

“Were you happy doing that?”

It took Heba a minute to think about her answer. She didn’t know which one would disappoint her mother.

“Yeah, it was fun. But I was a little bit scared because some of the boys looked big.”

“I want you to be careful. But I’m proud of you for standing up for yourself. And don’t forget to tell dad if anybody harasses you in the street again.”

It worried Heba that it was all a lie. That it was true some girls threw stones at the boys but that she was not one of those girls. She was too careful. The idea of pain and blood scared her, even when it was other people’s.

“You will be ok,” Abu Aahed repeated, holding her shoulders between his hands and gently nudging her out of her three second slumber.

His voice seeped into her heart and brought her mother’s image to her again. Unable to hold them back, she let her sobs out and buried her face in his chest, letting it absorb the shocks that burst out of her mouth.

Historical Context:

The restriction of movement has a huge role in determining people’s lives in Gaza on many levels. Sometimes this means not being able to see relatives for years and years. Sometimes, it means losing job or study opportunities abroad. Sometimes, it means losing one’s life.

Cancer treatment supplies and equipment, like most medicines and treatments, have to be let into Gaza via Israel. Since the Israeli military controls everything that comes into the Strip, Palestinians have to adhere to the military’s decisions of what Palestinians in Gaza are worthy of having.

Accordingly, cancer patients live at the mercy of military permits — be it in terms of when the chemotherapy would be available in Gaza or when the cancer patients themselves are allowed to access other kinds of therapy, e.g. radiotherapy in Jerusalem. Patients have to go outside of Gaza as radiotherapy equipment has been blocked from entering the Strip by the Israeli military for years. Patients can go to either Israel or Egypt for such treatment.

This means they have to endure a long wait in order to receive permits to cross the Erez checkpoint and be allowed into Jerusalem. This wait can take up to nine months for a response which could be an approval or denial of such permit. Many patients’ treatment has to be delayed as a result and this means that the degree of cancer becomes more severe.

Even when granted permission, the journey is very painful as patients are allowed one caretaker. This means that, for a month or more, the patient is not able to see other family members or friends, even immediate family members. Sometimes, children have been “allowed” through Erez to receive medical treatment in Israel, while their parents were blocked. But in a lot of other cases, patients are not even given a response to their ‘permit application.’

This is not new. Palestinians from Gaza have always been made dependent on Israel for all sorts of medical needs and equipment passage. Even though most of this is provided by aid and donations from other entities, it is Israel that decides when and what comes in. Therefore, this has always been an issue in Gaza, though made more severe by the more recent economic and military siege imposed as a means of collective punishment.

This story is about when a woman is told she has breast cancer. Along with the stress that cancer universally comes with, this woman has to deal with two issues: the traumatic experience of losing her mother to the same illness as a child, and the fear of having to go through the same agony and fate which her mother suffered.

This story is inspired by a real story which took place in Gaza, and is representative of thousands more.

s t a l e

The air is stale.

It’s stale everywhere, my room, the living room, the kitchen, the street, the square, the beach. Breathing is stale.

Yesterday, I lay in bed for hours, devising a plan to fix my fucked-up life. I’ve thought about selling coffee on the beach, to make a few shekels and save a few to travel somewhere where the air tastes fresh and where I could have a more decent job, maybe something related to my degree. Until then I have to buy food and contribute a small amount to the house bills. Making the profit of 30 shekels a day considering at least 20 people still want coffee from one of the one hundred moving cafes stationed all over the beach. [30 shekels is approximately $8.40 — Ed.]

I’d have to borrow a couple hundred shekels to build a decent cart and buy an initial supply of coffee and other hot beverages. So I’d be paying debt for at least seven months. And then I’d have to work another 9 or 10 months in order to save enough money to acquire a passport. After that, I’d have to sell these stupid beverages another six years at least, in order to save enough money for a border bribe. Well I could hire a boy to do the job and I could find another source of income. I don’t know… I guess I could find work somewhere, in a restaurant or as a builder. But where. This place is like a still lake. Nothing is moving.

I could borrow the money to pay the bribe and travel and then pay this person back once I got a job somewhere. What an idiot. Who would lend me this much money.

I should get out of here.

* * *

Basel walked out of his room into the hallway. The three-bedroom apartment was dark, and his father’s snoring was heard coming from the room at the end of the hallway. He went to the kitchen and poured himself a glass of water from a yellow gallon that was parked next to the sink. Standing there for a moment, he thought the whole world paused in that stillness of the night. There were very few lights outside the window. He could not place a single movement save the rising and falling of his father’s snores which were pretty harmonious with the drone that was loudly buzzing in the sky.

“I should get out of here,” he thought again and walked out of the kitchen leaving his glass next to the sink. He turned the key slowly and listened to the door screech as its hinges slowly turned against each other.

The street was deserted. “Everyone is asleep, making love, studying maybe, chatting with a lover in secret, wandering in their brains like me,” he thought as he looked up at the dark windows. Some had light inside and he wished he could go there, knock on the door and ask the person inside why they were awake, what they were doing, what was so important to keep them from sleeping. He laughed at the thought. For a moment his laughter choked him as a tear welled in his eye.

He walked, as if drunk, through his empty neighborhood. He seemed to be going nowhere as his feet carried him west. The trees arched over the street meeting from both sides to form gates of leaves which directed his way out of the city.

The waves thundered in the dark as the air stung his cheeks and nose, bringing the heavy sewage odor to his nostrils.

“When did I get here?” he asked himself, realizing that he had arrived at a dead end. The moonlit sand stretched to his left and right. The winter wind had chased everyone from the normally busy beach. Even the coffee carts were deserted. There were a few fires lit up on the corniche but they looked so vastly spread across the line that he questioned their existence.

He stood there, alone, waiting for his body to move, to turn around and go home. But it stiffened, as he stared into the waves reaching for him and pulling back into the stretching blackness in the far distance to the west.

* * *

“I don’t know, man. Turkey seems to be a good place to go.

“It’s really bad pay there, though. How long do we have to work before we can save enough money to go some place else.”

“I don’t know. A year or two.

“And then what? What do we do after that?”

“We go to Europe.”

“What for?”

“I don’t know man. Get a decent job. Have a life.”

“You’re really that naïve. You think they’re going to welcome us with open arms?”

“Why not. We both have excellent degrees. Why shouldn’t they welcome us with open arms?”

“Because we’re not European.”

“Why are you so pessimistic?”

“Look at all the ones who are already there. Dragged from one center to the other like prisoners. Fighting to be recognized as human beings. Begging to be kept in the country while working shit jobs. Can’t you see? If you don’t have money, you’re nothing.”

“That’s not true. They value humans there.”

Basel sniggered and then, repeating the words to himself, started laughing in hysteria at the proposition his friend Rami made.

“We have no value anywhere. Can’t you see? If our life is not worth a dime in our own country, where would it have value? See that drone? The person operating it has more value than you do. That criminal who is willing to kill us both, deserves a better life than we do.”

“God, man, can you hear yourself? You’re complicating things. Once we’re out of here, there will be a lot of possibilities for us.”

“I don’t think so. Whatever possibilities there are, it’s not worth all the humiliation we have to go through to get to them.”

“Yes, they are. We need a home. We need a home other than the one they’ve ruined. I can’t live here anymore man. I can’t stand it.”

“I’d rather kill myself here than go to Europe and beg to be recognized as a human.”

“You don’t have to kill yourself. Here, they will eventually kill you or you will die bit by bit just breathing this smell.”

They both laughed at that idea, sitting at a beach cafe near the port. Basel looked at the sewage pump which was vomiting brown water from under the rocks into the sea and imagined himself drowning in that water. The idea did not stir anything inside him and he momentarily felt like he was already being pushed down by the pressure of the brown sludge under the surface.

Historical Context:

The unemployment rate among young graduates reached 78% in Gaza in 2018. This is part of the economic and military siege that Israel has imposed on Gaza. It is also a result of the ongoing damage to infrastructure, such as the destruction of factories and private businesses. And it is also a result of the Palestinian political division which affects the work of civil societies in Gaza.

Along with other stressors, this affects the mental health of young people. A lot of young people seek immigration options because they do not see a livable future in Gaza. The trauma, physical danger, topped with economic difficulty all drive them to leave. But the process of leaving and finding a place to start a new life is very stressful and a lot of young people fall into mental health crises, a state of static detachment, just trying to think about it.

Stale is about that feeling of suffocation that a lot of young people have in Gaza. Because Gaza has been made what it is now, a prison, the air feels stale. It feels like Gaza has no outlets and that even the air does not move.

Even though there are strong social networks that can provide a lot of emotional support, the situation is getting worse for young people because it starts to affect their view of who they are as individuals in a conservative society, while at the same time being exposed to the rest of the world through social media.

Basel represents a large portion of young Palestinians living in Gaza. He is cynical and skeptical of any good in the world. He sees no point in emigrating to another country because he does not believe that his life will be valued anywhere in the world.

The story highlights the sea as a point of refuge, again. It is the only natural relief for Gaza’s two million inhabitants.

However, it is also another source of frustration, given it is extremely polluted, aggravating the state of mental health for young people. Even though most young people in Gaza are proactive and are continually looking for solutions, the situation is constantly getting worse and means of emotional release are becoming fewer and fewer.

Stale does not try to offer solutions to a forced economic situation. It just gives an example of how having very few choices in life can affect a young person’s view of the world.

m u s t m y o f f s p r i n g

I haven’t left my room in three days. Maybe if I starve myself, I might also starve the fetus to death.

I think of this baby growing inside me. Sometimes, I imagine it growing up in this place and cursing me for what I’ve done to it.

All my life I wondered how people bring children to the world. I asked my parents so many times why they brought me here.

“What do you mean why did we bring you to the world?” my father would say with a big smile on his face. “We were so excited when you were born. You were the light in our life. We were scared to pieces of course. Your mother, poor thing, cried when the nurse told her you were a girl.” He would laugh when he told the part about my mother crying.

My mother had a different way of avoiding my question. She would turn it into a joke, pretending that bringing me into the world was an investment project that went tragically wrong when I turned 5 and told them I wanted to be a belly dancer.

It really bothers me that they never give me a satisfying answer. I just want to hear them say that they had no choice, that I just came to their world, because it was just the way it is. I want to know how my mother really felt when she had me. I want to know what significance I had in their world and if it was really worth it bringing me here.

Anyway, it does not matter now. I’m doing the same thing. I love Raed. But I don’t think that means I want to have a child with him. What does the baby have to do with it? What will the child say in a few years’ time when it sees what kind of world I’ve brought it to? If only I can go back a couple of weeks. No, a couple of years. Unmeet Raed. Cancel his parents’ visit to see my parents. Cancel the wedding. Cancel our bedroom. Cancel sex. Cancel these fucking pills. I do love him.

“And must my offspring languish in my sight?”

I can’t shake this line out of my head. I remember when Dr. Mahmoud introduced us to Wordsworth. How enchanted I was by his words. Reading the words loudly to myself always carried me to another state of existence. It used to be so easy to pretend things were ok. To carry myself out of this place with the words. Now the words haunt me and condemn me. Must they languish in my sight?

Whatever HOPE and JOY, this child will never feel them here. Whatever I once felt in my childhood will be lost when it arrives. Once fed, loved, grown, it will realize there’s little more to do in this place.

Last year, when our neighbor’s house was bombed, and I felt my heart pounding with adrenalin, I told Raed that I never want another human to feel what I felt. I never want to be the cause of that.

In six months, I will be the cause of that, and God knows what else. This child will wonder the same things I have wondered. It will wonder why I brought it to this world, to this place.

“Alive to all a mother’s pain…”

What did Wordsworth know about mothers’ pain? I’m going to be sick…

Ya Allah. I wonder which is worse. Pregnancy sickness or this yellow seawater coming down the tap. This child will know nothing else. It will grow up with ears wired to drones and eyes adjusted to the dark rooms in the night. I can’t have this baby. I want it out.

It feels like the world is spinning. I can’t decide if it’s because I haven’t eaten in three days or because of the baby growing inside me, or both. The walls are going round and round. My feet can’t stay put anymore. I want to reach the door and call for Raed. I want him to come and catch me before I fall. I want to reach the door.

Raed is sitting by one side of my bed and my mother is sitting by the other. There is a tube going into my arm. My hair is covered. I can’t remember how they got me out of the bathroom. It feels like there is a ton of metal resting over my head. The rest of my body feels like it ran a marathon the day before. I reach for my forehead and feel a bump on it. Raed notices my movement and jumps to his feet and holds my hand.

“I was worried sick about you. Why didn’t you tell me?” He whispers then kisses me on the cheek.

My mother gets up too and starts rebuking me for being irresponsible. I look at Raed and he understands.

“Come on, Khalto. Let’s leave Samah to rest a bit. Let me buy you a coffee,” he says to my mother in a moment of silence. She agrees and he gives her his elbow to rest on while she makes her way out of the curtain surrounding my bed and the two chairs around it.

A woman pokes her head into the curtain and asks if she could come in and then does so before I make any audible response. I feel like I’ve lost the ability to speak. She sits down and says that she heard my mother lecture me. She says she’s pregnant with her second baby and that she is there because of some malnutrition complications.

“How old are you?” she asks.

I still feel unable to speak. So, I just stare at her face.

“I’m 28,” she continues, ‘I didn’t want to have this child either. My husband lost his job recently. But it’s God’s will. This child has to be born.”

I keep staring at her, wondering where she got that faith from. How she’s not afraid for the life of that baby. And as if she could hear my thoughts she responds:

“Allah will provide for the baby. There is always a way.”

But my brain is stuck on that six hundred and twentieth page of Wordsworth. “Must my offspring…”

And there my tongue moved, and my mouth said the word “Languish.”

And before I can finish the last part of the line, the air is trapped in my throat and my eyes well with tears. My fists clench over the sheets and I turn my face the other side. I feel her hand touching mine and her voice comes to me softly.

“It will be ok.”

Historical Context:

The situation in Gaza has been deteriorating since 1948. But the current siege, in which all aspects of life are deteriorating, has been going on for 12 years, the lifetime of a child born in 2007.

The fertility rate has gradually dropped over the last 20 years. This is most likely due to financial and political instability as well as introducing ways of contraceptives, albeit still not all possible options of contraceptives. Even though a lot of NGOs treat contraceptives as an important issue, it is not a priority given that the health system has more pressing issues to deal with.

In a related subject, abortion is illegal in Gaza unless the life of the mother is in danger. Doctors who perform abortions and are found out, lose their licenses and may get jailed. So, a lot of couples resort to abortion outside the health system which may or may not be successful and which puts the life of the mother in severe danger. In part, this is a story about women not having a choice in keeping or aborting a fetus.

This story is about bringing life to an unlivable place and how a woman grapples with that dilemma. In addition to the universal anxiety of brining a baby into the world at large, mothers in Gaza have the additional anxieties of economic and physical dangers. It is about the juxtaposition between family dynamics and the general situation in Gaza.

The love that Samah has for her child is so strong that she does not want it to live in such a difficult situation. She worries about its life before it arrives.

On the one hand, families can be a great form of support where the general situation in Gaza is stressful. They can be a real source of comfort and relief and children often grow up in tightly knit extended families which allows them to grow knowing they have a strong supportive network.

On the other hand, the ongoing human-caused trauma can be too much for various members in the family, especially if mental health is stigmatized in that family, as it often is in Gaza. And so, family members may feel alone because they are not able to exchange words about how they are feeling.

In this story, Samah does not only go through the trauma of witnessing a bombing of her neighbor’s house, but she also fears passing that trauma on to her baby by bringing it into the world. She is also unable to communicate with her husband or parents about being pregnant because she is still in shock and still unable to accept it.

This is also a story about children being born into the siege in Gaza and spending most of their childhoods in that confined space. Most of these children are never able to leave the Gaza Strip and so they are born into trauma and live in an ongoing traumatic setting.

In part, this story is also about guilt. Even though Samah may want to be a mother, and even though she has no control over her environment or why she has polluted water or no electricity, or bombs falling in her neighborhood, she feels like it’s her fault that her baby would have the life she has. This is partly about how the effects of colonialism can seep into the private lives and psychologies of victims.

Of course, life still goes on in Gaza and when children are born, they are loved by their parents who do all they can to provide at least healthy physical living standards for their children. Children, to our amazement, have amazing ways to find interest in their world. And Gaza’s children are no different.