By Robin Kelley

Grace Halsell is a familiar name to most readers of The Link. During the 1980s and ‘90s, her essays on the politics of Christian Zionism, the dispossession of Palestinian Christians, violence against Muslim women in Bosnia, Macedonia and Kosovo, and her illuminating portrait of Yasser Arafat, were among the most widely circulated articles to appear in these pages. As a long-time board member of Americans for Middle East Understanding, she was known as a thoughtful and committed advocate for social justice. When she passed in 2000, the entire community of activists and intellectuals dedicated to a just U.S. policy toward the Middle East mourned and celebrated Grace and the substantial body of work she left behind.

And yet, whenever I tell people—including fellow scholars—that I am writing a biography of Grace Halsell, I am greeted with blank stares. Most people have never heard of her, and the few who have vaguely recall that she wrote a book about darkening her skin and living as a black woman but confess to having never read it. How is it that an author of 13 books (including an international best-seller), a frequent guest on national television talk shows, and a widely-read journalist whose life and work provide a rich, spellbinding chronicle of the racial, sexual, and cultural temperament across America and much of the world in the second half of the 20th century, could virtually disappear?

Part of the answer, as I will show, lies in the story of how she came to AMEU in the first place. She lost her stature as a consequence of her critique of Israel, and when most of her professional contacts fled, she found unwavering allies in AMEU. It is perhaps fitting that my rediscovery of Grace Halsell and commitment to reintroducing her life and work to the world brought me to the work of AMEU and deepened my own critique of Israel’s occupation and apartheid policies. How we arrived at our respective destinations requires some explanation.

Seeking Soul Sister

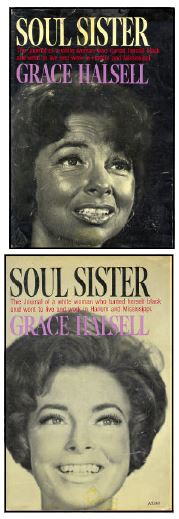

I first discovered Grace Halsell’s Soul Sister on the grimy shelf of a poorly-lit used bookstore called “Acres and Acres of Books” in downtown Long Beach, California. That summer of 1981, I was a rising sophomore at Cal State Long Beach and a newly declared History major and Black Studies minor obsessed with books about black people, race, and radicalism. Although the Halsell book was only a quarter, I almost put it back after noticing the subtitle on the tattered front cover: “The Story of a White Woman Who Turned Herself Black and went to Live and Work in Harlem and Mississippi.” Staring across from me were two pictures of the same woman—one white, bright, smiling displayed in the lower right hand corner, the other bronzed, haloed in blackness, skin shimmering from too much Vaseline, looking worried and full of trepidation. I found the dust jacket annoying. It reminded me of the army of white social scientists who invaded my community of Harlem during the 1960s and early 1970s, the do-gooders who wanted to learn about ‘soul’ and coping strategies and street-corner culture and black masculinity and change the world by changing our world.

With a year of college under my belt, I knew that whites “slumming” as African-Americans had fascinated and titillated audiences since the days of blackface minstrelsy. I knew it drew audiences to films like “Watermelon Man,” and sold books such as John Howard Griffin’s Black Like Me, which I had read in high school. But I also thought the premise was ridiculous. How can one “know” the daily lives of African-Americans after a day, a week, a year in our skin? And why did Griffin and Halsell believe they needed to actually alter their skin? As a light-skinned African American who has been mistaken for Arab, Mexican, South Asian, even Greek and Italian, I knew that all one had to do was announce he/she is “black” and few would question. Such are the absurdities of race.

No one I knew needed Griffin or Halsell or any white person to explain racial terror and state violence. I grew up in neighborhoods—in New York and California—where the police functioned like an occupying army, where young black men sitting on a curb handcuffed was a common sight. In 1981, as today, police killings and non-lethal acts of brutality were critical political issues among African Americans—a fact for which I had first-hand knowledge. By the end of that very same summer, a random assault by six white kids armed with two-by-fours and a bolt cutter put me in Long Beach Memorial Hospital. About a month later, members of the Lakewood Sheriff’s office stopped me one evening as I was running for a bus, threw me down on the wet pavement and proceeded to empty the contents of my legal briefcase on the ground—my books, papers, notebooks. They insisted I had contraband and told me that “criminals run.” As they retreated, me on the ground surrounded by my belongings, they blinded me with their vehicle spotlight and ignored my request for their badge numbers. In those moments, as tears rolled down my cheeks, neither Halsell nor Griffin could have comprehended the depths of my pain and humiliation.

I decided to buy Soul Sister because it was cheap and because stories of white flight into blackness tended to feature men. I read it once, surprised by her honesty and her efforts to address questions of sexual violence, but set it aside for the next quarter century. Then in 2008, when Barack Obama’s presidential campaign convinced pundits that America had reached a postracial age, Grace Halsell lured me back. In particular, I was struck by candidate Obama’s injunction that we should not speak about what divides us, only focus on what unites us. As he explained in his highly touted April 29, 2008 press conference on race, “when you start focusing so much on the plight of the historically oppressed . . . you lose sight of what we have in common.” In Soul Sister, Halsell found the opposite to be true: when we focus on the plight of the historically oppressed, we see even better what we have in common: our histories are bound up together, not just as a nation but also as a world. In other words, what divides us is what connects us, and our effort to resolve or address those divisions also connects us. As James Baldwin once warned white Americans, “If you don’t know my name, you don’t know your own.”

In time, I began to recognize the profundity of Halsell’s Baldwinesque quest to know the “Other” so that she might know her own self. Having just completed a big biography of jazz pianist Thelonious Monk, my curiosity about Grace Halsell could not have been timelier. I was looking for a new book project that might allow me to connect a range of global justice issues to the rise of what is often called the “American Century”—though “American Empire” is perhaps a more accurate description. I learned from a quick Google search that Soul Sister was just the tip of the iceberg. She had written over a dozen books and hundreds of articles exploring race, sexuality, war, occupation, civil rights, Latin America, Asia, U.S. immigration policy on the Mexican border, the experiences of indigenous peoples, the collapse of the Soviet Union, Christian fundamentalism and Right-wing politics, and Israel/Palestine—among other things. In other words, she explored the vital issues that had come to define the second half of the 20th century, issues about which I was most passionate.

I immediately reached out to Bob Norberg, president of AMEU and executor of Halsell’s estate, to find out if someone else was writing about her and to beg, if I had to, for the privilege of telling her story. Much to my surprise, I learned that as yet there was no biography in the works, despite the existence of two huge collections of her personal papers housed at Boston University and Texas Christian University. I was just as shocked by Norberg’s incredible kindness and generosity. Without having met me, he enthusiastically embraced my proposal, pointed me in the direction of archival sources, provided contacts for several of Grace’s surviving friends, and shared additional materials that had not been archived. I recall a strong sense of camaraderie as we discussed the Israeli raid on the MV Marvi Marmara (part of the Free Gaza Flotilla), which had occurred just weeks before I called, and the looming possibility of a second war on Gaza erupting before the year was out. Indeed, I still thank Grace for connecting me to Bob, who in turn introduced me to John Mahoney and the extraordinary work of AMEU.

In Grace Halsell I found my life’s work, the perfect subject to tell a profoundly American and global story about four forces that shaped our modern world: race, sex, war, and empire. A committed journalist thoroughly schooled in Cold War liberalism, Southern paternalism and domesticity, Grace Halsell grew distrustful of Cold War ideology and deepened her liberalism when most American liberals did just the opposite. She came to see racism as her country’s most vexing problem. As she moved from simply reporting and interpreting the world to seeking to change it, she came to believe that we needed more compassion, an empathetic world rather than more conflict and struggle. This revelation drove her to cross boundaries, enter dangerous territory in order to understand the race wars, sex wars, and imperial wars of pacification and occupation.

Seeing the World from West Texas

Grace was only five when her father began to ask questions that would introduce her to philosophy and stimulate her imagination: “Daughter, what is the mind? What is the soul? Is the mind and the soul one in the same?“ And then he might say at supper, “Were you ever on a great ocean liner?” “Can you imagine,” Grace would write later, “being in Lubbock, Texas—it’s about 300 miles from the nearest town—and thinking about an ocean liner?” These interactions with her father “created in me this desire to go beyond the ends of the world.”

Born in Lubbock, Texas, on May 23, 1923, her world typified classic mythic Americana—Anglo-Saxon, Christian, rugged frontier individualism. Her father, Harry H. Halsell, the son of a Confederate officer, lived on the range and followed his family into the cattle business, though he had lost most of his fortune by the time Grace was born. How he lost his fortune, however, counters his image as the self-made frontiersman and the paragon of American values. In 1908, 48-year-old, Harry Halsell left his wife—an heiress of a wealthy cattle-owning family—to marry fifteen-year-old Ruth Shanks. During the Depression, Grace saw her dad earn money by dismantling burned buildings and salvaging the lumber. When manual labor proved challenging (after all, he was sixty-three-years-old when Grace was born), he turned to writing classic Americana. He published several memoirs about his days herding cattle and fighting Indians, and his family’s role in settling the West Texas flatlands. His books, full of witty cowboy aphorisms blended with history and high philosophy, also reveal deep-seated sexism and racism that Grace never acknowledged.

Despite her family’s downward mobility, they always had a black housekeeper. White supremacy went unquestioned, and yet Grace was no respecter of gender conventions. She had a reputation as a tough tomboy with a sharp tongue and an even sharper pen, though by the time she reached junior high she had blossomed into a beautiful young woman who reveled in her femininity but refused female subordination. She epitomized the “New Woman” ideal of the 1930s. In 1936, she defeated all debutantes and glamour girls to take the coveted crown of Miss Lubbock. She edited her junior high school paper, Cowboy World, and then took over Lubbock High School’s Westerner World, for which she won the state’s top awards. Her prize-winning editorial, published in 1940, excoriated France for focusing more on building and fortifying the Maginot Line instead of inculcating “loyalty,” “honesty,” and “real values” that might have prepared the population to resist a German invasion. The teenaged Halsell worried that this might be the fate of the U.S. if we ignore the moral, ethical, cultural elements of our national identity in our quest for military supremacy. She did not reject military supremacy; rather, she argued that the key to American defense was inculcating and spreading American values. Interestingly, Henry Luce’s widely read essay, “The American Century,” appeared in Life magazine just a few months later rejecting isolationism and praising American values as the bulwark against fascism and the foundation for American hegemony.

In 1941, even before she graduated, she landed a job at the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. For two years, she wrote for the paper while attending nearby Texas Tech College, and then in 1943 joined her older sister in New York City. To most Texans in the 1940s, New York was sin city, a strange melting pot of mongrelization, outspoken Negroes, Reds and red-light districts. New York was 52nd Street, Greenwich Village, Harlem (which exploded in a major riot about the time she arrived). Communists were elected to public office because of proportional representation. Drugs had become a public menace, prompting the LaGuardia Commission to issue its controversial 1944 report. The city’s campaign to uproot Times Square’s thriving sex industry had just gotten underway. This is what New York looked like when Grace began working in the reference department at the New York Times and taking extension courses at Columbia University in politics, history, and anthropology. The city opened her up to a diversity of people and proved to be the catalyst for her subsequent career as a globetrotting journalist.

She returned to Texas immediately after the war and accepted a job with the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, continuing her studies at Texas Christian University. Then in 1948, she did what all prospective parents of the baby boomer generation were supposed to do: she got married. Her husband, a local police detective named Andre Fournier, was fifteen years her senior. They owned a modest home, went to church on Sunday, and were supposed to disappear in the lonely crowd of loyal, law-abiding, patriotic Americans. Instead, Grace found herself living the life Betty Freidan described in her classic The Feminine Mystique, or that Richard Yates rendered in Revolutionary Road. Their marriage was troubled from the start. Fournier was possessive, jealous, and even violent, and Grace increasingly found the Lone Star state a bit too small and provincial. She made a couple of brief trips abroad during their four-year marriage, but in 1952 she filed for divorce and settled in Europe for a year, traveling between Germany, Italy, France, Yugoslavia, Spain, Brussels, Switzerland, Austria, Greece, Turkey, and Algeria. She sold special interest stories to Texas papers about Texans in Europe, but much of what she saw and documented is the American Cold War for hearts and minds, for bases and oil fields, for consumers. And as one of a handful of women correspondents, she experienced first-hand the consequences of transgressing Cold War gender and sexual conventions. While based in a West German militarized zone in 1952, she rebuffed a Public Relations officer who had sexually harassed her. He retaliated by having her base pass revoked and dispatching military police to her apartment in the middle of the night. Incensed, she exposed the incident in an op-ed piece for the Houston Chronicle (Feb. 2, 1953), “Have We a Military Goon Squad Abroad?”

Halsell’s criticisms, however muted, exposed the link between militarism and the subordination of women, though she remained uncritical of America’s Cold War cultural project abroad. Her perspective began to change when she covered North Africa and Asia in 1955-56. Her columns as well as diaries, recollections, and correspondence, paint a portrait of societies fearful of losing sovereignty and cultural autonomy under American hegemony, intrigued by modernization and the promise of economic growth, and yet skeptical of Cold War militarization undergirded by atomic weapons.

Just consider the world she is seeing: Egypt under Nasser just after the Suez crisis and seven years after the creation of Israel; Malaysia consumed by a guerrilla war; Taiwan and Hong Kong emerging as outposts for the war on Communist China. She is there as the CIA is launching a wave of secret covert actions to overthrow Mao Zedong, and evidence suggests she had an inside track on some of the military operations in the “Far East.” Halsell, in other words, left behind a unique perspective on the cultural and military operations of the Cold War and how they were connected.

In 1956, she returned to Texas to take a position as editor of a trade magazine published by the Texas-based Champlin Oil and Refinery, at the very moment when U.S. corporations were waging a campaign for dominance in the global petroleum industry. In less than three years, Halsell had had enough. She quit her job and with money saved moved to Lima, Peru where, during the four years she lived there, she wrote an English-language column for La Prensa, Lima’s daily paper.

Once again, Grace just happened to land in the hottest zone of the Cold War—Latin America at the birth of the Cuban Revolution. Her daily dispatches, her experiences, her personal encounters, her photographs, even the children’s books she wrote about the history and geography of Peru, Colombia, Guatemala, and Honduras, give us a unique window on U.S. influence. These books, written to explain to American children the politics and culture of our “neighbors,” promoted the U.S. imperial project. On the one hand, Halsell emphasized the kind of cultural relativism she learned at Columbia University—i.e., we need to respect differences between cultures. On the other hand, she repeated the official narrative that the U.S. military had to intervene in Guatemala in 1954 to save the people from communism—not to protect the United Fruit Company for nationalization.

From Mekong to Mississippi

Whatever criticisms Halsell may have had of U.S. Cold War politics remained muted until 1965, when she became one of the first women journalists to report from Vietnam. She saw Vietnam for what it was—a colonial war. Witnessing the large number of children and women killed or hospitalized by U.S. bombs profoundly affected her. “How, I wondered,” she later recounted in The Illegals, “can we do this to people? And I knew: We can do it because we do not see them. We make them invisible.” Grace not only exposed the human suffering brought on by U.S. operations, but she reflected the deep divisions the war generated among Americans. Vietnam became the touchstone for conflicts over patriotism, U.S. foreign policy, free speech, and the rise of the counterculture. And just as these domestic battles began to heat up, Halsell landed a job in the seat of American power.

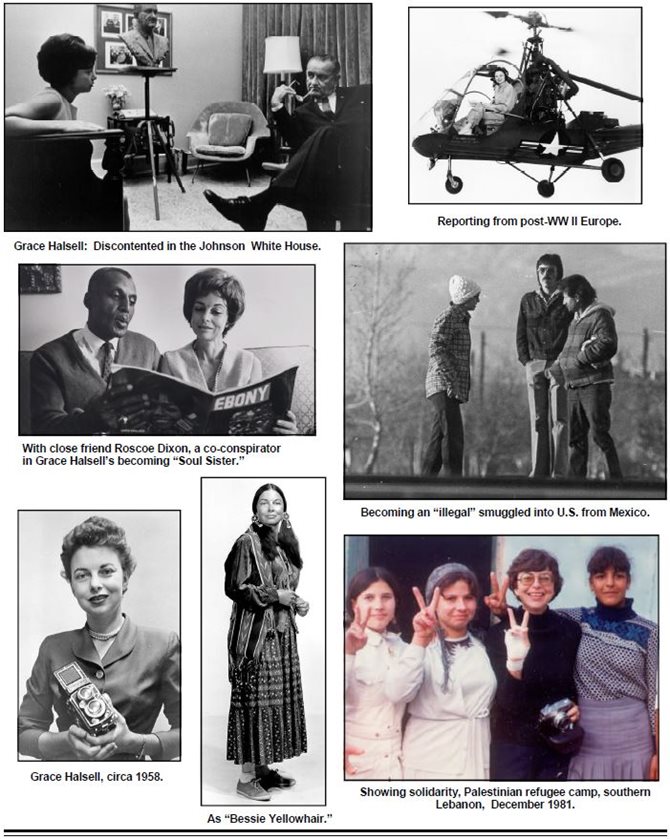

Soon after returning from Vietnam, the Houston Post appointed Halsell to be their Washington correspondent. Almost immediately, President Lyndon Baines Johnson noticed her among the press corps and, as was his custom, personally approached her with an offer to work directly under him as his secretary. Anyone who knew Johnson wasn’t surprised by his sudden interest in Grace. She was attractive, well-dressed, smart, and he liked to surround himself with “pretty women secretaries,” for sexual favors and because he enjoyed the spectacle. With eyes wide open, she accepted a post on Johnson’s staff, though she made it clear that she would be no one’s secretary.

Although she escaped LBJ’s entourage, she was constantly called on for private meetings, and did little more than polish messages and speeches. She found the job boring and the working environment intolerable. Her immediate boss from October 1965 to April 1966 was James H. Moyers, brother of Bill Moyers. Jim Moyers never disguised his contempt for Halsell, and the hostility she faced from fellow staffers dominates her FBI file. She was accused of being overly ambitious, of delegating her tasks to others, leaking information to the press, and devoting much of her office time to her own personal writing. But the most damning accusation was that she was “brazen and aggressive with men.” She was described as little more than a smart jezebel, using her sexual wiles to gain influence and keep her job. Even staff members who did not work with her directly found her behavior disgraceful. Eventually, Moyers had her transferred to the office of Paul Popple, Assistant to the President, where she spent months answering Johnson’s mail.

Rumors of Grace Halsell’s promiscuity and hypnotic sexual charms are greatly exaggerated. Her real crime was that she stood up to her male co-workers, went over her immediate superiors heads by taking advantage of her access to the Oval Office, labored as little as possible on White House business, and instead spent many hours locked in her office working on her own projects. As a rare female employee, a confidante, and an imaginative writer, her experiences in the White House revealed the nexus between gender and power and the subjugation of women. And it was on this difficult ground of gender oppression, amidst an increasingly visible and severe racial crisis, that she found her way to writing Soul Sister.

In the aftermath of Dr. King’s assassination in 1968, she discovered John Howard Griffin’s book, Black Like Me. Halsell wanted to do what Griffin did: darken her skin without changing the markers of her identity—her education, training, name, and culture. But unlike Griffin, who limited his experiment to the South, she decided to begin her journey in Harlem, where she feigns her own ignorance, expressing the kinds of fears and stereotypes about Harlem held by much of white America in 1968. Withholding the fact that she had visited Harlem before, she wrote: “I have never seen it except in a cluttered, symbol-ridden mind’s eye. I’ve read the papers, heard the reports of violence in the streets,” knew about the drug addicts, the murderers, the rapists, and even the notorious Black Panthers and “those who want to kill a white for every black that’s ever been killed.”

Once she prepares the reader, she then pulls the proverbial wool from her eyes, revealing a complex, diverse, friendlier Harlem full of colorful and non-threatening personalities. The people of Harlem come across as incredibly generous and thoughtful. Likewise, when she arrives in Mississippi, it is the Civil Rights activists—fully aware of what she is doing, who risk their own lives to keep her safe. By the end of the book, we discover along with Grace that she was far less likely to become a victim of sexual violence on a dark Harlem street than in the privileged home of a white Mississippian.

She set out to show white people “how much alike we all are,” but ended launching the first in a series of exposés about white supremacy, our nation’s blindness to institutionalized racism and its effect on the entire country. Indeed, in her quest to find the authentic black experience, she discovered whiteness: “I had only to imagine myself black and then, for the first time, I saw myself white!” She was reminded of her whiteness when a huge number of African Americans, especially women, waged war on Soul Sister. They accused Halsell of profiting off of black misery and falsely claiming to understand black women by pretending to be one. Besides hate mail and hostile reviews in the black press, Halsell was the target of protesters who picketed Ebony magazine’s offices after it ran a December 1969 feature about Soul Sister and its author. The attacks hurt Grace. But rather than run from this highly controversial subject, her obsession with black/white race relations only deepened.

Sex and the Single Girl . . . From

Plantation to Reservation

With the publication of Soul Sister, Halsell reached the pinnacle of fame and financial gain. She would never again make this kind of money. Still, she was terribly unhappy and unhealthy. She returned from Mississippi a complete wreck, exhausted and broken from her experiences, ill from a nasty case of Hepatitis B, and depressed from the unrelenting criticism she received from black readers. Meanwhile, she agreed to collaborate with Mississippi political activist Charles Evers—brother of Medgar Evers—on his memoir and used her spare time to research a project her editor loved: a book, not surprisingly, about sex across the color line.

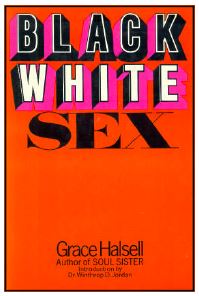

Black/White Sex, published in 1972, arguably represents one of the first in a wave of popular books on sex sensitive to women and their desires. It appeared a year before Erica Jong’s best-selling Fear of Flying and Nancy Friday’s, My Secret Garden: Women’s Sexual Fantasies, and it preceded Shere Hite’s Sexual Honesty, by Women, For Woman (1974) and The Hite Report on Female Sexuality (1976). Although Black/White Sex shares much in common with these texts, Halsell puts race at the center, thereby ensuring its absence from the best-seller list. By the early 1970s, a growing number of Americans grew tired of racial issues, and the new sex books operated on the premise that “women” were white and their sexual frustrations personal, not social or political.

Halsell’s objectives were loftier, even radical: to expose and uproot racial myths about sexuality, such as white men’s fears and fascination with black men’s penis size and black women’s insatiable sexual appetite, or the contrasting dominant image of the white woman as virginal, pure, even frigid. She lays her cards on the table right away, noting that as a Southern white woman she is aware of “the white man’s wish to ‘protect’ the ‘purity’ he believes embedded in whiteness, and I know, too, of the black man’s hunger to possess a white woman, for reasons that go beyond mere lust.” And in the guise of a black woman, “I realized that the white man desired me, not in spite of but because of my blackness.” She wanted to obliterate the racial/sexual myths she documents while making the case that women’s liberation and gender equality, and black liberation and racial equality, are necessary for transforming society and our sexual relationships.

Sex and freedom had long been her obsession, but by the early 1970s, Second Wave Feminism had irrevocably shaped her thinking, despite her own misgivings about women’s liberation. As she was finishing the final draft of Black/White Sex, she proposed a book that was part memoir, part critique of liberal feminism’s failure to embrace a politic of love, sex and joy. She promised her editor, Martin Levin, “an uninhibited, often joyous account of a woman taking in huge draughts of life and sex without pausing to survey the social consequences or toting up the wins and losses.” She began drafting the book, but he wasn’t interested. Instead, she returned to racial masquerade, this time living as a Navajo.

Halsell was initially reluctant to take up American Indian issues, and she seemed woefully ignorant of the political tremors erupting on the reservations. In 1969, her brother, Ed, had taken a job as an attorney for the Navajo tribe in Window Rock, Arizona, and persuaded Grace to visit. At first she was nonplussed, convinced that black oppression was infinitely worse since Indians could “pass” after leaving the reservation, whereas black people can never escape their skin. But then Ed suggested that Indians might possess a philosophical outlook fundamentally different from the militarism and racism Grace had vociferously critiqued. “With our cruel wars,” he wondered aloud, “one must ask: was not the ‘uncivilized’ way of the Navajos more peaceful and in this respect more ‘civilized’ than our own?”

Sold on the idea, Grace went to Arizona, lived with a Navajo family, submitted to the teaching of tribal elders, and was then allowed to “borrow” another woman’s identity to live temporarily as a Navajo woman in the white world. The point of her journey, as chronicled in her book Bessie Yellowhair, was two-fold: to introduce readers to Navajo culture, lifestyle, and philosophy, and to expose the racism Indians endure off the reservation. She was impressed with the Navajo’s approach to ecology and living in harmony with the environment, traditional systems of governance, and their application of compensatory justice.

She also harbored certain stereotypes. She believed that to pass for black required little more than darkening her skin since, in her view, blacks and whites were essentially the same. But living as a Navajo required months of “training” and a fundamental cultural and psychological shift. “Being an Indian,” she wrote, “is not having a certain skin color. It is not anything on the outside. It is the desire to live close to ‘Mother Nature,’ to be in harmony with the sky and earth and plants.”

By perceiving American Indians as anti- or pre-modern people, she completely missed the contemporary political movement. She believed that the authentic Indian was not interested in politics, rights, or power, and at no point did she acknowledge the American Indian Movement, the occupation of Alcatraz Island, or the “Trail of Broken Treaties March.” On the eve of Bessie Yellowhair’s release, she wrote to Robert Williams, a friend: “the sad plight of Indians is that they can never ‘win’—if they become militant and get their ‘rights’ then they are like others, and no longer are Indians.”

On the other hand, her journey to Navajo country commenced a longstanding friendship with the eminent Indian historian and activist Vine Deloria. Their correspondence reveals a deep mutual respect, as well as a teacher-pupil relationship in which Deloria attempts to relieve her of certain myths about Indian history. Although she never returns to writing about indigenous people, Deloria planted the seeds for a critique of settler colonialism, which, I suspect, profoundly shaped her thinking about Israel a few years later.

Crossing the Line

During the 1970s, the U.S. border with Mexico had become increasingly militarized as a result of both beefed up patrols as well as a proliferation of armed vigilante groups. In August of 1976, white ranchers in southern Arizona kidnapped, tortured, and robbed three undocumented Mexican migrants—a gruesome crime for which no one was convicted. The recession, high unemployment, militant campaigns led by the United Farm Workers, and a general wave of anti-immigrant sentiment exacerbated tensions on the border and undermined any serious efforts at immigration reform.

It was under these conditions that Grace, now fifty-four-years-old, chose to experience life as an undocumented Mexican laborer. She worked in the fields harvesting crops in New York and California, interviewed scores of immigrants in jails, prisons, and detention centers, and illegally crossed the Rio Grande with fellow immigrants at least three times. The result was The Illegals, her most radical, most prescient book to date. While she described some harrowing moments crossing the border, the book is shorn of the personal crises of identity and confessionals that had characterized her earlier work. She returns to reporting, pays less attention to her own experiences and focuses instead on the immigrants themselves, the border patrol, as well as labor organizers and activists in the Sanctuary movement. Even then, the system was unsustainable—the U.S. was spending $250 million a year to fight a war to staunch the flow of undocumented workers and slowly creating a police state in the Southwest. The cost of locking up undocumented workers then was about $8,000 a year in prison costs alone, when Mexican farmer workers were earning less than $75 a year.

The Illegals, although not the best-seller her publisher hoped for, received favorable reviews, garnered her a major op-ed in the New York Times, and House and Senate members on both sides of the aisle took notice—though it is not entirely clear how the book affected immigration debates. What is clear, however, is that on the eve of Ronald Reagan’s election, as the country shifted further to the right, Halsell’s work became increasingly politicized and controversial. This was not her intention. She considered herself a popular writer who sold special interest stories. She survived on royalties and speaking fees, and her penchant for traveling and the growing needs of her aging mother drained her finances. Her plan to write a book chronicling a solo journey across Antarctica fell through, in part because the editor wanted a memoir emphasizing the “man-woman theme,” either focusing on her sexual relationships or the challenges of maintaining a career without losing one’s femininity. She did begin a book tentatively titled “Loving Men,” but nothing came of it. Instead, she turned her attention to religion.

Christianity had long been an essential facet of her life, having played a formative role in her upbringing. But by the 1970s, with the rise of Christian fundamentalism and its growing political influence, it had become an obsession. As early as 1973, she proposed a book on Oral Roberts and the evangelical movement, in which she would enroll in his school and “learn at firsthand how one becomes a faith healer and performs miracles.” The publishers she approached were lukewarm, and Halsell herself balked because, as she wrote to Levin and others, she found most evangelicals to be “so racist.” A few years later, she came up with another aborted idea: a travel book tracing Apostle Paul’s 12,000 mile trek through the Roman Empire, to be in bookstores by Christmas.

In 1979, she finally settled on a trip to the Holy Land, envisioning a popular travel account of three faiths negotiating strife-torn Israel/Palestine. She planned to live with various families in Jerusalem and the West Bank—Israeli settlers, Palestinian Muslims and Christians, and Mizrahi Jews. Macmillan bought the book on the presumption that it was not to be political. Rather, as she explained to her editor, Henry William Griffin, her objective “as was the case in Soul Sister [is] to establish that one can go on a journey with empathy for all.”

Her editor, agent, publicist and critics were not so keen on “empathy for all,” if it meant criticizing Israeli occupation. The correspondence between her and Griffin over the book’s content reveals yet another stage in Grace Halsell’s education. She finally had to come to terms with what a politics of empathy requires—it means taking sides. It means political stances are unavoidable. She sought out all sides, using her friendship with her former lover and trainer—an Egyptian named Mourad Khamildn–to make contacts with Palestinian activists. She sought out P.L.O. members in Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon, read reports issued by the Palestine Human Rights Campaign, met with Jewish critics of the regime such as Israel Shahak, and documented unrelenting state violence, inhumane conditions of the refugee camps, arrests, and state-sponsored terror attacks on Palestinian elected officials (including Palestinian mayors of Nablus, Hebron, Ramallah, and El-Bira), as well as the outright theft of Palestinian land, homes, water, and electricity. And if this wasn’t enough, she almost died at the hands of a rifle-wielding Israeli soldier during an assault on Birzeit University in Ramallah.

The experience changed her life. Soon after returning from the West Bank, she penned a long letter to Griffin in which she clearly blamed racism for the subjugation of the Palestinians. “In Vietnam I visited hospitals and saw women and children without arms and without legs and we did not care that we had bombed them because they were people of color and we did not see them. Like the blacks a few years back they were invisible. And in the West Bank so it is with the Palestinians. They are tortured and we do not care because they are orientals and we do not see them.” She held U.S. Cold War policies partly responsible, noting that thanks to American support Israel has “the fourth largest arsenal of weapons in the world . . . [and] has consistently cooperated with repressive regimes in Latin America, Asia, and Africa.” One reader of her manuscript, Colin Williams, insisted that she “make allowances for fear-produced fantasy [of the Palestinians]” since “the stories of torture, etc., are sometimes over-stated and unreliable.”

Henry William Griffin, her editor, found her treatment of Jews flawed, insisted that she open the book with Judaism rather than Islam, and suggested that she refrain from criticizing Israel. He rejected her original title, “Journey to the Land of the Palestinians,” and asked her to emphasize “the irony of three God-fearing faiths fighting for survival on the West Bank.” Halsell did her best to accommodate these criticisms, but she also pushed back, arguing in a letter to Griffin that “I am not writing about faiths as such or religion as such but people, people who are crying and killing and bleeding—it is a book of politics in a land that we by tradition call holy.”

In the end, Macmillan honored their agreement to publish the book (now titled Journey to Jerusalem) but did nothing to promote it. Her editor was either forced to resign or fired just as the book was about to go to press, and Halsell’s long-time, agent John Hochman, left her as soon as he saw early drafts of Journey. She also lost important friendships, most notable being the indomitable Iphigene Ochs Sulzberger, whose father, husband, and son had run the New York Times since 1896. Iphigene and Grace had kept up a lively decade-long correspondence that ended in what would become a fierce disagreement over Halsell’s criticisms of Israel. (The letters and conversations about Israel are so stunning that Halsell had gathered them together with the intention of publishing a small book about “the sudden, irreconcilable demise of that friendship.’) Journey to Jerusalem effectively ended her career as a commercial writer.

By some accounts, Grace Halsell appears to have reached rock bottom. Lucrative speaking engagements disappeared, she went through several incompetent or unscrupulous agents, editors at the major trade presses ceased taking her calls, and all the while her relationship with her siblings frayed over their mother’s health and property. On the other hand, Grace’s experience with Journey and her new friendships with Arab, Muslim, and Palestinian solidarity activists seemed to energize her. She began writing essays on Middle East issues in various journals and magazines, became an active presence in AMEU, and deepened her investigations into the link between Christian Zionism and Israel.

In what would become her final masquerade, she passed as the person she was probably supposed to have become—a right-wing Christian fundamentalist—and traveled to Israel with Jerry Falwell’s “Moral Majority” in order to examine the Christian Right’s embrace of Armageddon or “new dispensationalism.” She joined hundreds of Christian “pilgrims” who visited Israel in order to see where God’s final reckoning would take place, according to their interpretation of scripture. They believed that God gave the Jews the Holy Land temporarily, and that the coming war would result in the destruction of all who are not saved and God would take back the land for the true believers. Halsell cautioned against dismissing these ideas as the ravings of a lunatic fringe. Her book, Prophecy and Politics: Militant Evangelists on the Road to Nuclear War (1986) demonstrates that evangelical leaders have not only pushed Israel to deploy its nuclear arsenal as the first salvo in the destruction of the world as we know it, but that “new dispensationalist” ideas have influenced the higher echelons of government—from President Ronald Reagan to conservative members of Congress.

Despite having lost the popular perch she enjoyed in the early 1970s, Halsell’s work became increasingly political and took on a greater tone of urgency. She wrote about international human rights violations, warned of the dangers of right-wing fundamentalism, and planned several other books that never saw the light of day—including a book about the impact of the Cold War on everyday life in the Soviet Union. She did finally complete her memoirs, In Their Shoes, published in 1996, but it fell short of capturing the profundity and expanse of her life. I suspect the book was written in haste because a year before its release she was diagnosed with multiple myeloma cancer probably caused by the drugs she had taken to darken her skin for Soul Sister.

In the final months of her life she turned to her own cancer, her pain and ravaged body. She never produced more than some detailed notes and a working outline for what a book might look like, but by this time she knew her time was short and her body began to fail her. She died on August 16, 2000—a month before Palestine’s Second Intifada.

My Journey to Jerusalem

I am still searching for Grace Halsell, whose truths and fears, lives and loves lay fragmented in a vast sea of archival boxes awaiting reconstruction. As I work through the pieces of her life I am reminded of the considerable impact Grace has had on me—my ideas, my understanding of history, even my politics. She demonstrated why empathy is an essential ingredient of any just, transformative politics. Like James Baldwin, she reminded me that walking in the shoes of others is a pathway to know oneself. She opened up an alternative history of race and sex, revealing an intimate side of the American Century. Race and sex are taboo and dangerous, yet so intimate and fundamental to who we are as modern human beings in a diverse, democratic universe that they reside at the fulcrum of human freedom and social hierarchy. For some people, race is a burden; for others it is a privilege. The same can be said for sex: the “second sex,” in the words of Simone de Beauvoir, spoke to an oppressive place striving to become free, autonomous, and powerful.

But above all, my search for Grace led me directly to Palestine. When the U.S. Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (USACBI) invited me to be part of a delegation to the West Bank in January of 2012, I saw it as an opportunity to interview people who knew Grace. While I found several of her friends and acquaintances willing to share memories of her, what I witnessed fundamentally changed my life. The checkpoints, the separation wall, the crumbling, half-constructed buildings, the fatigue-clad, heavily armed kids checking IDs, the freshly paved settler roads, the ever-expanding Jewish settlements rising from hilltops laying siege on Palestinian villages below—I’d seen it before in books, articles, on YouTube. But now the “facts on the ground” were real, elbowing my heart, burning my eyes. We heard testimony from Palestinian families forced out of their homes in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem, saw Palestinian merchants in Hebron endure a daily barrage of bricks and garbage from ultra-Orthodox settlers intent on driving them out—a Palestinian city where nearly 2,000 IDF troops are deployed to protect about 500 Jewish settlers who terrorize the indigenous inhabitants with impunity.

I thought about how Grace Halsell experienced these streets, and how much they had changed after three decades, the failure of Oslo, the Second Intifada, the expansion of settlements, and Israel’s extraordinary efforts to project itself as a “normal,” modern democracy. It was unnerving to cross the highly militarized zone dividing Ramallah from East Jerusalem, and minutes later stroll around Hebrew University’s Mount Scopus campus, with its state-of-the-art library and computer center, its lovely hilltop view, its high-end cafes where students and faculty can read, chat, and simulate normal university life. The embattled Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood, a mere twenty-minutes by foot, felt like another country.

Israel’s normalization project works so long as Palestinians and their life conditions remain invisible, contained, and the rest of the world remains silent. Grace Halsell’s life and work prove that silence has never been an option, and telling the truth about injustice shatters any semblance of neutrality. Most of us know now what Grace had figured out over three decades ago: that the greates

t threat to Israel’s apartheid system is not the ugliness of violence, containment, and dispossession, but the beauty of struggle. Everywhere—in the refugee camps, at the universities, schools, and community centers, young Palestinian women, men, and children are waging a non-violent, creative movement to build a new, democratic, inclusive nation, free of occupation, free of second-class citizenship. It took Grace years of putting her body and her career on the line to comprehend the enormity of subjugation and the resilience of people confronted with racial and sexual violence, economic exploitation, and social deprivation. Palestine was her turning point, her moment of truth when empathy became solidarity. Yes, she paid a dear price for her stand, but she was willing to pay it because she knew she was on the right side of history. ■